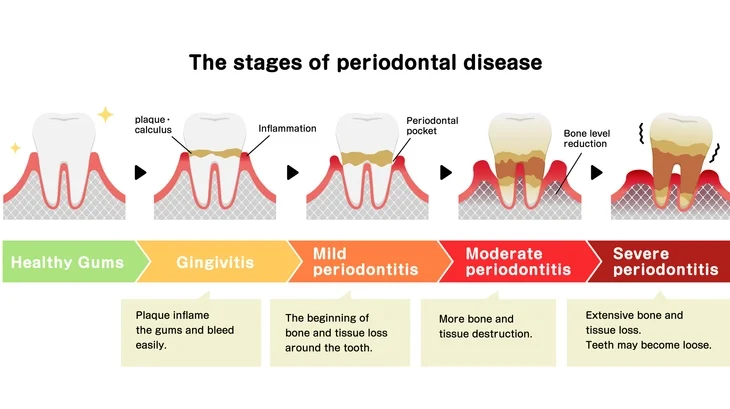

Periodontal diseases are among the most common oral health problems affecting people worldwide. They involve the inflammation and destruction of the supporting structures of the teeth, including the gingiva (gums), periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. The severity of periodontal disease can range from mild, reversible gingivitis to severe periodontitis that can lead to tooth loss and systemic health implications.

As our understanding of the pathophysiology, microbial causes, and systemic connections of periodontal diseases has evolved, so too has the need to classify them accurately. Classification systems are essential for diagnosis, communication, treatment planning, and research. They allow clinicians to describe the type, severity, and progression of disease clearly and consistently.

Two major international workshops — held in 1999 and 2017 — established the most widely recognized classification systems for periodontal diseases. While the 1999 system served as the standard for almost two decades, rapid advancements in periodontal research prompted the creation of a more comprehensive and flexible framework in 2017.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Need for Classification

Before delving into the specific classifications, it is important to understand why classification is necessary in periodontology. Periodontal diseases vary greatly in cause, severity, and rate of progression. Without a systematic classification:

- Clinicians would struggle to communicate about cases effectively.

- Treatment plans could become inconsistent or inappropriate.

- Research comparisons would be unreliable due to differing definitions.

- Early diagnosis of systemic-related periodontal conditions could be missed.

Therefore, a classification system must reflect the etiology (cause), pathogenesis (disease process), clinical presentation, and response to treatment of different periodontal conditions.

The 1999 Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions

The 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions was a landmark event that created a comprehensive framework for diagnosing and describing periodontal diseases. It was widely adopted in clinical practice and education until 2017.

The classification divided periodontal diseases into eight major categories, summarized below.

I. Gingival Diseases

Gingival diseases were divided into two main groups: plaque-induced and non–plaque-induced.

A. Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases

These are the most common forms of gingivitis, caused by dental plaque accumulation along the gingival margin. The plaque biofilm provokes an inflammatory response in the gums, leading to redness, swelling, and bleeding on brushing.

Plaque-induced gingivitis was further subdivided based on contributing factors:

- Gingivitis associated with plaque only: May occur with or without local contributing factors such as calculus or faulty restorations.

- Gingival diseases modified by systemic factors: Systemic conditions such as puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, or diabetes can alter the inflammatory response to plaque, leading to more severe gingivitis.

- Gingival diseases modified by medications: Certain drugs like phenytoin, cyclosporin, and calcium channel blockers can cause gingival enlargement. Oral contraceptives may also exacerbate gingival inflammation.

- Gingival diseases modified by malnutrition: Nutritional deficiencies, especially vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) or protein-energy malnutrition, can contribute to gingival inflammation.

B. Non–Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases

These are less common and result from infections, allergic reactions, or trauma rather than plaque accumulation. Examples include:

- Specific bacterial infections (e.g., Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Treponema pallidum).

- Viral infections (e.g., Herpes simplex virus).

- Fungal infections (e.g., Candida albicans).

- Genetic conditions (e.g., hereditary gingival fibromatosis).

- Allergic reactions or foreign body responses (e.g., to dental materials).

II. Chronic Periodontitis

This is the most prevalent form of periodontitis in adults. It involves the slow progression of attachment loss and bone destruction due to prolonged plaque accumulation.

Chronic periodontitis can be localized (affecting <30% of sites) or generalized (affecting ≥30% of sites).

Severity is classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on clinical attachment loss and bone loss.

III. Aggressive Periodontitis

Aggressive periodontitis occurs in otherwise healthy individuals and is characterized by rapid attachment loss and bone destruction. It often affects younger patients and may have a strong genetic component.

It is divided into:

- Localized aggressive periodontitis (often affecting first molars and incisors).

- Generalized aggressive periodontitis (affecting multiple teeth beyond the first molar-incisor pattern).

IV. Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Disease

Certain systemic conditions can predispose individuals to periodontitis or worsen its progression. Examples include:

- Hematologic disorders (e.g., leukemia).

- Genetic disorders (e.g., Down syndrome, Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome).

V. Necrotizing Periodontal Diseases

Necrotizing diseases are acute infections associated with compromised immune response, malnutrition, or poor oral hygiene.

