Root canal treatment (RCT) is a crucial dental procedure that saves millions of teeth annually from extraction by addressing pulp infection. However, like all complex medical interventions, RCT is not without its challenges. One of the most significant complications that can arise during this procedure is the breaking of instruments within the root canal. This complication can turn a routine endodontic treatment into a complex scenario requiring advanced skills and techniques. This article delves into the causes, management strategies, and implications of broken instruments in root canal therapy, providing a comprehensive guide for dental professionals and shedding light on the significance of addressing this issue effectively.

Table of Contents

ToggleUnderstanding Root Canal Treatment

To comprehend the gravity of a broken instrument in a root canal, it is essential first to understand the procedure itself. Root canal treatment involves the removal of infected or damaged pulp from within a tooth, followed by cleaning, shaping, and sealing of the root canal system to prevent reinfection. The procedure typically requires the use of specialized instruments, such as files, which are inserted into the canal to remove debris and shape the space for filling.

The Role of Endodontic Instruments

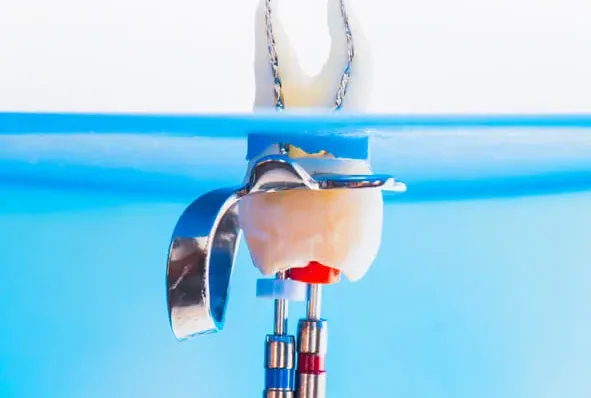

Endodontic instruments, particularly files, play a critical role in root canal therapy. These tools come in various shapes, sizes, and materials, each designed to perform specific functions during the treatment process. The primary types of files used in RCT include stainless steel and nickel-titanium (NiTi) files. These files are responsible for navigating the complex anatomy of the root canal system, removing infected tissue, and shaping the canal to accommodate filling materials.

NiTi files are preferred for their flexibility and ability to navigate curved canals, which are common in molar teeth. However, their flexibility comes with a trade-off: NiTi files are more prone to breakage compared to stainless steel files. Understanding the types and roles of these instruments is crucial in appreciating the challenges posed by their potential breakage during treatment.

Causes of Instrument Breakage in Root Canal Treatment

The breakage of instruments during RCT is a multifactorial problem influenced by a combination of mechanical, procedural, and anatomical factors. Here are some of the most common causes:

- Material Fatigue

- Instrument Design and Manufacturing Defects

- Operator-Related Factors

- Anatomical Complexities

- Inadequate Instrument Sterilization and Maintenance

Material Fatigue

- Nickel-Titanium Files: NiTi files, though highly flexible and efficient in navigating curved canals, are prone to cyclic fatigue. Repeated bending and unbending as the file moves through the canal cause the material to weaken over time, leading to breakage. The risk increases with the complexity of the canal anatomy and the number of uses of the file.

- Stainless Steel Files: While more robust than NiTi files, stainless steel files can also break due to torsional stress, particularly if they become locked in a canal and are subjected to excessive rotational force.

Instrument Design and Manufacturing Defects

Files with smaller diameters, greater taper, or certain flute designs can be more susceptible to breakage. Manufacturing defects, although rare, can also contribute to the sudden fracture of an instrument during use.

Operator-Related Factors

- Technique: Improper use of instruments, such as applying excessive force, using a file beyond its intended lifespan, or failing to recognize the limits of the instrument, can lead to breakage. Additionally, inadequate irrigation and lubrication during the procedure increase friction and stress on the instrument.

- Experience: The operator’s experience plays a significant role in the incidence of instrument breakage. Less experienced practitioners may not be as adept at recognizing early signs of instrument stress or navigating complex canal anatomy, increasing the risk of breakage.

Anatomical Complexities

The complexity of the root canal system, including sharp curvatures, bifurcations, and narrow canals, can contribute to instrument breakage. Files may become wedged in these tight spaces, leading to increased torsional stress and eventual fracture.

