Ludwig’s angina is a rapidly progressive, potentially life-threatening cellulitis of the floor of the mouth. It involves the submandibular, sublingual, and submental spaces bilaterally and typically arises from odontogenic infections. Despite its name, Ludwig’s angina is not a form of angina pectoris. First described in 1836 by the German physician Wilhelm Friedrich von Ludwig, it continues to be a significant medical emergency even in the modern era of antibiotics.

This article explores the clinical entity of Ludwig’s angina in detail, addressing its etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approaches, therapeutic management, and outcomes.

Table of Contents

ToggleHistorical Background

Wilhelm von Ludwig first described this disease in 1836, identifying it as a gangrenous cellulitis involving the tissues of the neck and floor of the mouth. At the time, the condition was often fatal due to the lack of antibiotics and effective airway management. With advances in medical knowledge, antibiotics, imaging, and surgical techniques, mortality has decreased substantially, yet it remains a condition requiring immediate attention.

Anatomy Relevant to Ludwig’s Angina

Understanding the anatomical basis of Ludwig’s angina is crucial. The submandibular space, divided by the mylohyoid muscle into sublingual (above) and submylohyoid (below) compartments, serves as the central location for the infection. The fascial planes of the neck facilitate the rapid spread of infection into adjacent spaces, such as:

- Submental space: Anteriorly beneath the chin

- Parapharyngeal space: Lateral extension, potentially affecting the airway

- Retropharyngeal space: Posteriorly, which can descend into the mediastinum, leading to mediastinitis

The lack of anatomical barriers between these compartments allows for diffuse spread, making the condition particularly dangerous.

Etiology

The etiology of Ludwig’s angina refers to the origin and causes of the infection. It is essential to understand the conditions and risk factors that predispose individuals to this dangerous cellulitis, as well as the specific microorganisms that contribute to the disease process.

1. Odontogenic Infections (Primary Cause)

The most common and significant source of Ludwig’s angina is odontogenic infection, which originates from infected teeth or supporting dental structures. Studies report that 70–90% of cases can be traced back to a dental origin, especially from the second and third mandibular molars. These teeth have long roots that extend below the insertion of the mylohyoid muscle, allowing dental infections to spread directly into the submandibular space.

Common dental causes include:

- Periapical abscesses: Infection of the tooth pulp that spreads to the apex of the root

- Periodontal disease: Inflammation and infection of the gums and supporting structures of the teeth

- Pericoronitis: Infection of the gum tissue surrounding a partially erupted molar, often a wisdom tooth

- Post-extraction infections: Infections occurring after tooth removal, especially in non-sterile or improperly managed wounds

2. Non-Odontogenic Causes

Although less common, Ludwig’s angina can also originate from infections or trauma unrelated to dental pathology. These include:

a. Salivary Gland Infections (Sialadenitis)

Infections of the submandibular salivary glands, particularly sialadenitis, can spread to surrounding tissues. Blockage of the salivary duct (e.g., by a stone or calculus) creates a fertile environment for bacterial overgrowth and secondary cellulitis.

b. Trauma and Iatrogenic Injury

Trauma to the oral cavity, whether accidental or surgical, may introduce pathogens into deep tissues:

- Oral or facial lacerations

- Poorly performed or unsanitary oral piercings

- Injuries during dental procedures (e.g., injections, extractions)

- Endotracheal intubation trauma in rare cases

c. Tonsillar and Pharyngeal Infections

While infections such as tonsillitis or peritonsillar abscess usually remain localized, they can occasionally spread into the submandibular and parapharyngeal spaces and cause Ludwig’s angina. This route is more common in pediatric patients.

d. Mandibular Fractures

Compound or open fractures of the jaw, especially when complicated by oral contamination, may lead to deep tissue infections that mimic or evolve into Ludwig’s angina.

e. Foreign Bodies

Sharp or contaminated foreign objects (e.g., toothpicks, fish bones) accidentally embedded in the oral mucosa can breach tissue planes and initiate infection if not promptly removed.

f. Infections of the Floor of the Mouth

Conditions like ranulas (mucous retention cysts) or mucoceles can become secondarily infected, leading to a deep tissue infection if untreated.

