Periodontal disease is one of the most prevalent oral health problems worldwide, characterized by inflammation of the gingiva and progressive destruction of the supporting structures of the teeth. Its impact extends beyond oral health, influencing systemic conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Understanding the epidemiology of periodontal disease and the use of standardized assessment tools, such as the Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE), is fundamental for effective diagnosis, prevention, and management.

Table of Contents

ToggleEpidemiology of Periodontal Disease

Definition and Scope

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution, determinants, and deterrents of health-related conditions in populations. In the context of periodontal disease, it involves examining the prevalence, severity, and progression of gingivitis and periodontitis among various populations, as well as identifying risk factors that contribute to disease onset and progression.

Epidemiological studies help clinicians and public health professionals understand the burden of periodontal disease, develop preventive programs, allocate resources effectively, and formulate strategies for treatment at both individual and community levels.

Periodontal Disease: An Overview

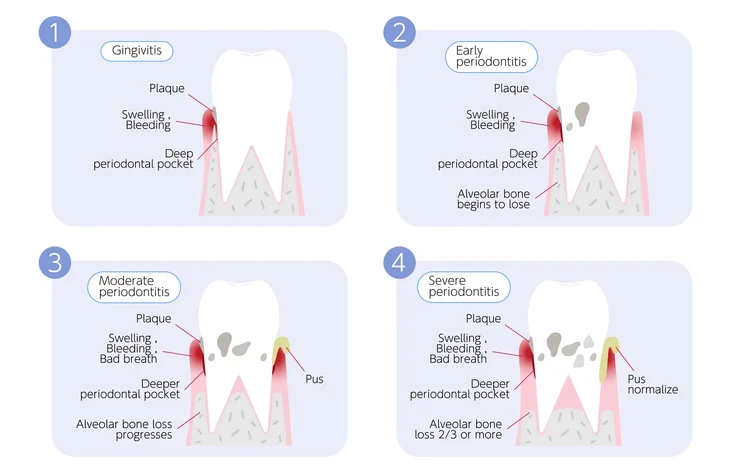

Periodontal disease encompasses two major conditions:

- Gingivitis: A reversible inflammation of the gingiva without attachment loss.

- Periodontitis: A chronic, destructive form of periodontal disease involving loss of connective tissue attachment and alveolar bone.

While gingivitis affects a large proportion of the global population, periodontitis affects fewer individuals but contributes disproportionately to tooth loss and oral disability.

Measuring Periodontal Disease

Several indices have been developed to measure periodontal conditions in population studies. These indices are used to standardize data collection, making it possible to compare findings across different populations and time periods. Some of the most widely recognized indices include:

- Gingival Index (GI) and Plaque Index (PI): Measure gingival inflammation and plaque accumulation, respectively.

- Periodontal Index (PI by Russell): An early index assessing both gingivitis and periodontitis.

- Community Periodontal Index (CPI): Developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for population-level studies.

- Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN): A refinement of the CPI that identifies not only the presence of disease but also the level of treatment required.

- Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE): A clinical adaptation of CPITN used in individual patient assessment, particularly in general dental practice.

Each of these tools has strengths and limitations. For instance, indices that include gingival bleeding may overestimate disease severity, whereas others may underestimate the early stages of attachment loss.

Prevalence and Severity

Periodontitis is one of the most widespread chronic diseases globally. Mild to moderate forms are highly prevalent, while severe periodontitis affects approximately 10–15% of adults worldwide. Epidemiological surveys indicate that:

- Gingivitis is nearly universal.

- Severe chronic periodontitis affects 5–15% of adults, depending on the population studied.

- Aggressive periodontitis (rapid attachment loss in otherwise healthy individuals) affects a small but significant minority — up to 2% in Afro-Caribbean populations and about 0.2–0.4% in Caucasians under the age of 35.

The variation in prevalence across populations can be attributed to genetic, behavioral, environmental, and socioeconomic factors.

Risk Factors and Determinants

Understanding the risk factors for periodontal disease is crucial for its prevention and control. These factors can be broadly categorized as follows:

1. Behavioral Factors:

- Plaque control: Poor oral hygiene is the most significant modifiable risk factor.

- Smoking: Smokers are up to six times more likely to develop periodontitis than non-smokers.

- Diet: Deficiencies in vitamin C and other micronutrients can impair healing and immune response.

2. Systemic Factors:

- Diabetes mellitus: Poorly controlled diabetes is a major risk factor, leading to impaired host response and delayed healing.

- Hormonal changes: Puberty, pregnancy, and menopause can increase susceptibility due to hormonal fluctuations.

- Systemic diseases: Conditions such as HIV, osteoporosis, and rheumatoid arthritis influence periodontal health.

