The mandible, commonly known as the lower jaw, is a vital component of the human craniofacial complex. It plays a pivotal role in various essential functions such as chewing, speaking, and maintaining the shape and aesthetics of the face. This article delves into the comprehensive exploration of the mandible, including its anatomy, function, developmental aspects, and clinical significance.

Table of Contents

ToggleAnatomy of the Mandible

Structure

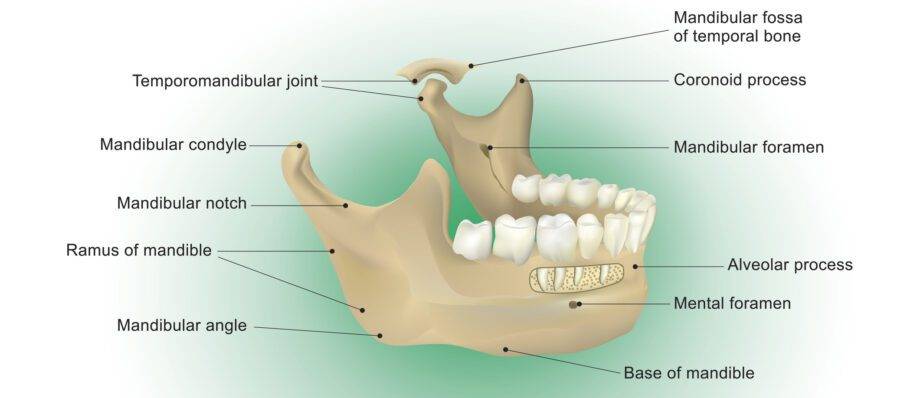

The mandible is the largest and strongest bone in the human face. It is a horseshoe-shaped bone that forms the lower jaw and consists of a body, two rami (singular: ramus), and a variety of anatomical features.

The Body

The body of the mandible is the horizontal, U-shaped portion that extends from the chin to the area just in front of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). The body forms the majority of the mandible and contains the alveolar processes, which house the lower teeth.

The Rami

Each ramus of the mandible extends vertically from the posterior ends of the mandibular body. These rami are located on either side of the face and are essential for various functional aspects, such as attachment points for muscles involved in chewing.

Foramen

The mandible features several important foramina, or openings. Of particular significance are the mandibular foramen, located on the inner side of each ramus. The mandibular foramen allows for the passage of the inferior alveolar nerve, which supplies sensation to the lower teeth and jaw.

Condyle

The condyle of the mandible is a rounded prominence at the posterior end of each ramus. It forms the articulation point with the temporal bone at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), allowing for the pivotal function of opening and closing the mouth.

Coronoid Process

The coronoid process is another feature on the ramus of the mandible, and it serves as an attachment point for the temporalis muscle. This muscle is essential for the closing and retracting of the jaw during chewing.

Articulation

The mandible articulates with several other cranial and facial bones, forming a complex system that allows for various functions and movements:

Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)

The articulation between the mandible and the temporal bone of the skull is known as the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). This joint enables the mandible to move in various directions, including opening, closing, sliding, and rotating. The TMJ is surrounded by a joint capsule and a disc of fibrocartilage, allowing for smooth, painless movement.

Hyoid Bone

The mandible also indirectly articulates with the hyoid bone, a U-shaped bone located in the neck. The hyoid bone plays a crucial role in swallowing and speech.

Function of the Mandible

- Mastication

- Speech and Articulation

- Aesthetics

Mastication

The primary function of the mandible is to enable the process of mastication, which is the mechanical breakdown of food into smaller, digestible particles. This function is critical for the digestion and absorption of nutrients. The mandible’s movement in chewing involves complex interactions with the muscles, teeth, and other craniofacial structures.

Speech and Articulation

The mandible is an integral part of the speech apparatus. It contributes to the articulation of sounds by facilitating the precise movements of the tongue, lips, and other oral structures during speech production.

Aesthetics

The mandible plays a significant role in the aesthetics of the face. It provides support for the soft tissues of the lower face, and its shape and position greatly influence an individual’s facial appearance.

Development of the Mandible

- Embryonic Development

- Growth and Development in Childhood

- Aging and Changes

Embryonic Development

The mandible has an intriguing developmental history. It forms from the first pharyngeal arch during embryogenesis, which also gives rise to other important structures like the maxilla, part of the ear, and various muscles. The initial mandibular arch appears during the fourth week of embryonic development, and it gradually differentiates into the mandible we recognize in adults.