3. Risk Factors and Predisposing Conditions

Certain health conditions increase a person’s susceptibility to Ludwig’s angina, either by impairing immunity, delaying wound healing, or increasing microbial load in the oral cavity:

a. Diabetes Mellitus

Uncontrolled diabetes impairs neutrophil function and reduces tissue perfusion, leading to more aggressive infections and poor healing. Diabetic ketoacidosis also provides a favorable environment for anaerobic bacteria.

b. Immunocompromised States

Patients with weakened immune systems are at higher risk for severe infections. These include:

- HIV/AIDS

- Cancer (especially head and neck cancers)

- Chemotherapy or radiotherapy patients

- Long-term corticosteroid use

- Post-transplant patients on immunosuppressants

c. Poor Oral Hygiene and Dental Care

Lack of access to dental services, neglected dental health, and poor hygiene contribute to the chronic presence of oral infections and increase the likelihood of cellulitis spreading into the neck.

d. Malnutrition

Malnourished individuals have weakened immune responses and are more prone to infections spreading rapidly.

e. Substance Abuse

Chronic alcohol use and smoking are associated with poor oral health, mucosal trauma, and delayed healing, all of which contribute to Ludwig’s angina risk.

4. Microbiological Etiology

Ludwig’s angina is typically a polymicrobial infection involving aerobic and anaerobic bacteria that are part of the normal flora of the oral cavity. The synergistic action of these organisms enhances tissue destruction and facilitates rapid spread.

a. Aerobic Bacteria

- Streptococcus viridans group: These gram-positive cocci are part of the normal flora of the mouth and are commonly implicated in odontogenic infections.

- Staphylococcus aureus (including MRSA strains): Less common but more severe in immunocompromised patients or in healthcare-associated infections.

- Enterobacteriaceae: Occasionally isolated, especially in diabetic or hospitalized patients.

b. Anaerobic Bacteria

Anaerobes are crucial contributors to Ludwig’s angina due to their ability to thrive in necrotic, hypoxic environments:

- Fusobacterium nucleatum and Fusobacterium necrophorum

- Bacteroides fragilis

- Prevotella melaninogenica

- Peptostreptococcus species

These bacteria produce enzymes like collagenase and hyaluronidase, which break down connective tissue and facilitate the rapid spread of infection.

c. Resistance Patterns

Antibiotic resistance is increasingly observed in oral flora, particularly in anaerobes and MRSA. Hence, culture and sensitivity testing remain vital for guiding targeted therapy.

Summary Table: Etiologic Factors in Ludwig’s Angina

| Category | Specific Examples |

|---|---|

| Odontogenic | Infected molars, periapical abscess, pericoronitis |

| Salivary Gland Infections | Submandibular sialadenitis, duct obstruction |

| Trauma/Iatrogenic | Oral piercings, dental procedures, intubation injuries |

| Pharyngeal Infections | Tonsillitis, peritonsillar abscess |

| Mandibular Fractures | Open jaw injuries with contamination |

| Foreign Bodies | Fish bones, toothpicks |

| Systemic Risk Factors | Diabetes, HIV, cancer, immunosuppression |

| Microorganisms (Aerobic) | Strep. viridans, Staph. aureus |

| Microorganisms (Anaerobic) | Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides |

Pathophysiology

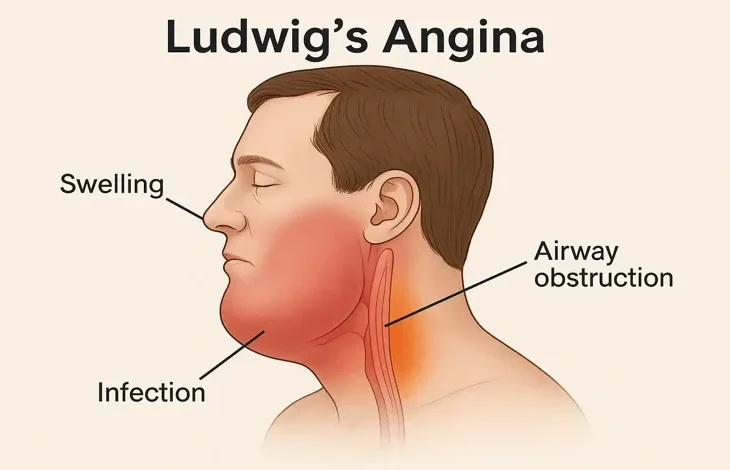

The pathophysiology of Ludwig’s angina is characterized by a rapidly progressing infection of the submandibular space, leading to severe tissue inflammation, edema, and potential airway obstruction. Understanding this pathophysiology requires an appreciation of the anatomy of the head and neck, the behavior of the infectious organisms, and the body’s inflammatory response.