3. Genetic Factors:

Certain genetic polymorphisms influence immune and inflammatory responses, increasing susceptibility to aggressive forms of periodontitis.

Socioeconomic and Environmental Factors:

Access to dental care, education, income level, and health awareness all play roles in disease prevalence and management.

Emerging Trends in Epidemiological Research

Despite significant progress, gaps remain in understanding the natural history and progression of periodontal disease. Longitudinal studies are essential to identify causal relationships and to evaluate the effectiveness of preventive and therapeutic strategies. The integration of genomics, microbiomics, and artificial intelligence into periodontal epidemiology offers promising avenues for personalized dental care in the future.

Clinical Assessment: The Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE)

Development and Purpose

The Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) evolved from the Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN). Developed by the British Society of Periodontology, the BPE provides a rapid, standardized screening method to assess the periodontal status of patients and determine whether further detailed examination or treatment is required.

Unlike comprehensive periodontal charting, the BPE is a screening tool, not a diagnostic measure. It helps clinicians quickly identify areas that require further investigation, treatment, or referral to a specialist.

Equipment and Method

The WHO periodontal probe is used for BPE recording. The probe has a 0.5 mm ball tip to minimize tissue trauma and a black band between 3.5 mm and 5.5 mm to visually measure pocket depth.

Mouth division:

The mouth is divided into six sextants:

- UR (upper right) 4–7

- UL (upper left) 4–7

- LR (lower right) 4–7

- LL (lower left) 4–7

- UR anterior (UR1–3)

- UL anterior (UL1–3)

Each sextant must contain at least two teeth to qualify for scoring. If a sextant contains only one tooth, it is combined with an adjacent sextant.

Probing Technique

- A light probing force (20–25 grams) should be used.

- The probe is gently “walked” around the gingival sulcus to detect the deepest pocket.

- The highest score for each sextant is recorded.

Interpretation of BPE Codes

The BPE uses a numeric coding system (0–4) to describe the condition of the periodontium, with an additional symbol (*) for furcation involvement.

Code 0

- Pocket depth <3.5 mm (black band completely visible).

- No bleeding after gentle probing.

- No calculus or defective margins.

Interpretation: Healthy periodontium.

Action: No treatment required other than routine preventive care and reinforcement of oral hygiene instruction (OHI).

Code 1

- Pocket depth <3.5 mm (black band completely visible).

- Bleeding observed after gentle probing.

- No plaque-retentive factors.

Interpretation: Gingivitis present.

Action: Provide oral hygiene instruction (OHI). Reinforce brushing technique and interdental cleaning.

Code 2

- Pocket depth <3.5 mm (black band visible).

- Plaque-retentive factors present (e.g., calculus, overhanging restoration margins).

Interpretation: Early signs of plaque accumulation and local contributing factors.

Action:

- OHI plus scaling and removal of subgingival and supragingival deposits.

- Record plaque and bleeding scores.

- Monitor oral hygiene performance.

Code 3

Pocket depth of 4–5 mm (black band partially visible in the deepest site of the sextant).

Interpretation: Shallow periodontal pockets indicating mild to moderate periodontitis.

Action:

- Detailed periodontal charting for affected sextants (six-point probing per tooth).

- Scaling and root surface debridement.

- Radiographs to evaluate bone levels.

- Review after 3 months; if pocketing persists, re-instrumentation may be needed.

Code 4

Pocket depth >5.5 mm (black band disappears completely).

Interpretation: Deep periodontal pockets with probable attachment loss.

Action:

- Full-mouth periodontal charting.

- Radiographic assessment of bone loss.

- Comprehensive periodontal therapy including root surface debridement.

- Referral to a specialist periodontist if necessary.

Code *

Furcation involvement (horizontal bone loss exposing the area between roots).

Interpretation: Advanced periodontal breakdown.

Action:

- Full periodontal charting, furcation assessment, and radiographs.

- Specialist referral may be indicated for complex management.

Clinical Considerations and Limitations

While the BPE is an invaluable tool in general dental practice, clinicians should be aware of its limitations:

- Screening Only:

The BPE does not provide information about the specific site of disease or longitudinal changes. It cannot monitor treatment outcomes effectively. - Not Suitable for Implants:

BPE probing is inappropriate for implant sites because peri-implant soft tissue differs anatomically from natural gingiva. Implant tissues are less resistant to probing, and deeper readings may not necessarily indicate disease. - Requires Clinical Judgment:

A high BPE code does not always correlate with disease severity; clinical judgment, radiographs, and comprehensive assessment are essential for accurate diagnosis. - Consistency in Technique:

Variability in probing force or angulation can affect results, emphasizing the need for clinician calibration and consistency.

Clinical Application and Management

Recording and Documentation

Each sextant’s BPE score should be clearly documented in the patient’s chart. The highest score per sextant determines the clinical action required. This facilitates:

- Quick reference for future assessments.

