Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a critical component of the craniofacial complex, facilitating essential functions such as mastication, speech, and facial expressions. This joint, unique in its dual articulation and complex biomechanics, is situated where the mandible (lower jaw) meets the temporal bone of the skull. Disorders of the TMJ can lead to significant discomfort and dysfunction, affecting quality of life and necessitating multidisciplinary management approaches. This article delves into the anatomy, physiology, pathology, and management of the TMJ, providing a comprehensive overview for medical, dental, and allied health professionals.

Table of Contents

ToggleAnatomy of the TMJ

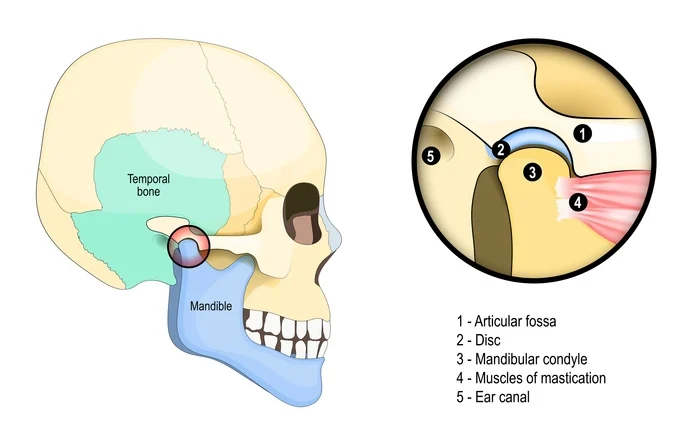

TMJ is formed by the articulation between:

- Mandibular Condyle: A rounded, convex bony structure at the top of the mandible.

- Glenoid (Mandibular) Fossa: A depression in the temporal bone.

- Articular Tubercle: Anterior to the glenoid fossa, it limits the forward movement of the mandibular condyle.

These bony elements provide the structural framework for joint movement, supported by cartilage and ligaments.

Articular Disc

Articular disc is a fibrocartilaginous structure dividing the joint into two compartments:

- Superior Compartment: Responsible for translational movements.

- Inferior Compartment: Facilitates rotational movements.

The disc is biconcave, with thicker anterior and posterior bands and a thinner intermediate zone. It acts as a cushion to distribute mechanical forces during jaw movements.

Ligaments

The TMJ is stabilized by:

- Capsular Ligament – Enclosing the joint, providing support, and maintaining synovial fluid within the joint space.

- Lateral Ligament – Preventing excessive lateral displacement.

- Accessory Ligaments – Including the sphenomandibular and stylomandibular ligaments, which provide additional stabilization.

Muscles of Mastication

The primary muscles influencing TMJ function are:

- Masseter – Elevates the mandible.

- Temporalis – Elevates and retracts the mandible.

- Medial Pterygoid – Assists in elevation and lateral movement.

- Lateral Pterygoid – Controls protrusion and depression of the mandible.

Innervation and Vascular Supply

- Innervation: The TMJ is primarily innervated by the auriculotemporal nerve, a branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (CN V).

- Vascular Supply: Arteries supplying the TMJ include branches of the external carotid artery, such as the superficial temporal and maxillary arteries.

Physiology of the TMJ

The TMJ is a highly specialized synovial joint that facilitates complex mandibular movements. The joint’s functionality is influenced by its unique structural design, coordinated muscle activity, and the lubrication provided by synovial fluid.

Mandibular Movements

- Rotation (Hinge Movement): This occurs in the inferior compartment of the joint and is the initial movement during mouth opening. The condyle rotates around a horizontal axis.

- Translation (Gliding Movement): This occurs in the superior compartment as the condyle and articular disc glide forward along the articular eminence. Translation is critical for full mouth opening.

- Protrusion and Retrusion: These movements involve the condyle sliding forward and backward, respectively, without rotation.

- Lateral Excursion: During lateral movement, one condyle pivots around a vertical axis while the other translates forward.

Role of Synovial Fluid

Synovial fluid within the TMJ serves two main functions:

- Lubrication – Reduces friction between articulating surfaces.

- Nutrition – Supplies nutrients to the avascular articular disc.

Neuromuscular Control

The TMJ is regulated by a sophisticated neuromuscular system:

- Sensory Input: Provided by mechanoreceptors and nociceptors in the joint capsule and surrounding structures.

- Motor Control: Coordinated by the central nervous system (CNS), ensuring synchronized activity of the muscles of mastication.

Functional Harmony

The TMJ works in conjunction with the dental occlusion and cranial structures. Any imbalance, such as malocclusion, can disrupt joint function, leading to temporomandibular disorders (TMD).

TMJ Disorders (TMD)

TMD encompasses a range of conditions affecting the joint, muscles, and surrounding structures. These disorders are categorized into:

- Myofascial Pain: Involving the muscles of mastication.

- Internal Derangement: Abnormal positioning of the articular disc.

- Arthritis: Inflammatory or degenerative changes within the joint.

- Other Disorders: Including trauma, ankylosis, or neoplasms.

Etiology

TMD can arise from:

- Trauma: Both direct (blunt force) and indirect (whiplash injuries) can lead to structural damage or functional disturbances in the TMJ.