1. Initial Infection and Portal of Entry

Ludwig’s angina typically begins with an odontogenic infection, most commonly originating from the second or third mandibular molars. The roots of these molars extend below the mylohyoid muscle, which separates the sublingual space (above) from the submylohyoid or submaxillary space (below). Because of this anatomical relationship, infections in these teeth have direct access to the submandibular space.

Other portals of entry include:

- Salivary gland ducts (especially the Wharton’s duct of the submandibular gland)

- Traumatic breaches of the oral mucosa

- Spread from adjacent fascial spaces

Once bacteria gain entry, they proliferate and incite an acute inflammatory response.

2. Inflammation and Tissue Response

The initial host response to bacterial invasion is characterized by:

- Release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1, TNF-α, IL-6)

- Neutrophil infiltration into the infected tissues

- Vasodilation and increased vascular permeability

These changes result in:

- Edema and induration of the submandibular and sublingual spaces

- Erythema and warmth of the skin overlying the infected area

- Pain due to pressure on nerve endings and tissue tension

Importantly, Ludwig’s angina is generally not associated with early abscess formation. Instead, it presents as a diffuse cellulitis a key clinical distinction. The infected area becomes firm and “woody” due to widespread edema and inflammatory infiltration of the fascial and muscular tissues.

3. Anatomical Spread of Infection

The neck contains a series of fascial planes and compartments that facilitate the rapid and unrestricted spread of infection. Ludwig’s angina involves bilateral spread through the following spaces:

a. Sublingual Space

- Located above the mylohyoid muscle

- Involvement here causes elevation and posterior displacement of the tongue, contributing to airway obstruction

b. Submylohyoid (Submaxillary) Space

- Located below the mylohyoid muscle

- Involvement leads to swelling under the mandible and in the neck

c. Submental Space

- Located between the anterior bellies of the digastric muscles, below the chin

- Infection from either submandibular space can extend anteriorly into this compartment

d. Parapharyngeal and Retropharyngeal Spaces

- Infection may spread laterally and posteriorly into the parapharyngeal space, which is adjacent to the carotid sheath

- The retropharyngeal space extends from the skull base to the mediastinum, allowing infection to descend into the chest, leading to mediastinitis, a potentially fatal complication

e. Pretracheal and Danger Space

The “danger space” (between the alar and prevertebral fascia) is particularly concerning because it provides a direct conduit from the neck into the posterior mediastinum

4. Airway Obstruction

The most feared and immediate complication of Ludwig’s angina is airway compromise, resulting from several simultaneous pathological events:

- Tongue elevation and posterior displacement, obstructing the oropharyngeal inlet

- Edema of the floor of the mouth and pharynx, narrowing the airway

- Trismus (inability to open the jaw) may prevent oral intubation

- Laryngeal edema and spasm in advanced cases

Airway obstruction may develop suddenly and unpredictably, making early and proactive airway management essential. This is a key reason Ludwig’s angina is treated as a surgical and airway emergency.

5. Microbial Synergism and Toxin Production

The polymicrobial nature of Ludwig’s angina plays a vital role in its pathophysiology. Anaerobic and facultative bacteria work in concert to promote tissue invasion and destruction:

- Anaerobic bacteria (e.g., Fusobacterium, Bacteroides) produce proteolytic enzymes such as collagenases and hyaluronidases that degrade connective tissue

- Facultative anaerobes (e.g., Streptococcus viridans) can thrive in both oxygenated and anaerobic environments, facilitating deeper spread

- Some bacteria release endotoxins and exotoxins, exacerbating the local inflammatory response and contributing to systemic symptoms

This microbial synergy is particularly dangerous in poorly perfused tissues, where immune surveillance and antibiotic penetration are reduced.

