Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a long term, progressive lung disease that is characterized by chronic airflow limitation. It includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis and is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. COPD affects the airways and the alveoli, resulting in obstructed airflow that interferes with normal breathing. Despite being preventable and treatable, COPD remains a major public health challenge due to underdiagnosis, especially in developing countries. In this article, we delve into the various aspects of COPD, including its causes, risk factors, symptoms, diagnostic procedures, management strategies, complications, and current research directions.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is COPD?

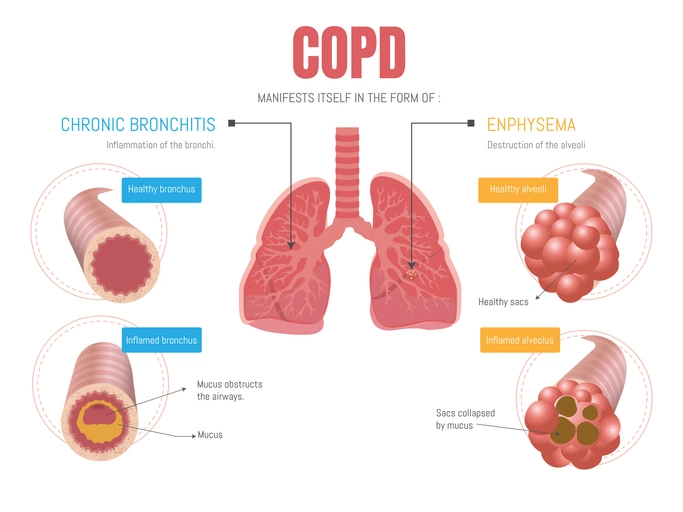

COPD is a chronic inflammatory lung disease that causes obstructed airflow from the lungs. It is mainly composed of two conditions:

- Chronic Bronchitis: This involves inflammation and narrowing of the bronchial tubes, leading to increased mucus production. It is clinically defined by a productive cough lasting for at least three months in each of two consecutive years.

- Emphysema: A condition where the alveoli, the tiny air sacs in the lungs, are damaged. This leads to a reduction in the surface area for gas exchange and results in the trapping of air in the lungs.

Both conditions are often present in people with COPD, and the degree to which each contributes to the disease varies among individuals. The disease leads to reduced airflow, which is not fully reversible, and results in difficulty breathing, frequent respiratory infections, and a decline in quality of life.

Epidemiology

COPD is one of the top causes of death globally, and its prevalence is expected to increase due to continued exposure to risk factors and the aging population. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 250 million people suffer from COPD, and it is projected to become the third leading cause of death by 2030.

The disease primarily affects individuals over the age of 40. In many countries, particularly in low and middle income regions, COPD is underdiagnosed due to limited access to healthcare and diagnostic tools. Men historically have had higher rates of COPD due to higher smoking prevalence, but as smoking among women rises, the gender gap in COPD incidence is narrowing. Occupational exposures and indoor air pollution also contribute significantly to the disease burden, particularly in regions where biomass fuels are used for cooking and heating.

Causes and Risk Factors

Primary Causes

- Tobacco Smoke: The leading cause of COPD is long-term cigarette smoking. Pipe, cigar, and other forms of tobacco smoking can also contribute. Smoking damages the airways and lung tissue, leading to inflammation, narrowed air passages, and destruction of alveoli.

- Occupational Exposures: Jobs involving exposure to dust, chemicals, and fumes increase the risk of developing COPD. Construction workers, miners, and those working in factories are particularly at risk.

- Indoor Air Pollution: In many developing countries, indoor air pollution from burning wood, coal, and other biomass fuels in poorly ventilated spaces is a major risk factor.

- Outdoor Air Pollution: Exposure to air pollutants from traffic and industrial emissions can aggravate symptoms and contribute to the development and progression of COPD.

Genetic and Other Risk Factors

- Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: This rare genetic condition affects the production of a protein that protects the lungs. Its deficiency can lead to early-onset emphysema, especially in nonsmokers.

- Respiratory Infections: Frequent childhood respiratory infections can impair lung development and increase vulnerability to COPD later in life.

- Age and Gender: COPD is more common in individuals aged 40 and above. While it used to be more prevalent in men, changing smoking patterns have led to an increase in COPD cases among women.

- Socioeconomic Status: People from lower socioeconomic backgrounds often have increased exposure to risk factors such as pollution and smoking, along with limited access to healthcare.

Pathophysiology

The hallmark of COPD is airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. This limitation is due to a combination of small airways disease (obstructive bronchiolitis) and parenchymal destruction (emphysema).

- Airway Inflammation: Chronic exposure to irritants such as cigarette smoke leads to persistent inflammation in the bronchi. This causes structural changes and narrowing of the small airways.

- Airway Remodeling: Prolonged inflammation results in fibrosis and thickening of the airway walls, reducing airway caliber.

- Alveolar Destruction: In emphysema, the destruction of alveolar walls leads to the loss of elastic recoil, impairing the lungs’ ability to expel air. This results in air trapping and hyperinflation.

- Mucociliary Dysfunction: The function of the cilia in the airways is impaired, reducing the clearance of mucus and pathogens, which can lead to recurrent infections.

