Pemphigus is a group of rare autoimmune disorders that cause blistering of the skin and mucous membranes, including the oral cavity. It is characterized by the body’s immune system mistakenly attacking healthy cells in the skin and mucosa, leading to painful blisters and sores. Pemphigus can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life, especially when oral lesions are present, as they can interfere with basic functions like eating, speaking, and swallowing. This article delves deep into the nature of pemphigus, its types, the oral symptoms associated with it, and the available treatment options.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is Pemphigus?

Pemphigus is primarily classified as an autoimmune disease where the body’s immune system targets proteins in the skin called desmogleins, which are crucial for maintaining the adhesion of skin cells. When these proteins are attacked, it results in a separation of skin cells (a process known as acantholysis), which leads to the formation of blisters.

The condition is categorized into several types, including:

- Pemphigus vulgaris (PV)

- Pemphigus foliaceus (PF)

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP)

- IgA pemphigus

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV)

The most common and severe form of pemphigus, predominantly affecting the skin and mucous membranes, particularly in the mouth.

Pemphigus foliaceus (PF)

A milder form that usually affects only the skin and does not involve mucous membranes.

Paraneoplastic pemphigus (PNP)

A rare and often severe variant associated with underlying malignancies.

IgA pemphigus

Another rare form characterized by the deposition of IgA antibodies.

Of these, pemphigus vulgaris is the most relevant when discussing oral symptoms, as it typically manifests first in the mouth and can lead to significant discomfort and complications.

Epidemiology of Pemphigus

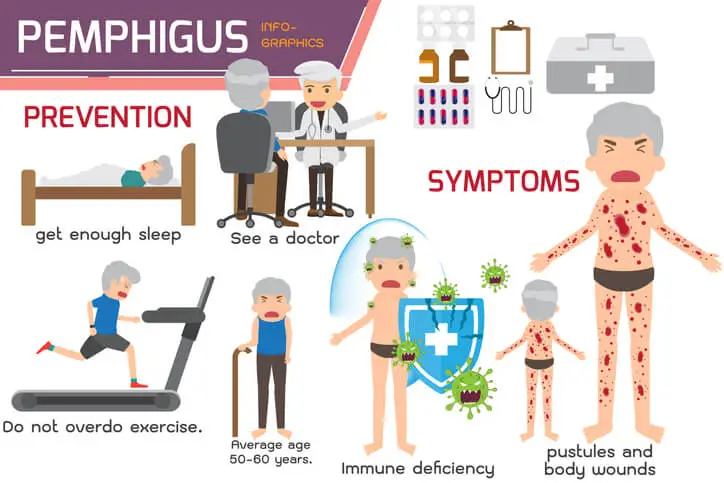

Pemphigus is a relatively rare disorder, with an incidence ranging between 0.1 to 0.5 cases per 100,000 individuals per year globally. It tends to be more prevalent in certain populations, such as Ashkenazi Jews, Southeast Europeans, and individuals from the Mediterranean region. The disease usually manifests in middle-aged and older adults, though cases in younger individuals have been documented. Both men and women are equally affected by pemphigus vulgaris.

Pathophysiology of Pemphigus

To understand the oral manifestations of pemphigus, it is essential to comprehend the underlying pathophysiology. Pemphigus is caused by the production of autoantibodies that attack specific proteins responsible for cell-to-cell adhesion in the epidermis and mucosal layers. In pemphigus vulgaris, the primary target of these autoantibodies is desmoglein 3, a protein that plays a critical role in binding keratinocytes together in the skin and mucosal tissues.

When the immune system mistakenly produces antibodies against desmoglein 3, it disrupts the normal adhesion of cells, resulting in acantholysis. This causes the outer layers of the skin and mucous membranes to separate, leading to the formation of blisters. These blisters are often fragile, easily ruptured, and can leave behind painful, non-healing erosions.

Oral Symptoms of Pemphigus

Oral lesions are often the first and sometimes the only sign of pemphigus vulgaris, preceding skin involvement by months or even years. In some patients, pemphigus may remain confined to the oral cavity without progressing to other parts of the body. These oral symptoms can be debilitating, making diagnosis and treatment crucial to prevent further complications.