Growth and Development in Childhood

The mandible undergoes significant growth and development during childhood and adolescence. The primary centers of growth are located at the condyle and the symphysis (midline fusion) of the mandible. Hormonal changes during puberty can influence the growth and development of the mandible.

Aging and Changes

As a person ages, the mandible continues to change. Bone remodeling and resorption occur over time, which can lead to changes in the shape and position of the mandible. These changes may be observed as part of the natural aging process.

Clinical Significance

- Dental Health

- Temporomandibular Joint Disorders (TMD)

- Trauma and Fractures

- Orthodontics and Jaw Surgery

- Aesthetic Surgery

- Speech Therapy

Dental Health

The health of the mandible is closely linked to dental health. The alveolar processes in the mandible house the lower teeth, and maintaining good oral hygiene is crucial to prevent issues like tooth decay and gum disease that can affect the bone and surrounding tissues.

Temporomandibular Joint Disorders (TMD)

Problems with the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) can result in temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD). These disorders can cause jaw pain, clicking or popping sounds, limited jaw movement, and other symptoms that can significantly impact a person’s quality of life.

Trauma and Fractures

The mandible is susceptible to trauma and fractures, often resulting from accidents, falls, or physical altercations. Mandibular fractures can have a range of clinical presentations and may require surgical intervention to restore proper function and aesthetics.

Orthodontics and Jaw Surgery

Orthodontic treatment often involves adjusting the position of the mandible to correct bite issues such as overbites, underbites, and crossbites. In some cases, orthodontic treatment may be combined with orthognathic surgery to reposition the mandible for optimal function and aesthetics.

Aesthetic Surgery

Aesthetic surgery, including procedures such as genioplasty (chin surgery), can involve the manipulation of the mandible to enhance facial aesthetics. These surgeries are often performed to improve the overall balance and harmony of the face.

Speech Therapy

Speech therapists may work with individuals who have speech and articulation difficulties related to the mandible. Therapy can help improve speech patterns and oral motor coordination.

Arteries Associated with the Mandible

To perform these functions, the mandible requires a network of arteries to provide it with nutrients and oxygen. The primary arteries associated with the mandible are the inferior alveolar artery, the mental artery, and the submental artery.

- Inferior Alveolar Artery

- Mental Artery

- Submental Artery

Inferior Alveolar Artery

The inferior alveolar artery is a branch of the maxillary artery, which, in turn, is a branch of the external carotid artery. The external carotid artery is one of the two main arteries supplying blood to the face and neck.

The inferior alveolar artery descends through the mandibular foramen, an opening in the mandible, and enters the mandibular canal, which runs through the body of the mandible.

Inside the mandibular canal, this artery provides blood supply to the lower teeth, gingiva (gums), and the lower part of the mandible itself.

Mental Artery

The mental artery is a branch of the inferior alveolar artery within the mandibular canal.

After emerging from the mandibular foramen, the mental artery exits the mental foramen, located on the outer surface of the mandible, just below the lower lip.

The mental artery supplies blood to the chin, lower lip, and some surrounding facial tissues.

Submental Artery

The submental artery is another branch of the facial artery, which itself is a branch of the external carotid artery.

This artery runs beneath the mandible’s body, parallel to the midline, and supplies blood to the chin, the muscles of the lower lip, and the submental region.

Muscles Associated with the Mandible

The mandible, or lower jawbone, is home to several muscles that are crucial for various functions such as chewing, speaking, and facial expressions. These muscles play an essential role in the mobility and stability of the mandible and, by extension, the entire face. Here are some of the key muscles associated with the mandible:

- Masseter Muscle

- Temporalis Muscle

- Medial Pterygoid Muscle

- Lateral Pterygoid Muscle

- Digastric Muscle

- Mylohyoid Muscle

Masseter Muscle

The masseter is one of the most prominent muscles in the jaw region and is often referred to as the “jaw muscle.”

It originates from the zygomatic arch (cheekbone) and inserts into the mandible’s angle and ramus.

The masseter is a powerful muscle responsible for elevating the mandible, closing the jaw during chewing, and providing the force needed for efficient mastication (chewing).

Temporalis Muscle

The temporalis muscle is located on the sides of the head, covering the temporal bone. It inserts onto the coronoid process of the mandible.

