Periodontal diseases, including gingivitis and periodontitis, are among the most common chronic inflammatory conditions affecting humans. Their etiology is multifactorial; however, the accumulation of bacterial plaque remains the primary causative factor. The cornerstone of periodontal therapy is, therefore, the control and removal of dental plaque — a task that relies heavily on both professional and patient participation.

Non-surgical periodontal therapy (NSPT) encompasses procedures aimed at controlling infection and halting disease progression without the need for surgical intervention. Among these, plaque control—both mechanical and chemical—is paramount. The success of any periodontal treatment plan depends largely on the patient’s ability to maintain optimal oral hygiene over time.

Table of Contents

ToggleUnderstanding Dental Plaque

Definition and Composition

Dental plaque is a soft, sticky biofilm composed of bacteria, bacterial by-products, extracellular polysaccharides, and salivary components. It adheres tenaciously to tooth surfaces, restorations, and the gingival margin. The microbial ecosystem within plaque is complex, containing aerobic and anaerobic bacteria arranged in structured communities protected by a self-produced matrix.

Plaque Formation

Plaque formation occurs in distinct stages:

- Pellicle formation — Within minutes after tooth cleaning, salivary glycoproteins form an acellular film known as the acquired pellicle.

- Initial bacterial colonization — Pioneer species such as Streptococcus sanguinis and Actinomyces viscosus attach to the pellicle.

- Secondary colonization and maturation — Other bacteria adhere to primary colonizers, leading to increased microbial diversity and a shift toward a pathogenic flora dominated by Gram-negative anaerobes.

- Biofilm maturation — The biofilm becomes highly structured, developing microenvironments with differential oxygen tension and pH levels that support complex microbial interactions.

Role in Disease

Plaque biofilm is the principal etiologic agent of both gingivitis and periodontitis. While gingivitis is reversible inflammation confined to the gingiva, periodontitis involves destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. The transition from gingivitis to periodontitis is facilitated by host immune responses to persistent microbial challenge.

Principles of Non-Surgical Periodontal Therapy

The objectives of NSPT are:

- To reduce or eliminate microbial plaque and calculus.

- To create an environment conducive to periodontal healing.

- To educate and motivate the patient for lifelong plaque control.

Non-surgical therapy typically includes:

- Oral hygiene instruction (OHI)

- Mechanical debridement (scaling and root planing)

- Adjunctive chemical plaque control

- Behavioral modification and maintenance

Patient education is at the heart of plaque control. Even the most skillful professional cleaning is temporary if the patient does not maintain daily self-performed plaque control.

Oral Hygiene Instruction (OHI)

The Role of Communication

Effective OHI begins with patient understanding. Dental professionals must explain the nature of periodontal disease, its causes, and its consequences in simple terms. Visualization tools—such as diagrams, videos, or intraoral photographs—can enhance comprehension and motivation.

Motivation and Behavior Change

Motivation is a key determinant of compliance. Behavior change models, such as the Health Belief Model and Stages of Change Theory, emphasize the need to align advice with the patient’s readiness to act. Short, clear, and positive instructions combined with regular reinforcement sessions yield better outcomes than a single, information-heavy session.

Tailoring OHI

OHI must be personalized based on:

- Patient’s age and dexterity

- Type and severity of disease

- Prosthetic or orthodontic appliances

- Manual skills and psychological attitude

It is often counterproductive to overwhelm patients with complex instructions during the initial visit. Motivation should be progressive, reinforced at subsequent appointments.

Mechanical Plaque Control

Mechanical plaque removal remains the gold standard for daily oral hygiene. It involves disrupting and removing the bacterial biofilm using physical means—primarily toothbrushes and interdental cleaning aids.

Toothbrushing

Toothbrush Design

The ideal toothbrush has:

- A small head for accessibility to posterior teeth

- Soft to medium bristles with rounded ends

- A comfortable handle for effective grip

Toothbrushes should be replaced every 3–4 months or sooner if bristles splay.

Brushing Techniques

Numerous brushing techniques have been advocated, including:

- Modified Bass Technique: Bristles placed at a 45° angle to the gingival margin with gentle vibratory strokes, cleaning both tooth and sulcus.