6. Systemic Inflammatory Response and Sepsis

As the local infection progresses, bacteria and inflammatory mediators can enter the systemic circulation, leading to:

- Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS)

- Sepsis

- Septic shock in severe or untreated cases

The cascade of cytokine release can lead to:

- Hypotension

- Tachycardia

- High or low body temperature

- Altered mental status

- Multi-organ dysfunction

Patients with diabetes mellitus, renal failure, HIV/AIDS, or malignancy are especially prone to severe systemic effects due to impaired immune function.

7. Progression Without Pus Formation

One hallmark of Ludwig’s angina is that it is often a cellulitis without a well-defined abscess, especially in the early stages. This poses several challenges:

- Difficulty in identifying clear fluid collections on imaging

- Ineffectiveness of surgical drainage in the absence of loculated pus

- Delayed recognition of severity due to the absence of classic abscess signs

However, as the disease progresses or secondary bacterial strains accumulate, liquefaction necrosis and pus formation may occur, necessitating surgical debridement and drainage.

8. Impact of Comorbid Conditions

Certain underlying conditions can dramatically influence the pathophysiological course:

a. Diabetes Mellitus

- Impairs neutrophil chemotaxis and phagocytosis

- Increases risk of rapid tissue necrosis and systemic dissemination

- Promotes glucose-rich environment conducive to bacterial growth

b. HIV/AIDS and Immunodeficiency

- Impairs cellular immunity, increasing susceptibility to atypical organisms

- Delays resolution of infection and increases likelihood of complications

c. Malnutrition

Reduces host defenses and tissue repair capability

Schematic Overview of Pathophysiological Process

- Portal of Entry

→ Odontogenic infection or trauma breaches mucosal barrier Bacterial Proliferation

→ Polymicrobial synergy causes deep tissue invasionInflammatory Response

→ Cytokine release, neutrophil recruitment, edemaAnatomical Spread

→ Infection moves bilaterally through submandibular, submental, and sublingual spacesAirway Compromise

→ Tongue elevation + pharyngeal swelling = respiratory distressSystemic Effects

→ Bacteremia, sepsis, organ dysfunctionPossible Complications

→ Abscess formation, mediastinitis, septic shock, death

Clinical Presentation

Ludwig’s angina typically presents abruptly and progresses rapidly over hours. Key clinical features include:

Local Symptoms

- Submandibular swelling and induration (often “woody” and firm)

- Bilateral involvement (a defining feature)

- Pain in the floor of the mouth

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Difficulty speaking (dysarthria)

- Drooling due to inability to swallow saliva

- Trismus (limited mouth opening)

Systemic Symptoms

- Fever and chills

- Malaise

- Tachycardia

- Signs of sepsis in advanced stages

Airway Compromise

One of the most feared complications, airway compromise, can present with:

- Stridor

- Respiratory distress

- Cyanosis

- Anxiety and restlessness

- Elevated tongue obstructing the oropharynx

Diagnosis

Clinical Diagnosis

The diagnosis is primarily clinical, based on characteristic symptoms and physical findings. However, prompt imaging and laboratory studies are essential for confirming the diagnosis and assessing complications.

Imaging Studies

- CT scan with contrast: The gold standard for evaluating deep neck infections. It can delineate the extent of soft tissue involvement and identify abscesses if present.

- MRI: Provides excellent soft tissue detail but is less commonly used due to limited availability in emergency settings.

- Ultrasound: Useful in guiding drainage or identifying fluid collections, though it is operator-dependent and less reliable for deep neck spaces.

Laboratory Tests

- Complete blood count (CBC): Often shows leukocytosis

- Blood cultures: To detect bacteremia

- C-reactive protein (CRP) and ESR: Elevated in systemic inflammation

- Cultures from surgical specimens or aspirates

Differential Diagnosis

Several other conditions may mimic Ludwig’s angina, and it is essential to distinguish between them:

- Peritonsillar abscess

- Retropharyngeal abscess

- Angioneurotic edema (hereditary or allergic)

- Epiglottitis

- Tumors of the neck or oral cavity

- Submandibular sialadenitis

Management

The management of Ludwig’s angina is a true medical and surgical emergency requiring prompt, aggressive, and multidisciplinary intervention. The priorities in managing this condition are:

- Securing the airway

- Administering empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Surgical intervention when necessary

- Supportive care and monitoring

- Addressing the source of infection

- Managing comorbid conditions

1. Airway Management: The First and Foremost Priority

The potential for sudden airway obstruction is the most critical concern in Ludwig’s angina. Airway management must be addressed early and proactively, often before signs of respiratory distress are fully apparent.

a. Indications for Airway Intervention

- Stridor, muffled voice (“hot potato voice”)

- Respiratory distress or tachypnea

- Inability to handle oral secretions or drooling

- Cyanosis or hypoxia

- Progressive neck swelling and tongue elevation

- Trismus (limited mouth opening)

b. Airway Management Techniques

- Awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation: Preferred in cooperative patients without severe swelling; allows for visualized, controlled placement while maintaining spontaneous breathing.