The temporalis muscle is essential for jaw closure and helps with the retraction of the mandible.

Medial Pterygoid Muscle

The medial pterygoid muscle is situated deep within the oral cavity, just behind the mandible. It originates from the sphenoid bone and the maxillary tuberosity and inserts into the mandible’s angle.

The medial pterygoid muscle assists in elevating and closing the jaw, as well as moving it from side to side during chewing.

Lateral Pterygoid Muscle

The lateral pterygoid muscle is another deep muscle located in the region of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). It has two heads: the superior head and the inferior head.

The lateral pterygoid muscle is primarily responsible for opening the jaw. When it contracts, it pulls the head of the mandible forward and allows the mouth to open. It also plays a role in moving the jaw from side to side.

Digastric Muscle

The digastric muscle is a muscle with two bellies connected by an intermediate tendon. The anterior belly originates from the digastric fossa of the mandible, while the posterior belly arises from the mastoid notch of the temporal bone.

The digastric muscle is involved in opening the mouth by depressing the mandible. It also helps with swallowing by stabilizing the hyoid bone.

Mylohyoid Muscle

The mylohyoid muscle is a thin, flat muscle that forms the floor of the mouth. It originates from the mylohyoid line on the mandible and inserts into the midline raphe, which stretches from the mandible to the hyoid bone.

The mylohyoid muscle assists in various functions, including swallowing, speaking, and raising the floor of the mouth during certain oral actions.

These muscles work in coordination to facilitate the movement and function of the mandible. They enable actions like opening and closing the mouth, chewing food, speaking, and controlling the lower facial expressions. The mandibular muscles are innervated by the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) and are crucial for the overall oral and facial functionality. Disruptions in the function of these muscles can lead to various issues, including problems with eating, speaking, and overall oral health.

Mandibular Nerves

Mandibular nerves refer to a group of nerves that play a significant role in the innervation of the lower face, including the mandible (lower jaw), and the muscles associated with it. These nerves are primarily branches of the trigeminal nerve, which is the fifth cranial nerve (CN V). The trigeminal nerve is responsible for providing sensory and motor functions to the face, as well as controlling the muscles used for chewing. The mandibular nerves include the following main branches:

- Inferior Alveolar Nerve

- Mental Nerve

- Buccal Nerve

- Auriculotemporal Nerve

- Lingual Nerve

Inferior Alveolar Nerve

The inferior alveolar nerve is one of the main branches of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. It runs through the mandibular foramen, which is an opening in the mandible, and enters the mandibular canal to supply the lower teeth, gums, and the lower lip.

It provides sensory innervation to the teeth and mucous membranes in the lower jaw. It also carries pain and temperature sensations from this region.

Mental Nerve

The mental nerve is a branch of the inferior alveolar nerve, and it exits the mandible through the mental foramen, located on the external surface of the lower jaw.

This nerve provides sensory innervation to the chin, lower lip, and the mucous membranes of the lower lip and gums. It is responsible for touch, temperature, and pain sensations in these areas.

Buccal Nerve

The buccal nerve is another branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. It provides sensory innervation to the buccal (cheek) region, including the skin, mucous membranes, and the buccal gingiva (gums) on the outer aspect of the lower molars. It carries sensory information related to touch, temperature, and pain in this area.

Auriculotemporal Nerve

The auriculotemporal nerve is a branch of the mandibular nerve that provides sensory innervation to the temporal region of the scalp and the external ear.

It also carries parasympathetic fibers to the parotid gland, a salivary gland located in front of the ear.

Lingual Nerve

The lingual nerve is another branch of the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. It provides sensory innervation to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, the floor of the mouth, and the lingual gingiva (gums) on the lower jaw.

The lingual nerve is responsible for transmitting taste and other sensory information from these areas.

In addition to their sensory functions, the mandibular nerves play a role in motor functions by supplying some of the muscles used for chewing (mastication). These motor branches are involved in controlling the movements of the muscles of mastication, including the masseter, temporalis, and pterygoid muscles.

Conclusion

The mandible is a remarkable and multifaceted bone that plays a central role in the structure, function, and clinical significance of the human craniofacial complex. Its significance in chewing, speech, and aesthetics makes it an integral part of daily life. Understanding the anatomy, function, development, and clinical implications of the mandible is essential for healthcare professionals, researchers, and anyone interested in the intricacies of human anatomy.