Inadequate Instrument Sterilization and Maintenance

Failure to properly clean, sterilize, and inspect instruments between uses can lead to the accumulation of debris and micro-cracks, which weaken the file structure over time. This neglect can significantly increase the risk of breakage during subsequent procedures.

Clinical Implications of Instrument Breakage

The occurrence of a broken instrument in a root canal can have several clinical implications, ranging from mild inconvenience to severe complications that jeopardize the success of the treatment. The significance of these implications depends largely on the location of the fracture, the type of instrument, and the remaining anatomy of the root canal system.

- Impact on Treatment Success

- Prognosis of the Affected Tooth

- Patient Anxiety and Satisfaction

- Legal and Ethical Considerations

Impact on Treatment Success

A broken instrument can obstruct the canal, making it difficult or impossible to fully clean and shape the root canal system. This obstruction can lead to incomplete debridement, leaving behind infected tissue that may cause persistent infection or reinfection.

In some cases, the broken fragment may be located in a non-critical part of the canal system and may not significantly impact the treatment outcome if the remaining canal space can be adequately cleaned and sealed.

Prognosis of the Affected Tooth

The prognosis of a tooth with a retained broken instrument depends on several factors, including the length of the fractured fragment, its location within the canal, and the ability to bypass or remove the fragment. In some cases, the tooth can be successfully treated despite the presence of a broken instrument, but in others, the prognosis may be compromised, leading to potential extraction.

Patient Anxiety and Satisfaction

The discovery of a broken instrument during RCT can increase patient anxiety and dissatisfaction with the treatment. Effective communication and management are essential to reassure the patient and explain the steps that will be taken to address the complication.

Legal and Ethical Considerations

The occurrence of a broken instrument can also have legal and ethical implications. If the complication arises due to operator error or negligence, the practitioner may face legal challenges. Transparent communication with the patient and adherence to best practices are crucial in mitigating these risks.

Management of Broken Instruments in Root Canal Treatment

The management of a broken instrument within the root canal is a critical aspect of endodontic practice. The approach taken depends on various factors, including the location of the fragment, the type of instrument, the stage of the treatment at which the breakage occurred, and the available resources. Management strategies can be broadly categorized into attempts at removal, bypassing the fragment, and leaving the fragment in situ with appropriate precautions.

- Removal of the Broken Instrument

- Bypassing the Fragment

- Leaving the Fragment In Situ

Removal of the Broken Instrument

- Microsurgical Techniques: The use of dental operating microscopes has revolutionized the management of broken instruments. Enhanced magnification and illumination allow for better visualization of the canal and the broken fragment, increasing the chances of successful removal. Ultrasonic tips can be used to create a staging platform around the fragment, facilitating its removal.

- Instrument Retrieval Systems: Specialized retrieval systems, such as the Masserann kit or the Cancellier retrieval system, are designed to grasp and remove broken fragments from the canal. These systems are particularly useful when the fragment is located in the coronal or middle third of the canal.

- Laser Techniques: In some advanced practices, lasers are used to remove the surrounding dentin and free the broken fragment. This technique requires specialized equipment and training but can be effective in certain cases.

Bypassing the Fragment

In situations where removal is not feasible or poses a high risk of further complications, the clinician may attempt to bypass the broken instrument. This involves using smaller, more flexible files to negotiate around the fragment and continue cleaning and shaping the canal. If successful, this approach allows the treatment to proceed with minimal disruption.

Bypassing requires a high level of skill and patience, as there is a risk of creating a ledge, perforation, or transporting the canal, which can further complicate the procedure.

Leaving the Fragment In Situ

In some cases, particularly when the broken fragment is located in the apical third of the canal and the remaining canal space has been adequately cleaned and shaped, the decision may be made to leave the fragment in situ. This approach is often chosen when the risks of removal outweigh the potential benefits, such as in cases where attempting removal could lead to perforation or excessive loss of tooth structure.

When leaving the fragment in place, it is crucial to ensure that the remaining canal system is thoroughly cleaned and sealed to minimize the risk of future infection. The patient should be informed of the situation, and regular follow-up is recommended to monitor the treated tooth.

Preventive Strategies

Preventing instrument breakage is a critical aspect of successful endodontic practice. While it may not be possible to eliminate the risk entirely, several strategies can significantly reduce the likelihood of this complication.