- Blisters and Erosions

- Pain and Discomfort

- Gingival Involvement (Desquamative Gingivitis)

- Nikolsky’s Sign

- Difficulty in Swallowing (Dysphagia)

- Involvement of Other Mucosal Surfaces

Blisters and Erosions

The hallmark of oral pemphigus is the development of fragile blisters in the mouth. These blisters are filled with clear fluid and can appear on any mucosal surface, including the:

- Inner cheeks (buccal mucosa)

- Gums (gingiva)

- Palate

- Lips

- Tongue

- Floor of the mouth

Due to the delicate nature of the oral mucosa, these blisters often rupture quickly, leaving behind raw, painful erosions. These erosions are typically slow to heal and can persist for weeks or months, leading to chronic discomfort. The lesions are often irregularly shaped and vary in size from small erosions to larger ulcerative areas.

Pain and Discomfort

One of the most significant symptoms of oral pemphigus is pain. The erosions and ulcers left behind after blister rupture are extremely sensitive, making simple actions like talking, eating, and drinking painful. Hot or spicy foods, in particular, can exacerbate the pain, causing patients to avoid eating certain foods, which may lead to nutritional deficiencies and weight loss.

Gingival Involvement (Desquamative Gingivitis)

Desquamative gingivitis is a characteristic finding in patients with pemphigus vulgaris and other autoimmune blistering diseases. It refers to the sloughing or peeling of the gingival epithelium, resulting in red, raw, and painful gums. The gingiva may bleed easily during brushing or eating and often appears inflamed.

This condition can be mistaken for more common gingival disorders, such as periodontal disease, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of pemphigus. Patients may complain of gum tenderness, bleeding, and difficulty maintaining oral hygiene due to pain.

Nikolsky’s Sign

A key diagnostic feature of pemphigus is Nikolsky’s sign, which refers to the ability to induce blistering or peeling of the mucosa by applying slight pressure or friction. In the oral cavity, Nikolsky’s sign can be elicited by rubbing the gingiva or buccal mucosa with a cotton swab or finger. A positive Nikolsky’s sign suggests a loss of adhesion between epithelial cells, which is indicative of pemphigus.

Difficulty in Swallowing (Dysphagia)

Severe oral lesions, especially those affecting the soft palate, tongue, or floor of the mouth, can lead to difficulty swallowing, a condition known as dysphagia. This can further compound the challenges of eating and drinking, leading to weight loss, dehydration, and malnutrition if left untreated.

Involvement of Other Mucosal Surfaces

In addition to the mouth, pemphigus can affect other mucosal surfaces, including the throat (pharyngeal mucosa), nose, eyes, and genitals. In the oral cavity, the involvement of the throat may lead to hoarseness, sore throat, or difficulty swallowing. Nasal lesions may cause nosebleeds or crusting, while ocular lesions can result in conjunctivitis or dry eyes.

Diagnosis of Oral Pemphigus

Given the rarity and non-specific nature of the symptoms, diagnosing pemphigus can be challenging. Oral lesions can mimic other common conditions, such as aphthous ulcers, lichen planus, and periodontal disease. Therefore, accurate diagnosis requires a combination of clinical examination, histopathology, and immunological testing.

- Clinical Examination

- Biopsy and Histopathology

- Direct Immunofluorescence

- Indirect Immunofluorescence and ELISA

Clinical Examination

A thorough clinical examination of the oral cavity is essential for identifying the characteristic blisters, erosions, and gingival involvement associated with pemphigus. A positive Nikolsky’s sign during the examination can further raise suspicion of the disease.

Biopsy and Histopathology

A biopsy of the affected mucosa is typically performed to confirm the diagnosis. The sample is then analyzed under a microscope for the presence of acantholysis, or the loss of cell-to-cell adhesion, which is a hallmark of pemphigus. The histopathological examination may reveal the presence of intraepithelial blisters, which are formed due to the separation of keratinocytes.

Direct Immunofluorescence

Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is a critical diagnostic tool for pemphigus. A biopsy sample is stained with fluorescent antibodies to detect the presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and complement proteins (C3) that are bound to the desmogleins. In pemphigus, these antibodies are deposited in a characteristic pattern between keratinocytes, giving a “fishnet” or “honeycomb” appearance.

Indirect Immunofluorescence and ELISA

Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) can also be used to detect circulating antibodies against desmoglein 1 and desmoglein 3 in the patient’s blood. ELISA tests are particularly useful for monitoring disease activity and treatment response.

Differential Diagnosis of Oral Pemphigus

Because pemphigus can present with symptoms similar to other oral conditions, it is important to distinguish it from other disorders. Some of the key differential diagnoses include:

- Lichen planus: A chronic inflammatory condition that can cause white, lacy patches and painful sores in the mouth.