Symptoms of COPD

Symptoms typically develop slowly and worsen over time. The main clinical features include:

- Chronic Cough: Often one of the earliest symptoms. It may be intermittent at first but becomes persistent over time.

- Sputum Production: The cough is usually productive, with sputum that may be clear, white, yellow, or green.

- Dyspnea (Shortness of Breath): This usually starts during exertion and progresses to dyspnea at rest as the disease advances.

- Wheezing and Chest Tightness: As the airways narrow, breathing becomes more labored, and patients may experience a feeling of chest constriction.

- Fatigue: Decreased oxygen levels and the increased effort of breathing can result in generalized fatigue.

- Weight Loss and Muscle Wasting: In advanced stages, systemic inflammation and increased energy expenditure can lead to unintentional weight loss and cachexia.

- Frequent Respiratory Infections: COPD patients are more prone to bronchitis, pneumonia, and other infections.

Exacerbations

Exacerbations are episodes of worsening symptoms, particularly dyspnea, cough, and sputum production. These are commonly triggered by infections or environmental pollutants. Frequent exacerbations are associated with faster disease progression and increased risk of hospitalization and death.

Diagnosis of COPD

Clinical Evaluation

Diagnosis begins with a thorough history and physical examination:

- Medical History: Includes smoking history, exposure to environmental and occupational pollutants, and history of respiratory symptoms.

- Physical Examination: May reveal wheezing, prolonged expiration, hyperinflation (barrel chest), and use of accessory muscles for breathing.

Pulmonary Function Testing (Spirometry)

Spirometry is essential for diagnosis:

- FEV1 (Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second): Measures how much air a person can exhale in one second.

- FVC (Forced Vital Capacity): The total amount of air exhaled during the spirometry test.

- FEV1/FVC Ratio: A ratio less than 0.70 after bronchodilator administration confirms airflow limitation.

Additional Diagnostic Tools

- Chest Imaging: Chest X-rays may show signs of hyperinflation and emphysema. High-resolution CT scans provide more detailed information.

- Arterial Blood Gases (ABG): Useful in severe cases to assess oxygen and carbon dioxide levels.

- Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Testing: Recommended for patients with early-onset disease or a family history of COPD.

- Six-Minute Walk Test: Evaluates exercise tolerance and oxygen desaturation.

Classification and Staging

COPD is classified based on airflow limitation (GOLD stages by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease):

- GOLD 1 (Mild): FEV₁ ≥ 80% predicted

- GOLD 2 (Moderate): FEV₁ 50–79%

- GOLD 3 (Severe): FEV₁ 30–49%

- GOLD 4 (Very Severe): FEV₁ < 30%

Further stratification considers symptom burden (using tools like the COPD Assessment Test [CAT] or the Modified Medical Research Council [mMRC] scale) and risk of exacerbations.

Management of COPD

Management aims to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, and slow disease progression. It involves a combination of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies.

Smoking Cessation

The single most effective intervention. Counseling, nicotine replacement therapies (patches, gums), and medications like bupropion and varenicline can support quitting.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Bronchodilators:

Short-acting (SABAs and SAMAs): For quick relief.

Long-acting (LABAs and LAMAs): For maintenance therapy.

Inhaled Corticosteroids (ICS):

Often used in combination with bronchodilators in patients with frequent exacerbations or eosinophilic inflammation.

Combination Inhalers:

LABA/LAMA or LABA/ICS for improved efficacy.

Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors (e.g., roflumilast):

For patients with chronic bronchitis and frequent exacerbations.

Mucolytics and Antibiotics:

Occasionally used for symptom control and during exacerbations.

Oxygen Therapy

For patients with chronic hypoxemia (PaO₂ < 55 mmHg or SpO₂ < 88%), long-term oxygen therapy can improve survival.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation

A comprehensive program including exercise training, nutritional counseling, and education. It improves exercise tolerance, reduces symptoms, and enhances quality of life.

Surgical and Interventional Procedures

- Lung Volume Reduction Surgery (LVRS): Removes diseased lung tissue to improve breathing mechanics.

- Bullectomy: Removes large bullae (air sacs) in patients with emphysema.

- Lung Transplantation: Option for selected patients with end-stage disease.

Lifestyle and Self-Management

- Exercise: Regular physical activity helps maintain lung function and muscle strength.

- Nutrition: Malnutrition is common; a high-protein, calorie-dense diet may be beneficial.

- Vaccinations: Influenza and pneumococcal vaccines reduce the risk of respiratory infections.

- Mental Health: Depression and anxiety are common and should be addressed.

Complications of COPD

- Respiratory Infections

- Pulmonary Hypertension

- Cor Pulmonale (right heart failure)

- Osteoporosis

- Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome

- Lung Cancer

- Depression and Cognitive Decline

Prognosis and Quality of Life

COPD is a chronic and progressive disease. Prognosis depends on the severity of airflow limitation, frequency of exacerbations, and presence of comorbid conditions. Although incurable, effective management can lead to improved symptom control and a better quality of life.

The BODE Index (Body mass index, Obstruction of airflow, Dyspnea, and Exercise capacity) is a multidimensional tool used to predict mortality.