- Stillman’s Method: Similar to Bass, with added rolling motion to massage gingiva.

- Charters Method: Bristles angled coronally for patients with gingival recession or orthodontic appliances.

- Circular (Fones) Method: Often recommended for children and individuals with limited dexterity.

The best technique is the one that the patient can perform effectively and comfortably, achieving plaque removal without causing trauma.

Powered Toothbrushes

Electric or oscillating-rotating toothbrushes have shown superior efficacy compared to manual brushes, especially in reducing plaque and gingivitis. They are particularly advantageous for patients with poor manual dexterity, orthodontic devices, or limited motivation. Modern sonic and ultrasonic brushes provide additional benefits through vibrational disruption of the biofilm.

Interdental Cleaning

Brushing alone cannot effectively clean interdental areas, where periodontal disease often initiates. Thus, interdental aids are indispensable.

Dental Floss

Flossing is effective in removing interdental plaque when performed correctly. However, improper technique may traumatize the gingiva. Studies have shown variable compliance rates, suggesting that flossing should be recommended primarily to motivated patients with tight contacts and sufficient dexterity.

Interdental Brushes

Interdental brushes (IDBs) are superior to floss for cleaning open interdental spaces and posterior teeth. The brush size must correspond to the interdental gap—too small and it will be ineffective; too large and it may cause trauma. The European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) recommends daily interdental cleaning with appropriately sized IDBs as part of standard oral hygiene practice.

Other Aids

Rubber tip stimulators, wooden sticks, and water flossers can also be used, especially in patients with periodontal pockets, implants, or fixed prostheses. Water flossers, using pulsating water jets, help remove debris and reduce bleeding but do not replace mechanical cleaning.

Chemical Plaque Control

When mechanical methods are insufficient—due to poor dexterity, limited access, or compliance—chemical agents provide an adjunctive means of controlling plaque.

Chlorhexidine (CHX)

Chlorhexidine remains the “gold standard” among antiplaque agents due to its broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and substantivity (ability to bind to oral surfaces and release slowly).

- Concentrations: 0.12–0.2% mouthrinses are most common.

- Indications: Post-surgical healing, acute gingivitis, or short-term adjunctive therapy.

- Side effects: Tooth staining, taste alteration, mucosal irritation, and increased calculus formation.

To mitigate these effects, alcohol-free formulations and anti-discoloration systems (ADS) have been developed.

Other Antiseptic Mouthrinses

- Essential oils (e.g., Listerine®): Exhibit moderate antiplaque effects; may cause a burning sensation.

- Cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC): Quaternary ammonium compound with limited substantivity but good short-term efficacy.

- Triclosan: Once popular, now largely discontinued due to regulatory concerns.

- Delmopinol: Reduces plaque adherence and gingivitis, suitable for maintenance phases.

Antiplaque Toothpastes

Toothpastes with fluoride, zinc citrate, or stannous fluoride provide mild antibacterial effects and help prevent calculus formation. Formulations with chlorhexidine or triclosan-copolymer systems have shown additional benefits in reducing gingival inflammation.

Limitations of Chemical Control

While useful as an adjunct, chemical agents cannot substitute for mechanical cleaning. Their effects are transient and often limited to supragingival areas. Overreliance without adequate brushing can give patients a false sense of security.

Professional Support in Plaque Control

Professional intervention complements patient-performed plaque control through:

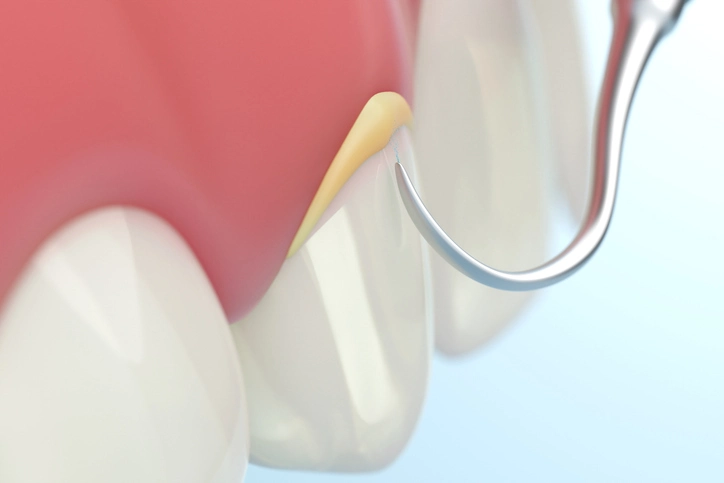

Scaling and Root Planing (SRP)

Mechanical debridement removes plaque, calculus, and bacterial toxins from tooth surfaces and root areas. SRP creates a biologically compatible surface for gingival reattachment and healing. It also enhances the effectiveness of patient home care.

