Tetanus, often referred to as “lockjaw,” is a serious bacterial infection caused by Clostridium tetani. This condition is characterized by muscle stiffness and spasms, which can lead to severe complications or even death if not treated promptly. While tetanus is commonly associated with injuries involving puncture wounds or contaminated objects, its relevance extends into various medical fields, including dentistry. In dental practice, understanding the nature of tetanus, its risks, and prevention strategies is crucial to ensuring patient safety and maintaining high standards of care.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Pathophysiology of Tetanus

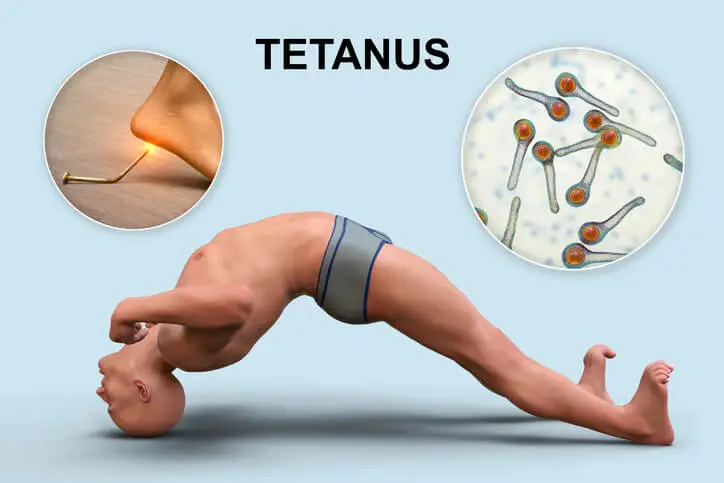

Clostridium tetani is an anaerobic, spore-forming bacterium found in soil, dust, and animal feces. When introduced into the body through a wound, the spores can germinate in an anaerobic environment, leading to the production of tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin. This toxin interferes with normal muscular control by blocking inhibitory neurotransmitter release, resulting in unopposed muscle contractions and spasms.

The incubation period for tetanus ranges from a few days to several weeks, depending on the wound’s proximity to the central nervous system and the amount of toxin produced. Early symptoms include muscle stiffness in the jaw and neck, progressing to more severe manifestations such as generalized muscle spasms, respiratory difficulty, and autonomic dysfunction.

Tetanus in Dentistry

While tetanus is often associated with traumatic injuries, its relevance in dentistry should not be underestimated. Dental procedures inherently involve the manipulation of tissues, use of sharp instruments, and potential for exposure to pathogens. Moreover, patients with oral infections or compromised immune systems are particularly vulnerable. Therefore, dental practitioners must be vigilant in recognizing potential tetanus risks and implementing appropriate preventative measures.

Wound Management and Tetanus Risk

Dental procedures, especially extractions and surgeries, can create open wounds in the oral cavity. These sites can become entry points for Clostridium tetani if contaminated with spores. The risk is heightened in patients with poor oral hygiene, untreated dental caries, or pre-existing oral infections, as these conditions can provide an anaerobic environment conducive to bacterial growth.

Patient History and Vaccination Status

A thorough patient history, including tetanus vaccination status, is essential in dental practice. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that adults receive a tetanus booster every ten years. Dental practitioners should inquire about the patient’s last tetanus shot, especially before invasive procedures. If there is any doubt or the patient has not been vaccinated within the last decade, a booster may be recommended.

Aseptic Techniques and Infection Control

Strict adherence to aseptic techniques and infection control protocols is vital to prevent tetanus and other infections in dental settings. This includes the sterilization of instruments, use of disposable items when possible, and proper handling of sharps. Dental practitioners should also ensure that all wounds are thoroughly cleaned and debrided to minimize the risk of infection.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Recognizing the clinical presentation of tetanus is crucial for timely intervention. Initial symptoms often include trismus (lockjaw), difficulty swallowing, and muscle rigidity in the neck and face. As the disease progresses, generalized muscle spasms may occur, which can be severe and painful. These spasms can be triggered by minor stimuli such as a light touch, noise, or even a draft.

Diagnosis of tetanus is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic symptoms and patient history. Laboratory tests may support the diagnosis but are not definitive. In a dental context, practitioners should maintain a high index of suspicion if a patient presents with compatible symptoms following a recent dental procedure, especially if their vaccination status is uncertain.

Management and Treatment

The management of tetanus involves both supportive care and specific treatments to neutralize the toxin and control muscle spasms. Key components of tetanus management include:

- Wound Care

- Antitoxin Administration

- Antibiotic Therapy

- Muscle Spasm Control

- Vaccination

Wound Care

Thorough cleaning and debridement of the wound are critical to removing the source of Clostridium tetani. This may involve surgical intervention to excise necrotic tissue and create an aerobic environment that is less conducive to bacterial growth.