- Mucous membrane pemphigoid: Another autoimmune blistering disorder that primarily affects the mucous membranes, but typically causes subepithelial blisters rather than intraepithelial blisters.

- Aphthous stomatitis: Commonly known as canker sores, this condition causes small, painful ulcers in the mouth, but lacks the widespread erosions seen in pemphigus.

- Erythema multiforme: A hypersensitivity reaction that can cause painful sores and blisters in the mouth and other mucosal surfaces, often triggered by infections or medications.

Treatment of Oral Pemphigus

Treatment of pemphigus focuses on controlling the autoimmune response, reducing inflammation, and managing symptoms. Given that oral lesions can be particularly painful and debilitating, effective treatment is crucial to improve the patient’s quality of life.

- Systemic Corticosteroids

- Immunosuppressive Agents

- Biologic Therapy

- Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

- Topical Treatments

- Plasmapheresis

Systemic Corticosteroids

Systemic corticosteroids, such as prednisone, are the mainstay of treatment for pemphigus. Corticosteroids work by suppressing the immune system’s abnormal response, thus reducing inflammation and preventing further blister formation. However, long-term use of high-dose corticosteroids carries significant risks, including weight gain, osteoporosis, diabetes, hypertension, and increased susceptibility to infections. Therefore, while corticosteroids can be effective, they are often used in combination with other medications to minimize the dosage required and avoid adverse effects.

Immunosuppressive Agents

To reduce the reliance on corticosteroids and achieve long-term control of the disease, immunosuppressive agents are frequently prescribed. These medications work by suppressing the overactive immune response that targets desmoglein proteins. Common immunosuppressive agents used in the treatment of pemphigus include:

- Azathioprine: A purine synthesis inhibitor that interferes with DNA production in rapidly dividing cells, such as immune cells.

- Mycophenolate mofetil: Similar to azathioprine, this drug inhibits immune cell proliferation by targeting purine synthesis.

- Cyclophosphamide: An alkylating agent that suppresses the immune system by interfering with DNA replication.

- Methotrexate: Another immunosuppressant that inhibits folic acid metabolism, affecting the production of immune cells.

These medications can be effective in reducing disease activity but come with their own risks, such as bone marrow suppression, liver toxicity, and increased vulnerability to infections.

Biologic Therapy

In recent years, biologic therapies have emerged as a promising treatment option for pemphigus, particularly in cases that are refractory to traditional immunosuppressive therapies. The most well-known biologic agent used in pemphigus treatment is rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets CD20, a protein found on B cells. Since B cells are responsible for producing the autoantibodies that attack desmoglein proteins, depleting them with rituximab can lead to a significant reduction in disease activity.

Rituximab has shown considerable efficacy in achieving long-term remission in many patients with pemphigus vulgaris, and it is often used in combination with corticosteroids or as a steroid-sparing agent.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG)

IVIG therapy involves infusions of pooled immunoglobulins (antibodies) from healthy donors, which can help modulate the immune system and reduce the production of pathogenic autoantibodies. IVIG is often used as an adjunctive therapy for patients with severe or treatment-resistant pemphigus, especially when other immunosuppressive agents have failed.

Topical Treatments

While systemic therapies are crucial for controlling the underlying autoimmune process, topical treatments can provide symptomatic relief for oral pemphigus. Corticosteroid mouth rinses, gels, and ointments can help reduce inflammation and pain in localized areas. Antiseptic mouthwashes or saltwater rinses may also be recommended to reduce the risk of secondary infections in the oral lesions.

Topical anesthetics, such as lidocaine gel, can be applied to the erosions to numb the area and provide temporary pain relief, particularly before eating or performing oral hygiene.

Plasmapheresis

In severe cases, plasmapheresis, or therapeutic plasma exchange, may be used to remove circulating autoantibodies from the blood. This procedure involves filtering the patient’s blood to remove the harmful antibodies that attack desmogleins, followed by the infusion of replacement plasma. While plasmapheresis can be effective in reducing disease activity, it is usually reserved for patients with life-threatening or refractory disease.