Use of Disclosing Agents

Plaque disclosing tablets or solutions visualize plaque deposits, helping both clinician and patient assess cleaning effectiveness. They serve as motivational tools and educational feedback during OHI sessions.

Monitoring and Reinforcement

Regular recall visits are vital to monitor plaque levels, reinforce motivation, and adjust techniques as necessary. The clinician-patient partnership is continuous; success depends on periodic professional support.

Special Considerations in Plaque Control

Orthodontic Patients

Fixed appliances create new plaque-retentive areas around brackets and bands. Specialized brushes, interdental aids, and fluoride rinses are essential. Chlorhexidine or fluoride varnishes may be prescribed periodically.

Elderly Patients

Elderly individuals often face challenges such as arthritis, cognitive decline, or reduced salivary flow. Modified handles, electric brushes, and caregiver-assisted brushing can improve outcomes. Emphasis on gentle technique is crucial to prevent tissue trauma.

Patients with Systemic Conditions

Diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised states, or cardiovascular diseases can exacerbate periodontal inflammation. Rigorous plaque control has systemic health implications, emphasizing the bidirectional relationship between oral and systemic health.

Implant Maintenance

Dental implants are susceptible to peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis. Soft-bristled brushes, non-metallic interdental aids, and antimicrobial rinses are recommended to avoid surface damage while ensuring cleanliness.

Recent Advances in Plaque Control

Modern dentistry has witnessed innovations aimed at improving plaque removal and patient compliance.

Smart Toothbrushes

Bluetooth-enabled electric toothbrushes provide real-time feedback on brushing duration, pressure, and coverage. Such technologies enhance motivation through gamification and data tracking.

Probiotics and Oral Microbiome Therapy

Probiotics like Lactobacillus reuteri have been investigated for their ability to modulate the oral microbiota, reducing pathogenic species and inflammation. Though still emerging, microbiome-based therapies represent a promising frontier.

Nanotechnology in Oral Care

Nanoparticles with antimicrobial and remineralizing properties—such as silver, zinc oxide, and hydroxyapatite—are being integrated into toothpastes and mouthrinses, offering prolonged protection.

Salivary Diagnostics and Personalized Care

Advances in salivary biomarker testing allow early detection of inflammation, enabling customized hygiene regimens. Personalized preventive dentistry aligns with the broader shift toward precision medicine.

Conclusion

Plaque control remains the foundation of non-surgical periodontal therapy. Despite the advent of advanced technologies and chemical adjuncts, daily mechanical cleaning by the patient is irreplaceable. Effective plaque control requires education, motivation, and continuous reinforcement by dental professionals.

The clinician’s role is not only to perform debridement but to act as a mentor—guiding patients toward lifelong oral health behaviors. When properly executed, non-surgical treatment not only halts periodontal disease but enhances the overall quality of life.

Future directions in plaque control will likely integrate personalized care, digital monitoring, and microbiome modulation, but the core principle will remain unchanged: control of dental plaque through consistent, effective, and motivated oral hygiene practice.

References

- Lang NP, Bartold PM. Periodontal health. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 20):S9–S16.

- Van der Weijden F, Slot DE. Oral hygiene in the prevention of periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 2011;55(1):104–123.

- P.D. Mann. Contemporary perspective on plaque control. Br Dent J. 2012;212:601.

- Chapple ILC, et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis—consensus report of the EFP Workshop. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(S16):S5–S11.

- Addy M, Wade WG. Chemical plaque control and prevention of gingivitis. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:52–69.

- Jepsen S, et al. Mechanical and chemical plaque control in the prevention of periodontal diseases. EFP S3-level Clinical Practice Guideline. 2020.