- Video laryngoscopy: Useful but limited if mouth opening is restricted or edema distorts landmarks.

- Tracheostomy: Often the safest and most definitive airway in severe or rapidly progressing cases. Elective tracheostomy should be performed early if intubation appears unsafe or likely to fail.

- Cricothyrotomy: Emergency option if neither intubation nor tracheostomy can be performed rapidly; not ideal due to infection risk in distorted anatomy.

Key Point: Airway compromise can deteriorate within minutes. Proactive airway management in a controlled setting (OR or ICU) is vastly preferable to emergency intervention during a crisis.

2. Empiric Antibiotic Therapy

Once the airway is secured or closely monitored, immediate administration of empiric intravenous antibiotics is critical to halt the infection’s progression.

a. Empiric Coverage

Given the polymicrobial nature of Ludwig’s angina (aerobic and anaerobic flora), antibiotics should cover:

- Gram-positive cocci (e.g., Streptococcus, Staphylococcus)

- Anaerobes (e.g., Bacteroides, Fusobacterium)

- Occasionally gram-negative bacilli, especially in diabetic or hospitalized patients

b. Recommended Initial Regimens

- Ampicillin-sulbactam (Unasyn) IV

- Clindamycin IV (especially in penicillin-allergic patients)

- Piperacillin-tazobactam (Zosyn) IV

- Meropenem or imipenem IV in severe or resistant cases

- Vancomycin: Add if MRSA is suspected, especially in healthcare-associated or immunocompromised settings

c. Duration of Therapy

- Typically 2–3 weeks, starting with IV antibiotics and transitioning to oral antibiotics once clinical improvement occurs

- Guided by clinical response and imaging

- Culture-directed therapy should replace empiric antibiotics once results are available

3. Surgical Management

While early Ludwig’s angina may respond to antibiotics alone, surgical intervention becomes necessary in many cases, especially when:

- There is abscess formation (as seen on imaging or exam)

- The patient deteriorates or fails to improve after 24–48 hours of antibiotics

- There is extensive necrotic tissue or gas-forming infection

- Airway compromise requires operative airway access

a. Surgical Techniques

- Incision and drainage (I&D) of the submandibular, sublingual, and submental spaces via external cervical incisions

- Intraoral drainage through the floor of the mouth (when feasible)

- Wide and dependent drainage is essential due to the diffuse nature of the cellulitis

- Debridement of necrotic tissue

- Removal of the source of infection (e.g., infected molar tooth extraction)

b. Drain Placement

After surgical drainage, soft rubber or Penrose drains are usually placed to allow ongoing discharge of inflammatory fluid and prevent re-accumulation.

4. Supportive and Critical Care

Patients with Ludwig’s angina often require intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring, particularly if systemic illness, airway instability, or sepsis is present.

a. Monitoring

- Continuous oxygen saturation and respiratory rate

- Hemodynamic stability (blood pressure, heart rate)

- Neurologic status, especially in patients with sepsis or altered mental status

b. Fluid and Electrolyte Management

- Aggressive IV hydration is needed to maintain perfusion and support immune function

- Electrolyte imbalances should be corrected

c. Pain Control and Antipyretics

- NSAIDs or opioids are often required

- Fever should be treated to improve comfort and reduce metabolic demand

d. Nutritional Support

- Many patients are unable to eat due to trismus, swelling, or intubation

- Nutrition may be provided via nasogastric tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) if prolonged

5. Dental and Source Control

In odontogenic Ludwig’s angina, removing the infected tooth is a critical component of treatment. This often involves:

- Tooth extraction (commonly of second or third molars)

- Debridement of infected periodontal tissues

- Oral surgery consultation

Delaying dental source control increases the risk of persistent or recurrent infection.