Management of Oral Symptoms in Pemphigus

The management of oral symptoms in pemphigus requires a multifaceted approach that addresses both the underlying autoimmune disease and the local oral complications. Here are some strategies to manage and alleviate the oral symptoms associated with pemphigus:

- Oral Hygiene

- Dietary Modifications

- Pain Management

- Regular Dental Visits

- Psychological Support

Oral Hygiene

Maintaining good oral hygiene is essential for preventing secondary infections and promoting healing of the erosions. However, due to the sensitivity of the oral mucosa, patients may find brushing and flossing painful. Soft-bristled toothbrushes or foam swabs should be used to gently clean the teeth and gums without irritating the lesions. Alcohol-free mouthwashes, saline rinses, or antimicrobial agents may also be recommended to keep the mouth clean without causing further irritation.

Dietary Modifications

Patients with oral pemphigus often need to modify their diet to minimize discomfort. Avoiding hot, spicy, acidic, or rough-textured foods can help reduce irritation of the oral lesions. Soft, bland foods that are easy to chew and swallow, such as yogurt, mashed potatoes, and scrambled eggs, are typically well-tolerated. Drinking plenty of fluids and avoiding alcohol and smoking can also help promote healing and reduce irritation in the mouth.

Pain Management

Pain management is crucial for patients with oral pemphigus, as the erosions can cause significant discomfort. In addition to topical anesthetics, systemic pain relievers such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen can be used to manage pain. For severe pain, stronger prescription medications may be necessary.

Regular Dental Visits

Patients with pemphigus should see a dentist regularly for monitoring and management of oral lesions. Dental professionals can provide guidance on maintaining oral hygiene, managing pain, and preventing secondary infections. In some cases, custom-made mouthguards may be prescribed to protect the oral mucosa from further trauma.

Psychological Support

Living with a chronic autoimmune disease like pemphigus can take a toll on a patient’s mental health. The pain and discomfort associated with oral symptoms, combined with the social and functional impacts of the disease, can lead to anxiety, depression, and a decreased quality of life. Psychological support and counseling may be beneficial for patients to cope with the emotional challenges of living with pemphigus.

Prognosis of Oral Pemphigus

With appropriate treatment, many patients with pemphigus can achieve long-term remission or significant improvement in their symptoms. However, pemphigus is a chronic disease, and relapses can occur, especially when treatment is discontinued or tapered too quickly. Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of treatment are key to preventing complications and improving outcomes.

For patients with oral pemphigus, maintaining long-term follow-up with a healthcare provider is essential to monitor disease activity, adjust medications as needed, and manage side effects from treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What causes pemphigus?

Pemphigus is an autoimmune disease in which the immune system mistakenly attacks the proteins (desmogleins) that help skin cells stick together. This results in blistering and sores on the skin and mucous membranes, such as in the mouth, throat, nose, eyes, and genitals. The exact cause is not entirely understood, but a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental factors may play a role. In some cases, pemphigus can be triggered by medications such as penicillamine, captopril, or certain antibiotics. Viral infections and other autoimmune conditions may also contribute to its development.

What medication is used for pemphigus?

Treatment for pemphigus focuses on suppressing the immune system to stop the body from attacking its own skin. The primary medications used include:

- Corticosteroids (such as prednisone) – These help reduce inflammation and blister formation but can have significant side effects if used long-term.

- Immunosuppressants (such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide) – These medications help reduce the immune system’s activity and allow for lower doses of corticosteroids.

- Biologic therapy (such as rituximab) – This is a monoclonal antibody treatment that targets B-cells, which are responsible for producing the harmful antibodies in pemphigus. It is often used for moderate to severe cases and has shown promising results in achieving remission.

- Other treatments – In some cases, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) or plasmapheresis (a procedure that removes harmful antibodies from the blood) may be used for severe or treatment-resistant pemphigus.

Will pemphigus ever go away?

Pemphigus is a chronic condition, meaning it does not completely go away on its own. However, with appropriate treatment, it can be managed effectively, and many patients experience long periods of remission. Some people may eventually be able to stop treatment, while others may need ongoing low-dose medication to prevent flare-ups. Early diagnosis and treatment can help improve long-term outcomes and reduce complications.

What is the life expectancy of someone with pemphigus?

With modern treatments, most people with pemphigus have a normal life expectancy. In the past, before effective therapies were available, pemphigus was often fatal due to severe skin damage, infections, and complications. Today, with corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and biologic treatments like rituximab, the disease is much more manageable. However, life expectancy can be affected by complications such as infections, medication side effects (such as osteoporosis or diabetes from long-term steroid use), and secondary conditions related to immune suppression.

Who is most likely to get pemphigus?