- Communication with other dental professionals.

- Legal documentation of baseline periodontal status.

Using the BPE for Risk Assessment

The BPE can guide clinicians in identifying patients at high risk for progressive disease. For example:

- A patient with generalized code 3 or 4 readings may need more frequent maintenance visits.

- A patient with consistent code 0–1 readings can be maintained on a standard recall interval.

Additional risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, or genetic predisposition should be considered when tailoring preventive care plans.

Role in Preventive Dentistry

The ultimate goal of the BPE is not just to detect disease but to promote early intervention and prevention. Regular screening encourages patients to maintain good oral hygiene and allows clinicians to reinforce preventive advice before irreversible damage occurs.

Periodontal Disease as a Public Health Concern

Periodontal disease represents a significant public health issue because of its high prevalence, chronicity, and association with systemic diseases. Its impact extends beyond tooth loss; it affects mastication, aesthetics, self-esteem, and overall quality of life.

The World Health Organization emphasizes integrating periodontal care into general health programs. Public health initiatives should focus on:

- Education and awareness about plaque control.

- Smoking cessation programs.

- Regular dental check-ups and community-based screenings.

- Access to affordable periodontal care, especially in underserved populations.

Epidemiological data from BPE and CPI surveys play a critical role in shaping these policies.

Advances in Periodontal Assessment

While the BPE remains a practical screening tool, modern technology is enhancing periodontal assessment through:

- Digital probing systems: Providing automated depth readings and digital records.

- 3D imaging and CBCT scans: Allowing detailed visualization of bone architecture.

- Biomarker analysis: Identifying host responses and bacterial profiles to predict disease risk.

- Artificial intelligence (AI): Assisting in interpreting large epidemiological datasets to identify patterns and predict outcomes.

These innovations are not intended to replace traditional methods like the BPE but rather to complement them for more personalized and accurate care.

Conclusion

The understanding and management of periodontal disease rely on a combination of epidemiological insight and clinical precision. The Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) offers a simple, reliable, and cost-effective means of identifying periodontal problems early. However, it must be interpreted within a comprehensive diagnostic framework that includes radiographic assessment, risk factor evaluation, and individualized treatment planning.

As research continues to unravel the intricate links between periodontal health and systemic well-being, clinicians must integrate epidemiological knowledge with clinical acumen. Regular BPE screening, patient education, and preventive care remain the cornerstone of periodontal health — ensuring that the silent burden of periodontal disease is addressed effectively across populations.

References

- Albandar, J. M., & Rams, T. E. (2002). Global epidemiology of periodontal diseases: An overview. Periodontology 2000, 29(1), 7–10.

- Armitage, G. C. (1999). Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Annals of Periodontology, 4(1), 1–6.

- Armitage, G. C. (2004). Periodontal diagnoses and classification of periodontal diseases. Periodontology 2000, 34(1), 9–21.

- Bourgeois, D., Inquimbert, C., Ottolenghi, L., & Carrouel, F. (2017). Periodontal diseases: Major public health problems. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 6(12), 12.

- British Society of Periodontology. (2016). The Good Practitioner’s Guide to Periodontology (2nd ed.). BSP.

- Chapple, I. L. C., Mealey, B. L., Van Dyke, T. E., Bartold, P. M., Dommisch, H., Eickholz, P., … & Jepsen, S. (2018). Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 45(S20), S68–S77.

- Eke, P. I., Dye, B. A., Wei, L., Slade, G. D., Thornton-Evans, G. O., Borgnakke, W. S., … & Genco, R. J. (2015). Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009–2012. Journal of Periodontology, 86(5), 611–622.

- Genco, R. J., & Borgnakke, W. S. (2020). Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontology 2000, 62(1), 59–94.

- Löe, H., & Silness, J. (1963). Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 21(6), 533–551.

- Papapanou, P. N., Sanz, M., Buduneli, N., Dietrich, T., Feres, M., Fine, D. H., … & Tonetti, M. S. (2018). Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. Journal of Periodontology, 89(S1), S173–S182.

- Petersen, P. E., Ogawa, H., & Bourgeois, D. (2020). The global burden of periodontal disease and the future of periodontal health. Periodontology 2000, 84(1), 7–25.

- Tugnait, A., & Clerehugh, V. (2001). Periodontal probing: The effect of probe type and probing force on probing measurements. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 28(5), 438–445.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2013). Oral health surveys: Basic methods (5th ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Tonetti, M. S., & Jepsen, S. (2013). Clinical guidelines for the management of periodontal diseases in general dental practice. European Federation of Periodontology (EFP).

- Van Dyke, T. E., & Bartold, P. M. (2013). An historical perspective on the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of periodontal disease. Journal of Periodontology, 84(4S), S4–S12.