6. Adjunctive Therapies (Controversial)

Some additional therapies have been explored but remain controversial or case-dependent:

a. Corticosteroids

- May reduce airway edema and inflammation

- Evidence is limited; use is individualized

- Risks include immunosuppression and masking signs of worsening infection

b. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT)

- Proposed to help in necrotizing infections and anaerobic bacterial growth

- Rarely used due to logistical constraints and lack of strong evidence

7. Multidisciplinary Approach

Effective management requires coordination between:

- Otolaryngologists (ENT specialists) or oral and maxillofacial surgeons for drainage and airway evaluation

- Anesthesiologists for airway management planning

- Critical care physicians for ICU management

- Dentists or oral surgeons for definitive source control

- Infectious disease specialists for antibiotic stewardship

- Radiologists for timely and accurate imaging

8. Follow-Up and Rehabilitation

Even after resolution of the acute infection, patients may require:

- Wound care and drain management

- Physical therapy to improve jaw mobility (trismus relief)

- Dental rehabilitation or prosthetic planning

- Glycemic control and management of comorbidities

Long-term follow-up ensures resolution and prevents recurrence.

Summary Table: Key Elements of Ludwig’s Angina Management

| Management Area | Actions |

|---|---|

| Airway | Early intubation, tracheostomy if needed |

| Antibiotics | IV broad-spectrum, culture-directed therapy |

| Surgery | I&D, debridement, drain placement, tooth extraction |

| Supportive Care | ICU monitoring, hydration, pain control, nutritional support |

| Multidisciplinary Team | ENT, anesthesiology, ICU, dentistry, infectious disease |

| Follow-Up | Dental rehabilitation, physical therapy, wound care |

Complications

Ludwig’s angina, though rare in the antibiotic era, remains a high-risk and life-threatening infection of the submandibular and sublingual spaces. If not promptly and aggressively managed, the condition can lead to a cascade of complications, ranging from airway obstruction to systemic sepsis and multi-organ failure.

Complications arise due to the rapid progression, fascial space involvement, and polymicrobial virulence. Some complications develop acutely within hours, while others emerge later, even after initial treatment.

I. Airway Obstruction

a. Mechanism

- Progressive edema of the sublingual and submandibular spaces causes tongue elevation, posterior displacement, and compression of the oropharynx.

- The floor of the mouth becomes indurated and swollen, narrowing the airway.

- Pharyngeal and laryngeal edema may also develop, further compromising airflow.

b. Consequences

- Sudden respiratory failure

- Hypoxia and hypercapnia

- Cardiac arrest if unrecognized or untreated

- Airway obstruction is the leading cause of early mortality in Ludwig’s angina and the primary reason for early airway management.

II. Descending Necrotizing Mediastinitis (DNM)

a. Mechanism

- The infection may track from the neck down through the retropharyngeal space, danger space, or pretracheal space into the superior and posterior mediastinum.

- This can lead to necrotizing soft tissue infection of the mediastinum, a surgical emergency.

b. Clinical Features

- Chest pain, dyspnea

- Tachycardia, hypotension

- Rapid progression to sepsis and multi-organ dysfunction

c. Diagnosis

Confirmed by CT scan of the neck and chest showing gas or fluid in the mediastinum

d. Mortality

Mortality rates for DNM range from 25% to 40%, even with surgical drainage and ICU care.

III. Sepsis and Septic Shock

a. Mechanism

- Bacterial translocation into the bloodstream can lead to bacteremia, triggering a systemic inflammatory response.

- Cytokine storm, endothelial dysfunction, and vasodilation follow, potentially leading to septic shock.

