In dentistry, especially in the fields of oral surgery, periodontics, and implantology, suturing plays a critical role in promoting proper wound healing and ensuring favorable surgical outcomes. Suturing is not merely about closing a wound; it is a controlled process of approximating tissues in a way that restores function, minimizes infection risk, and improves esthetic results. At the heart of this process lies the suturing needle a precisely engineered instrument designed to carry and guide the suture material through delicate oral tissues.

Unlike medical suturing in general surgery, dentistry requires needles tailored to the unique environment of the oral cavity: restricted access, constant moisture, highly vascularized tissues, and esthetic considerations. Understanding the types, characteristics, and applications of suturing needles is essential for clinicians aiming to optimize patient care.

This article explores the design, classification, and selection criteria of suturing needles in dentistry. It also highlights which types are most commonly used in dental surgical procedures, their advantages, limitations, and clinical considerations.

Table of Contents

ToggleAnatomy of a Suturing Needle

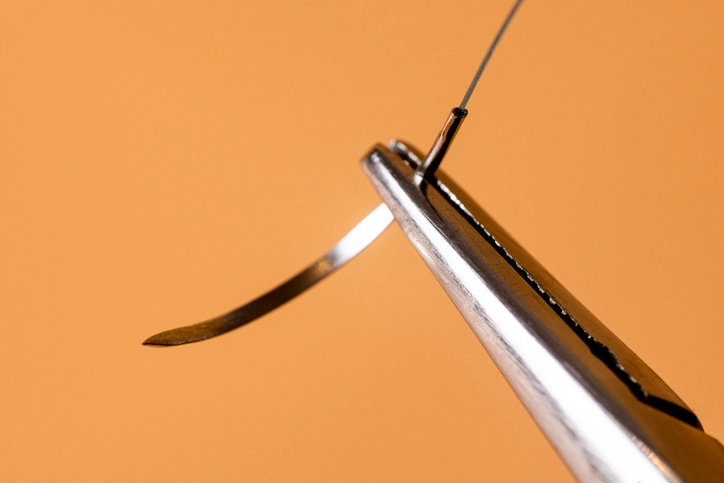

A suturing needle is a sophisticated tool that may appear simple but is precisely engineered for efficiency and minimal trauma. Its parts include:

1. Point (Tip)

- The sharp end that penetrates tissue.

- Determines how easily the needle enters and passes through tissue.

- Can be cutting, tapered, or blunt depending on design.

2. Body (Shaft)

- The main portion held by the needle holder.

- May be round, flattened, or triangular in cross-section.

- Shape influences tissue resistance and needle stability.

3. Swage (Attachment end)

- The part where the suture material is attached.

- Can be eyed (thread passed manually) or swaged (suture pre-attached to the needle).

- In dentistry, swaged needles are most common as they reduce trauma and minimize suture fraying.

Needle Curvature and Length

The oral cavity’s limited space necessitates the use of needles with specific curvatures and lengths to allow precision without excessive trauma.

Straight Needles: Rarely used in dentistry. Mostly applied in accessible areas outside the oral cavity.

Curved Needles: Classified by the fraction of a circle they represent:

1/4 Circle: Rarely used in oral surgery. Suitable for shallow tissues.

3/8 Circle: Very common in dentistry. Offers balance between access and ease of maneuvering.

1/2 Circle: Widely used in dental procedures, particularly in deeper areas like posterior oral cavity.

5/8 Circle: Useful in highly restricted spaces but less common.

Length of Needles: Dental needles are typically shorter than medical surgical needles, ranging from 8 mm to 19 mm, depending on the surgical site and tissue thickness.

Types of Needle Points

The type of point determines the degree of tissue trauma and penetration efficiency.

1. Cutting Needles

- Have a triangular cross-section with a sharp cutting edge.

- Designed for tough, fibrous tissues like oral mucosa.

Variants:

- Conventional Cutting Needle: Cutting edge on the inner curve.

- Reverse Cutting Needle: Cutting edge on the outer curve (preferred in dentistry to reduce suture pull-through and tissue tearing).

2. Taper Point Needles

- Rounded body that tapers to a sharp point.

- Spread tissues rather than cutting them.

- Used in delicate tissues like periosteum, submucosa, and vascular structures.

3. Blunt Point Needles

- Rounded, non-cutting tips.

- Used in friable tissues where cutting needles could cause tearing. Rare in dentistry.

4. Tapercut Needles

- Combination of taper and cutting design.

- Provide smooth penetration with cutting ability for dense tissues.

Materials and Manufacturing of Needles

Suturing needles are primarily made from high-quality stainless steel alloys due to their strength, flexibility, and resistance to corrosion in the oral environment. Features include:

- Strength: Must resist bending during insertion.