They include:

- Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG)

- Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP)

Patients typically present with pain, bleeding, ulceration, and a characteristic “punched-out” appearance of the interdental papillae.

VI. Abscesses of the Periodontium

These are localized purulent infections within the gingival or periodontal tissues. They can occur as gingival abscesses, periodontal abscesses, or pericoronal abscesses, often resulting from obstruction of periodontal pockets or foreign bodies.

VII. Periodontitis Associated with Endodontic Lesions

This category covers conditions where periodontal and endodontic (pulpal) infections coexist, such as combined endo-perio lesions.

VIII. Developmental or Acquired Deformities and Conditions

This includes:

- Gingival recession.

- Tooth anatomical anomalies.

- Mucogingival deformities.

- Occlusal trauma.

- Tooth or prosthesis-related factors contributing to disease.

Limitations of the 1999 Classification

Although comprehensive, the 1999 classification had several limitations that became more apparent with time:

- Ambiguity between chronic and aggressive periodontitis:

Many cases did not fit neatly into one category, leading to inconsistent diagnoses. - Lack of recognition of disease progression and stability:

The system did not consider whether the disease was currently active or stable after treatment. - Limited inclusion of systemic and genetic factors:

With growing evidence linking periodontal disease to systemic health (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease), the classification needed to reflect this. - Inadequate coverage of peri-implant diseases:

Implants had become common by the 2000s, yet the 1999 system did not provide a detailed classification for peri-implant conditions.

These issues motivated the development of a more modern and flexible classification system.

The 2017 Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions

In November 2017, the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) collaborated to create a new framework reflecting current scientific understanding. The results were presented at EuroPerio9 (2018) and published as the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions.

This updated system emphasizes periodontal health, disease staging, and grading — similar to how other chronic diseases (like cancer or diabetes) are classified. It also provides detailed recognition of peri-implant diseases, acknowledging the rise in implant therapy.

I. Periodontal Health, Gingival Diseases, and Conditions

This category includes:

1. Periodontal and Gingival Health

- Describes healthy periodontium with no attachment loss, inflammation, or bleeding on probing.

- Can occur in intact or reduced periodontium (for example, after successful therapy).

2. Gingivitis – Dental Biofilm-Induced

- Inflammation confined to the gingiva, caused by plaque accumulation.

- Reversible with proper oral hygiene.

3. Gingival Diseases – Non–Dental Biofilm-Induced

- Lesions not caused by plaque, including genetic, neoplastic, or traumatic lesions, and those caused by infections or systemic conditions.

II. Periodontitis

The 2017 classification introduced staging and grading for periodontitis, marking a major evolution in diagnostic methodology.

Staging

- Reflects the severity and extent of the disease based on clinical attachment loss, radiographic bone loss, and tooth loss due to periodontitis.

- Stages range from Stage I (initial) to Stage IV (severe with potential tooth loss or masticatory dysfunction).

Grading

- Describes the rate of progression and considers risk factors such as smoking and diabetes.

- Grades range from Grade A (slow progression) to Grade C (rapid progression).

Subcategories of Periodontitis

- Necrotizing Periodontal Diseases – similar to NUG/NUP, but updated terminology.

- Periodontitis – replaces “chronic” and “aggressive,” unifying them into one entity with variable presentations.

- Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Disease – recognizes systemic disorders directly influencing the periodontium.

III. Other Conditions Affecting the Periodontium

These include a variety of conditions not primarily caused by bacterial plaque but still affecting periodontal tissues:

- Systemic Diseases or Conditions Affecting Supporting Tissues

(e.g., immunological disorders, genetic connective tissue diseases). - Periodontal Abscesses and Endodontic-Periodontal Lesions

(acute infections with pus accumulation). - Mucogingival Deformities and Conditions

(e.g., gingival recession, lack of keratinized tissue). - Traumatic Occlusal Forces

(e.g., clenching or bruxism causing attachment loss). - Tooth and Prosthesis-Related Factors

(e.g., overhanging restorations, root grooves).

IV. Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions

This section was entirely new in 2017, reflecting the growing prevalence of dental implants and the need to classify their associated diseases.

- Peri-Implant Health: No signs of inflammation or bone loss beyond initial remodeling.

- Peri-Implant Mucositis: Reversible inflammation of the mucosa surrounding implants, analogous to gingivitis.

- Peri-Implantitis: Inflammatory process leading to progressive bone loss around an implant.

- Peri-Implant Soft and Hard Tissue Deficiencies: Anatomical or iatrogenic defects that can compromise aesthetics or hygiene.

Major Differences Between the 1999 and 2017 Classifications

| Aspect | 1999 Classification | 2017 Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Main Focus | Types of disease | Health–disease continuum and risk assessment |

| Periodontitis Categories | Chronic and aggressive (separate entities) | Unified as one disease with staging and grading |

| Assessment Method | Based on clinical attachment loss | Based on severity, complexity, and risk factors |

| Peri-Implant Diseases | Not included | Fully integrated and classified |

| Systemic Links | Limited mention | Emphasized throughout |

| Progression | Not measured | Evaluated through grading |

| Health Definition | Implicit | Explicitly defined for both intact and reduced periodontium |

The 2017 system thus moves from a descriptive to a diagnostic and predictive model, aligning with modern precision medicine.