b. Complications of Sepsis

- Acute kidney injury

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Multi-organ failure

- High mortality, especially in the elderly or immunocompromised

IV. Necrotizing Fasciitis

a. Definition

Rapidly progressive soft tissue necrosis involving fascia and subcutaneous tissue, often requiring emergency surgery

b. Cause

May develop as a secondary complication of Ludwig’s angina, particularly when anaerobic organisms and gas-forming bacteria are involved

c. Signs

- Skin discoloration (purple, black), crepitus, blistering

- Severe pain out of proportion to exam findings

- Systemic signs of toxicity

V. Internal Jugular Vein Thrombophlebitis (Lemierre’s Syndrome)

a. Mechanism

Spread of infection to the lateral pharyngeal space may involve the internal jugular vein, leading to thrombosis and septic emboli

b. Complications

- Pulmonary emboli and lung abscesses

- Septicemia

c. Organism

Fusobacterium necrophorum is the classic pathogen

VI. Carotid Artery Erosion or Rupture

a. Mechanism

- Infection extending to the carotid sheath may erode the arterial wall

- May result in pseudoaneurysm formation or life-threatening hemorrhage

b. Clinical Warning Signs

- Sudden neck swelling, hematoma

- Profuse bleeding from mouth or wound site

VII. Aspiration Pneumonia

a. Cause

Saliva and infected secretions can be aspirated due to:

Loss of airway control

Altered mental status

Emergency intubation attempts

b. Complications

- Secondary lung infection

- Potential development of abscesses or empyema

VIII. Cranial Nerve Deficits

a. Involvement

Infections involving the base of the skull or lateral neck spaces may impinge on:

Hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) → tongue deviation or paralysis

Glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX) → impaired gag reflex, dysphagia

Vagus nerve (CN X) → hoarseness, vocal cord paralysis

b. Prognosis

May lead to long-term speech or swallowing deficits

IX. Persistent Trismus and Jaw Dysfunction

a. Cause

- Myofascial inflammation, surgical trauma, fibrosis

- Involvement of the masseter or pterygoid muscles

b. Consequences

- Difficulty eating, speaking

- Requires physical therapy or surgical correction

X. Wound and Surgical Complications

- Dehiscence of surgical incision sites

- Infection of surgical drains

- Scar formation and contractures in the submandibular region

- Delayed wound healing, especially in diabetics

XI. Dental and Maxillofacial Sequelae

a. Tooth Loss

Resulting from extraction or necrosis

b. Osteomyelitis of the Mandible

Chronic infection of the jaw bone, potentially requiring prolonged antibiotics or surgical debridement

XII. Psychological and Quality of Life Issues

- Post-traumatic stress from ICU admission or emergency airway intervention

- Disfigurement or visible scarring

- Long recovery time, especially after extensive surgery or tracheostomy

Risk Factors for Developing Complications

| Risk Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Delayed presentation | More time for infection to spread before treatment |

| Diabetes mellitus | Impaired immune response, poor wound healing |

| Immunocompromised status | HIV, chemotherapy, steroids lead to increased vulnerability |

| Inadequate airway control | Increases risk of hypoxia, aspiration, cardiac arrest |

| Poor initial antibiotic therapy | Inadequate microbial coverage may permit unchecked progression |

| Lack of surgical drainage | Persistent infection and abscess formation |

Summary of Ludwig’s Angina Complications

| Category | Key Complications |

|---|---|

| Local | Airway obstruction, abscess formation, trismus, necrotizing fasciitis |

| Regional | Mediastinitis, cranial nerve palsies, vascular erosion |

| Systemic | Sepsis, septic shock, multi-organ failure, aspiration pneumonia |

| Long-term | Facial disfigurement, speech/swallowing difficulty, PTSD, jaw dysfunction |

Prognosis

The prognosis of Ludwig’s angina has improved significantly with prompt diagnosis, airway management, effective antibiotic therapy, and surgical intervention. However, mortality remains a concern, especially in:

- Elderly patients

- Immunocompromised individuals (e.g., diabetics, cancer patients)

- Cases with delayed presentation or treatment

- Patients with descending mediastinitis

Mortality rates have decreased from historical levels of over 50% to less than 10% in most modern series. Early intervention is key.

Prevention

- Prompt treatment of dental infections

- Good oral hygiene

- Dental education and access to dental care

- Avoidance of high-risk behaviors (e.g., unsterile oral piercings)

In high-risk individuals, early referral to dental or medical professionals can prevent complications.

Ludwig’s Angina in Special Populations

Pediatric Patients

Although rare, Ludwig’s angina can occur in children, often due to tonsillitis or submandibular infections. Airway compromise may be more rapid due to smaller anatomical structures.

Diabetic and Immunocompromised Patients

These populations are at higher risk for rapid progression and complications. Blood sugar control and more aggressive management may be necessary.