- Proper Instrument Selection and Use

- Avoiding Repeated Use of Instruments

- Adequate Irrigation and Lubrication

- Mastering the Correct Technique

- Regular Maintenance and Sterilization

- Use of Advanced Technology

Proper Instrument Selection and Use

Selecting the appropriate file size, taper, and type for the specific case is essential. Understanding the limitations of each instrument and using it within its intended parameters can prevent undue stress and reduce the risk of breakage.

Avoiding Repeated Use of Instruments

Repeated use of NiTi files increases the risk of material fatigue and breakage. It is recommended to limit the number of uses of each file and to inspect instruments carefully for signs of wear or damage before each use.

Adequate Irrigation and Lubrication

Proper irrigation and lubrication during the procedure reduce friction and torsional stress on the instruments. Using solutions like sodium hypochlorite and EDTA helps to keep the canal clean and reduce debris, which can contribute to instrument binding and breakage.

Mastering the Correct Technique

Practitioners should be well-trained in the correct techniques for using endodontic instruments, including

proper filing motions, speed, and pressure. Understanding canal anatomy and being able to recognize complex or unusual cases are also critical skills that can help prevent instrument breakage. Additionally, clinicians should be cautious when working in highly curved or narrow canals, as these areas are particularly prone to causing instrument fatigue.

Regular Maintenance and Sterilization

Ensuring that instruments are properly cleaned and sterilized between uses is essential for maintaining their integrity. Accumulation of debris, corrosion, or micro-cracks from improper maintenance can significantly increase the risk of instrument failure. Using single-use instruments or limiting the number of sterilization cycles can also help reduce the risk.

Use of Advanced Technology

The adoption of advanced technologies, such as rotary endodontic systems, electronic apex locators, and dental operating microscopes, can improve the precision of root canal procedures and reduce the likelihood of instrument breakage. These tools allow for better visualization and control, enabling practitioners to perform procedures more safely and effectively.

Patient Communication and Ethical Considerations

When a broken instrument occurs during root canal treatment, effective communication with the patient is essential. This involves explaining the situation clearly, discussing the potential implications, and outlining the proposed management strategy. It is important to maintain transparency and honesty to build trust and ensure that the patient is fully informed about their treatment.

- Informed Consent

- Managing Patient Expectations

- Documentation and Legal Aspects

Informed Consent

Before beginning root canal treatment, patients should be informed of the potential risks, including the possibility of instrument breakage. This discussion should be part of the informed consent process, allowing patients to make an educated decision about their treatment.

Providing detailed information about the steps involved in RCT, the tools used, and the potential complications can help patients feel more prepared and less anxious.

Managing Patient Expectations

When a complication such as instrument breakage occurs, it is important to manage patient expectations by explaining the impact of the complication on the treatment outcome. If the fragment can be successfully removed or bypassed, the prognosis is usually favorable.

However, if the fragment must be left in place, the patient should be made aware of the potential need for follow-up care and the possibility of future complications.

Documentation and Legal Aspects

Thorough documentation of the treatment process, including the occurrence of any complications and the steps taken to address them, is essential for legal protection. Detailed records can help defend against potential claims of malpractice and provide evidence that the practitioner acted in accordance with accepted standards of care.

In some cases, it may be advisable to refer the patient to a specialist, such as an endodontist, particularly if the general dentist feels that the complexity of the case exceeds their expertise. This referral should also be documented, along with the specialist’s findings and recommendations.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

The prognosis of a tooth with a broken instrument depends on various factors, including the location of the fragment, the degree of infection or damage to the tooth, and the success of the subsequent management strategies. In many cases, teeth with broken instruments can be successfully treated and retained for many years, provided that the remaining canal system is adequately cleaned, shaped, and sealed.

Factors Influencing Prognosis

- Location of the Fragment

- Stage of Treatment

- Ability to Bypass or Remove the Fragment

- Restorative Follow-Up

Location of the Fragment

Fragments located in the apical third of the canal, especially in multi-rooted teeth, may be less likely to impact treatment success compared to fragments in the coronal or middle third. This is because the apical region may already have been adequately debrided before the instrument broke, reducing the likelihood of residual infection.

Stage of Treatment

If the instrument breaks early in the procedure, before significant cleaning and shaping have been achieved, the prognosis may be poorer due to the potential for retained infection. Conversely, if the breakage occurs late in the procedure, after most of the canal has been cleaned, the impact may be less severe.