Clinical Importance of the 2017 Classification

The revised classification has had a major impact on clinical practice and education.

It allows dentists and hygienists to:

- Diagnose more precisely:

Staging and grading facilitate accurate recording of disease severity and progression. - Communicate more effectively:

Shared terminology enables clear interdisciplinary communication and research comparison. - Plan individualized treatment:

Risk factors like smoking or diabetes guide preventive and therapeutic strategies. - Monitor disease over time:

Clinicians can assess stability or recurrence during maintenance phases. - Include implant assessments:

Recognition of peri-implant diseases helps prevent implant failure.

Educational Implications

For dental and hygiene students, understanding both the 1999 and 2017 classifications is essential.

The 1999 framework still provides historical context and diagnostic principles, while the 2017 system represents current clinical standards.

Students should be able to:

- Identify key features of gingivitis and periodontitis.

- Recognize systemic influences on periodontal health.

- Differentiate between plaque-induced and non-plaque-induced conditions.

- Apply staging and grading to real patient cases.

- Evaluate peri-implant tissue health accurately.

Summary

The 1999 classification of periodontal diseases provided a solid foundation for diagnosing and studying gum diseases, but scientific progress and clinical experience revealed the need for a more flexible and biologically relevant framework.

The 2017 classification, developed collaboratively by the AAP and EFP, offers a comprehensive, dynamic approach that reflects modern understanding of disease mechanisms, systemic connections, and patient variability.

The key features of the 2017 system include:

- Clear definitions of health and disease.

- Unified category of periodontitis with staging and grading.

- Detailed inclusion of peri-implant diseases.

- Recognition of systemic and anatomical factors influencing periodontal health.

Ultimately, this classification empowers dental professionals to provide personalized, evidence-based care — improving not just oral health, but overall well-being.

Conclusion

Periodontal diseases are complex, multifactorial conditions that demand accurate diagnosis and effective management. Classification systems like those of 1999 and 2017 are more than academic exercises; they are practical tools guiding everyday clinical decisions.

The 2017 World Workshop classification represents a paradigm shift — moving from rigid definitions toward a holistic, patient-centered approach.

By understanding and applying this system, clinicians and students alike can better appreciate the intricate balance between health, disease, and the factors that influence both.

References

- Caton, J. G., Armitage, G., Berglundh, T., Chapple, I. L. C., Jepsen, S., Kornman, K. S., Mealey, B. L., Papapanou, P. N., Sanz, M., & Tonetti, M. S. (2018). A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions – Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. Journal of Periodontology, 89(Suppl 1), S1–S8.

- Tonetti, M. S., Greenwell, H., & Kornman, K. S. (2018). Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. Journal of Periodontology, 89(Suppl 1), S159–S172.

- Papapanou, P. N., Sanz, M., Buduneli, N., Dietrich, T., Feres, M., Fine, D. H., Flemmig, T. F., Garcia, R., Giannobile, W. V., Graziani, F., Greenwell, H., Herrera, D., Kao, R. T., Kebschull, M., Kinane, D. F., Kirkwood, K. L., Kocher, T., Kornman, K. S., Kumar, P. S., … Tonetti, M. S. (2018). Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of Periodontology, 89(Suppl 1), S173–S182.

- Chapple, I. L. C., Mealey, B. L., Van Dyke, T. E., Bartold, P. M., Dommisch, H., Eickholz, P., Geisinger, M. L., Genco, R. J., Glogauer, M., Goldstein, M., Griffin, T. J., Holmstrup, P., Johnson, G. K., Kapila, Y., Lang, N. P., Meyle, J., Murakami, S., Plemons, J., Romito, G. A., … Yoshie, H. (2018). Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop. Journal of Periodontology, 89(Suppl 1), S74–S84.

- Berglundh, T., Armitage, G., Araujo, M. G., Avila-Ortiz, G., Blanco, J., Camargo, P. M., Chen, S., Cochran, D., Derks, J., Figuero, E., Hämmerle, C., Heitz-Mayfield, L. J. A., Huynh-Ba, G., Iacono, V., Koo, K. T., Lambert, F., McCauley, L., Quirynen, M., Renvert, S., … Zitzmann, N. (2018). Peri-implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop. Journal of Periodontology, 89(Suppl 1), S313–S318.

- Armitage, G. C. (1999). Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Annals of Periodontology, 4(1), 1–6.

- Armitage, G. C. (2004). The complete periodontal examination. Periodontology 2000, 34, 22–33.

- Lindhe, J., Lang, N. P., & Karring, T. (2008). Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry (5th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard.

- Newman, M. G., Takei, H. H., Klokkevold, P. R., & Carranza, F. A. (2019). Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology (13th ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier.

- Tonetti, M. S., & Jepsen, S. (2013). Clinical concepts for regenerative therapy in intrabony defects. Periodontology 2000, 62(1), 214–240.