- Malocclusion: Misalignment of teeth can create abnormal stress on the TMJ.

- Bruxism: Chronic clenching or grinding of teeth exerts excessive force on the TMJ and surrounding muscles.

- Psychological Stress: Stress-related habits, such as jaw clenching, contribute to muscular and joint strain.

- Systemic Conditions: Autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis can lead to inflammation and degeneration of the joint.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with TMD often report:

- Pain – Localized in the jaw, face, or extending to the neck and shoulders.

- Joint Sounds – Clicking, popping, or crepitus during jaw movement.

- Limited Jaw Mobility – Difficulty opening or closing the mouth, or episodes of jaw locking.

- Headaches – Often associated with muscle tension or referred pain.

- Ear Symptoms – Tinnitus, a feeling of fullness, or ear pain due to proximity to the ear structures.

Subtypes of TMD

- Muscle Disorders – Characterized by myalgia or myofascial pain.

- Joint Disorders – Including disc displacement with or without reduction, arthralgia, and degenerative joint disease.

- Combination Disorders – Involving both muscular and joint components.

Complications

If untreated, TMD can lead to chronic pain, restricted jaw movement, and secondary effects on adjacent structures, including the neck and shoulders.

Diagnosis

Clinical Examination

- History – Assess onset, duration, and associated symptoms.

- Palpation – Evaluate tenderness in the joint and surrounding muscles.

- Range of Motion – Measure mandibular opening and lateral movements.

- Auscultation – Listen for joint sounds.

Imaging

- X-ray – Baseline evaluation of bony structures.

- MRI – Visualizes soft tissue, including the articular disc.

- CT Scan – Provides detailed views of bony abnormalities.

- Ultrasound – Useful for dynamic imaging of the joint.

Diagnostic Criteria

The Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) provide a standardized framework for assessing and classifying TMD based on clinical findings and imaging.

Management of TMD

Conservative Treatments

- Patient Education: Counseling on avoiding habits like clenching or chewing gum.

- Physical Therapy: Exercises to strengthen and relax the jaw muscles.

- Medications: NSAIDs for pain and inflammation, Muscle relaxants, Tricyclic antidepressants for chronic pain

- Occlusal Splints: Custom devices to reduce bruxism and protect the joint.

Interventional Approaches

- Intra-articular Injections: Corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid to reduce inflammation and improve lubrication.

- Arthrocentesis: Flushing the joint to remove inflammatory mediators.

- Botulinum Toxin: Botox reduces muscle hyperactivity.

Surgical Options

Reserved for severe or refractory cases, surgical interventions include:

- Arthroscopy: Minimally invasive, used to visualize and treat joint pathology.

- Open Surgery: For structural abnormalities, such as disc repositioning or joint replacement.

- Total Joint Replacement (TJR): Indicated for advanced degenerative joint disease.

Emerging Therapies and Research

Recent advancements include:

- Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) – Promotes healing and regeneration.

- Stem Cell Therapy – Potential for cartilage repair.

- 3D Printing – Custom prosthetics for joint reconstruction.

Prevention and Long-Term Management

- Avoid excessive jaw movements.

- Address psychological stress through relaxation techniques or counseling.

- Maintain good posture to reduce strain on the jaw.

- Soft diet during acute phases.

- Avoiding hard or chewy foods.

- Regular follow ups to monitor joint health.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the common causes of TMJ disorders?

TMJ disorders can result from trauma, bruxism, malocclusion, stress-related habits, arthritis, or systemic conditions affecting joint health.

What are the symptoms of TMJ disorders?

Symptoms include jaw pain, clicking or popping sounds, difficulty opening or closing the mouth, headaches, ear pain, and jaw locking.

How is TMD diagnosed?

A diagnosis is made based on a patient’s history, clinical examination, and imaging techniques such as X-rays, MRI, or CT scans to assess joint structure and function.

What are the conservative treatments for TMD?

Non-invasive treatments include patient education, physical therapy, medications (NSAIDs, muscle relaxants), occlusal splints, and stress management.

When is surgery required for TMJ disorders?

Surgical intervention is considered for severe cases with persistent symptoms that do not respond to conservative treatments. Options include arthroscopy, disc repositioning, or total joint replacement.

Can TMJ disorders be prevented?

Preventive measures include avoiding excessive jaw movements, managing stress, maintaining good posture, and seeking early intervention for teeth grinding or misalignment.

How long does it take to recover from TMJ treatment?

Recovery time depends on the severity of the disorder and the treatment approach. Mild cases may resolve within weeks, while surgical recovery can take months.

Can lifestyle changes help manage TMJ disorders?

Yes, adopting a soft diet, avoiding hard or chewy foods, practicing relaxation techniques, and performing jaw exercises can help alleviate symptoms and improve function.

Conclusion

The temporomandibular joint is a pivotal structure that plays an integral role in daily functions. Understanding its complex anatomy and biomechanics is essential for diagnosing and managing disorders effectively. While conservative treatments remain the cornerstone of TMD management, advancements in imaging, pharmacology, and surgical techniques continue to enhance patient outcomes. Collaborative care among healthcare providers is key to addressing the multifactorial nature of TMJ disorders, ensuring comprehensive and personalized treatment strategies.