Ability to Bypass or Remove the Fragment

Successful removal or bypassing of the fragment greatly improves the prognosis, as it allows the treatment to proceed as planned. When removal is not possible, and the fragment must be left in place, the prognosis depends on the extent of the remaining untreated canal space and the presence of any residual infection.

Restorative Follow-Up

The long-term success of a tooth with a broken instrument also depends on the quality of the restorative work done after RCT. A well-sealed crown or filling can help prevent reinfection and improve the overall prognosis.

Long-Term Monitoring

Teeth with retained broken instruments should be regularly monitored through clinical exams and radiographs to assess the health of the surrounding tissues and detect any signs of failure, such as periapical radiolucency or symptoms of pain and swelling. Early detection of problems can allow for timely intervention, potentially saving the tooth.

Potential for Retreatment or Extraction

In some cases, retreatment may be necessary if the tooth exhibits signs of persistent infection or if new symptoms develop. Retreatment may involve attempts to remove or bypass the broken instrument, or in some cases, surgical procedures such as apicoectomy.

If retreatment is not successful or if the prognosis is poor, extraction may be the final option. While extraction is a last resort, it is sometimes the best course of action to prevent further complications and to allow for subsequent restorative options, such as dental implants or bridges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What happens if a tool breaks during a root canal?

If a tool breaks during a root canal, the approach to managing it depends on its location and impact on the treatment. If the fragment is in an area where it does not hinder the cleaning and sealing of the canal, it may be left in place without causing problems. However, if the broken piece obstructs proper treatment, removal or bypassing the fragment may be necessary. In some cases, a specialist endodontist may be required to perform advanced techniques to retrieve the tool.

How do they remove broken instruments from a root canal?

Endodontists use specialized tools and techniques to remove broken instruments from a root canal. Ultrasonic instruments can be used to vibrate and loosen the fragment, while fine tweezers or micro-endodontic techniques help extract the broken piece carefully. In some cases, a small portion of the tooth structure may need to be removed to access and retrieve the instrument. If removal is not possible without causing additional damage, the canal may be sealed around the fragment to ensure a successful outcome.

What are the complications of a broken file in a root canal?

A broken file in a root canal can lead to various complications, including incomplete removal of infected pulp tissue, which increases the risk of reinfection. The presence of a broken instrument may also prevent full cleaning and shaping of the canal, leading to persistent pain or failure of the root canal treatment. In some cases, the tooth may require retreatment or even extraction if the infection persists or spreads to surrounding tissues.

How common is a broken file in a root canal?

Instrument separation during a root canal is relatively rare but can occur, especially in cases where the canals are highly curved or calcified. The risk is higher when treating complex root structures or when using older, more brittle instruments. However, advancements in endodontic tools and techniques, as well as careful procedural techniques by skilled practitioners, have significantly reduced the frequency of broken files.

Is it okay to leave a broken file in the root canal?

In some situations, a broken file may be left in the root canal if it is located in an area that has already been thoroughly disinfected and does not interfere with the sealing process. If the fragment is deeply embedded and poses no risk of infection, it may not cause any issues. However, if the broken file is in a critical location and prevents proper cleaning or sealing, it should be removed or bypassed to ensure long-term treatment success.

What happens if you mess up a root canal?

If a root canal is not performed correctly, it can lead to ongoing pain, infection, and even tooth loss. A failed root canal may occur due to incomplete removal of infected pulp, improper sealing of the canals, or reinfection caused by leakage. If a root canal fails, it may require retreatment by an endodontist, where the procedure is redone with improved techniques. In severe cases, the tooth may need to be extracted and replaced with a dental implant or bridge.

What are the complications of instrument separation?

When an instrument separates within a root canal, several complications can arise. The most common issue is the inability to completely clean and disinfect the canal, increasing the risk of infection or reinfection. A broken instrument may also obstruct the filling material, leading to an improper seal. In some cases, an unresolved broken instrument may contribute to long-term pain or the eventual need for surgical intervention, such as an apicoectomy, or even extraction.

Who removes a failed root canal?

A failed root canal is typically handled by an endodontist, a specialist in root canal treatments. They use advanced tools such as microscopes and ultrasonic instruments to retreat the tooth by removing old filling material, disinfecting the canal, and resealing it properly. If retreatment is not possible, a surgical procedure such as an apicoectomy may be performed to remove the infection. In cases where the tooth cannot be saved, an oral surgeon or dentist may extract it and recommend a suitable replacement option, such as a dental implant or bridge.