- Sharpness: Maintains penetration efficiency.

- Biocompatibility: Should not provoke tissue reaction.

- Surface Coating: Some needles are coated to enhance smooth passage and reduce drag.

Classification of Suturing Needles in Dentistry

Suturing needles used in dentistry can be classified based on several factors:

- By Shape of Curve: 3/8, 1/2, and 5/8 circle are most relevant.

- By Cross-Section: Cutting, reverse cutting, taper, tapercut.

- By Suture Attachment: Eyed vs. swaged (with swaged dominating dental practice).

- By Size: Ranging from very fine microsurgical needles (for periodontal or implant surgery) to standard sizes for oral mucosal closure.

Common Suturing Needles in Dentistry

Several specific needle designs are widely adopted in dental practice:

1. Reverse Cutting Needles (Most Common)

- Strong and sharp with the cutting edge on the convex side.

- Prevent suture tearing through fragile oral mucosa.

- Common sizes: 3/8 circle, 16–19 mm length.

Applications:

- Periodontal flap surgery

- Extraction site closure

- Implant surgeries

2. Taper Point Needles

- Useful when suturing delicate tissues (e.g., periosteum, graft materials).

- Less traumatic compared to cutting needles.

- Often smaller in size (11–13 mm).

3. Tapercut Needles

- Hybrid design suitable for denser tissues like gingiva or fibrotic mucosa.

- Provides penetration power with minimal tearing.

4. Microsurgical Needles

- Extremely fine needles (8–10 mm, often 6-0 to 8-0 sutures).

- Used in periodontal regenerative procedures, microsurgery, and esthetic gingival surgeries.

Applications in Dentistry

1. Periodontal Surgery

- Goal: Precise closure to promote primary intention healing.

- Preferred Needles: Reverse cutting, microsurgical taper point.

- Techniques: Interrupted sutures, sling sutures, vertical/horizontal mattress.

2. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Includes procedures like impacted tooth removal, cyst enucleation, and trauma repair.

- Preferred Needles: Reverse cutting (3/8 and 1/2 circle) for mucoperiosteal flaps.

3. Implant Surgery

- Requires tension-free closure to avoid dehiscence.

- Preferred Needles: Taper point or tapercut, especially for peri-implant mucosa.

4. Bone and Soft Tissue Grafting

- Microsurgical precision required.

- Preferred Needles: Microsurgical tapered needles with very fine suture material (6-0 to 8-0).

5. Pediatric Dentistry

- Shorter needles are favored due to smaller operative field.

- Typically, 3/8 circle reverse cutting needles with absorbable sutures.

Factors in Needle Selection

When choosing a suturing needle in dentistry, several factors must be considered:

Tissue Type

Mucosa requires cutting/reverse cutting.

Periosteum requires taper/tapercut.

Surgical Site Accessibility

Posterior regions may need 1/2 circle needles.

Anterior areas often allow 3/8 circle.

Suture Material

Needle size must match suture gauge (e.g., fine needles for 6-0 sutures).

Patient Considerations

Esthetics, healing capacity, systemic conditions.

Surgeon’s Skill and Preference

Comfort with handling certain needle curvatures or types.

Advantages of Proper Needle Selection

- Reduced tissue trauma

- Improved wound healing

- Secure knot placement

- Minimized risk of dehiscence or tearing

- Enhanced surgical precision and efficiency

Innovations in Dental Suturing Needles

Recent developments in needle technology include:

- Laser-sharpened points for minimal penetration resistance.

- Coated needles for smoother glide.

- Microsurgical designs to complement magnification-assisted procedures.

- Ergonomically swaged sutures for reduced needle-to-suture drag.

Sterility and Handling

- Needles are pre-sterilized and individually packaged.

- Must be handled with needle holders only—not fingers—to maintain sterility and sharpness.

- Disposal requires puncture-proof sharps containers.

Conclusion

Suturing needles are fundamental to dental surgery, serving as the conduit between suture material and oral tissues. In dentistry, the choice of needle is dictated by the unique challenges of the oral environment—limited access, fragile mucosa, and the need for esthetic, tension-free closures.

The reverse cutting needle remains the most widely used due to its ability to penetrate mucosa without tearing. However, taper and tapercut needles are indispensable for periosteal and graft-related procedures, while microsurgical needles have revolutionized periodontal and esthetic surgeries.

Ultimately, mastery of suturing in dentistry is not just about technical skills but also about understanding which needle to use, where, and why. With continued innovations in needle design and materials, clinicians are better equipped than ever to achieve predictable, minimally traumatic, and esthetically pleasing outcomes for their patients.