Pemphigus typically affects middle-aged and older adults, with the average age of onset between 40 and 60 years. It is more common in certain ethnic groups, particularly those of Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, Ashkenazi Jewish, and South Asian descent. Genetic factors play a significant role, as people with a family history of autoimmune diseases are at higher risk. While rare, pemphigus can also develop in younger adults and, in some cases, be triggered by certain medications or infections.

What foods trigger pemphigus?

While there is no universally recognized diet for pemphigus, some patients report that certain foods can trigger or worsen their symptoms. These include:

- Foods containing thiols or isothiocyanates – Found in garlic, onions, leeks, and cruciferous vegetables (such as broccoli and cauliflower), these compounds may trigger flares in some individuals.

- Acidic foods – Citrus fruits, tomatoes, and vinegar-based products can irritate blisters, especially in the mouth.

- Spicy foods – Can aggravate oral lesions and cause discomfort.

- Processed foods – High in preservatives and artificial additives, which some believe may contribute to immune system reactions.

- Gluten – Some people with autoimmune diseases, including pemphigus, report improvement on a gluten-free diet, though research is limited.

Since food triggers vary among individuals, keeping a food diary and tracking flare-ups may help identify personal triggers.

Is pemphigus caused by stress?

Stress does not directly cause pemphigus, but it can be a significant trigger for flare-ups. Emotional and physical stress can weaken the immune system and make the body more susceptible to autoimmune activity. Many people with pemphigus report worsening symptoms during periods of high stress, illness, or trauma. Stress management techniques, such as meditation, therapy, regular exercise, and proper sleep, can help reduce the impact of stress on the condition.

What vitamin is deficient in pemphigus?

Research has shown that people with pemphigus may have deficiencies in certain vitamins, particularly:

- Vitamin D – Low vitamin D levels have been linked to various autoimmune diseases, including pemphigus. Adequate levels are important for immune regulation and skin health.

- Vitamin B12 and folic acid – Some patients with pemphigus, especially those with autoimmune comorbidities, may have deficiencies in these vitamins.

- Zinc – A mineral that plays a role in immune function and wound healing, which may be beneficial for managing pemphigus symptoms.

Although vitamin deficiencies are not the direct cause of pemphigus, maintaining a well-balanced diet and taking supplements if needed may help support overall health and disease management.

Does pemphigus make you feel ill?

Yes, pemphigus can cause systemic symptoms in addition to skin blisters. Many patients experience:

- Fatigue and weakness

- Pain and discomfort from skin lesions

- Difficulty eating if oral sores are present

- Increased risk of infections due to open wounds and immune suppression from treatment

- Emotional distress, anxiety, or depression due to the chronic nature of the disease

Managing the disease with proper medical treatment, pain relief, and emotional support can help improve quality of life.

Does pemphigus qualify for disability?

In severe cases, pemphigus can qualify for disability benefits. If the condition significantly impairs a person’s ability to work due to pain, fatigue, difficulty eating, or frequent medical treatments, they may be eligible for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) or other disability programs. Documentation from a healthcare provider, including medical records and treatment history, is typically required to support a disability claim.

Is pemphigus cancerous?

No, pemphigus is not cancer. It is an autoimmune disorder, meaning the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own healthy cells. However, because people with pemphigus often require long-term immunosuppressive treatments, they may have an increased risk of developing certain cancers, such as skin cancers and lymphomas, due to a weakened immune system.

Can you live a normal life with pemphigus?

Yes, many people with pemphigus can lead fulfilling lives with proper treatment and disease management. While pemphigus can be challenging and may require long-term medication, lifestyle adjustments, and medical follow-ups, advances in treatment have made it much more manageable. With the right care, many patients achieve remission or minimal disease activity, allowing them to participate in daily activities, work, and social life.

Conclusion

Pemphigus, particularly pemphigus vulgaris, is a rare but serious autoimmune disease that frequently manifests with oral symptoms. The painful blisters and erosions that develop in the mouth can severely impact a patient’s quality of life, making early diagnosis and treatment crucial. While systemic therapies such as corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and biologics play a central role in controlling the disease, the management of oral symptoms requires a comprehensive approach that includes pain relief, oral hygiene, and dietary modifications. With advances in treatment, many patients with pemphigus can achieve remission and lead relatively normal lives, though ongoing management is typically required.

For patients, dentists, and healthcare providers, awareness of the oral manifestations of pemphigus and an understanding of its treatment options are essential to improving outcomes and ensuring a better quality of life for those affected by this challenging condition.