Antitoxin Administration

Human tetanus immune globulin (TIG) is administered to neutralize the circulating toxin. The dose and route of administration depend on the severity of the infection and the patient’s immune status.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics, such as metronidazole or penicillin, are used to eradicate the bacteria and prevent further toxin production. These medications are typically administered intravenously.

Muscle Spasm Control

Muscle spasms are managed with medications such as benzodiazepines or neuromuscular blocking agents. In severe cases, mechanical ventilation may be necessary to support respiration.

Vaccination

In addition to immediate treatment, patients should receive a tetanus vaccination to boost their immunity and prevent future infections. This is especially important for patients who were not up to date with their tetanus immunizations prior to the infection.

Prevention in Dental Practice

Preventing tetanus in dental settings involves a multifaceted approach that includes vaccination, infection control, patient education, and adherence to best practices in wound management.

- Vaccination

- Infection Control

- Patient Education

- Wound Management

Vaccination

Ensuring that patients are up to date with their tetanus vaccinations is a cornerstone of prevention. Dental practitioners should review vaccination records and recommend boosters as needed, especially for patients undergoing invasive procedures.

Infection Control

Strict adherence to infection control protocols is essential. This includes the use of sterilized instruments, disposable items when appropriate, and proper hand hygiene. Dental staff should be trained in aseptic techniques and the proper handling of sharps to prevent injuries.

Patient Education

Educating patients about the importance of good oral hygiene and regular dental visits can help prevent oral infections that may create a suitable environment for Clostridium tetani. Patients should also be informed about the signs and symptoms of tetanus and the importance of timely vaccination.

Wound Management

Proper wound care is crucial in preventing tetanus. This involves thorough cleaning and debridement of wounds, use of appropriate antiseptics, and careful monitoring of the healing process. Dental practitioners should be vigilant in identifying wounds at risk for infection and taking appropriate steps to mitigate those risks.

Conclusion

Tetanus remains a significant public health concern despite the availability of effective vaccines. In the field of dentistry, understanding the risks associated with tetanus and implementing appropriate preventive measures is crucial to ensuring patient safety. By maintaining high standards of infection control, staying vigilant about patient vaccination status, and providing thorough wound care, dental practitioners can significantly reduce the risk of tetanus in their patients. As part of a comprehensive approach to patient care, these practices contribute to the overall health and well-being of individuals receiving dental treatment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How do you tell if a cut will give you tetanus?

You can’t determine with certainty just by looking at a wound whether it will lead to tetanus. However, some types of wounds are more likely to be risky. These include deep puncture wounds (like from nails, splinters, or animal bites), especially if they are contaminated with dirt, dust, manure, or saliva. Tetanus bacteria (Clostridium tetani) thrive in low-oxygen environments, such as deep or narrow wounds where air doesn’t circulate well. Burns, crush injuries, and dead tissue also increase the risk. If you’re unsure, it’s best to consult a healthcare provider, especially if you’re not up to date on your tetanus vaccinations.

What are the symptoms of tetanus infection?

Tetanus symptoms often begin gradually and can take days or weeks to appear after the injury. Early signs include:

- Jaw stiffness (commonly known as “lockjaw”)

- Muscle spasms or stiffness, especially in the neck, shoulders, or back

- Difficulty swallowing or speaking

- Irritability or restlessness

- Headache or fever

- Sweating and elevated blood pressure

As the infection progresses, muscle spasms can become severe and painful, sometimes affecting breathing and causing life-threatening complications. Immediate medical attention is critical.

Can you heal from tetanus?

Yes, it is possible to recover from tetanus with prompt and appropriate treatment. Treatment typically includes:

- Tetanus immune globulin (TIG) to neutralize the toxin

- Antibiotics to kill the bacteria

- Wound care to remove dead tissue

- Muscle relaxants or sedatives to control spasms

- Supportive care, which may include mechanical ventilation in severe cases

Recovery can take weeks or even months, especially in severe cases. Survivors often need physical therapy to regain full muscle function. However, without treatment, tetanus can be fatal, especially in older adults or unvaccinated individuals.

How fast does tetanus set in?

The incubation period—the time between injury and the appearance of symptoms—typically ranges from 3 to 21 days, with an average of about 8 days. The closer the wound is to the central nervous system, the shorter the incubation period tends to be. A shorter incubation time usually means a more severe case. That’s why timely medical evaluation and vaccination are essential after a high-risk injury.

What are the odds of getting tetanus from a cut?

The actual risk depends on a few factors: your vaccination status, the type and cleanliness of the wound, and whether the wound was properly treated. Tetanus is rare in countries with widespread vaccination, like the U.S., but it can still happen—especially if someone hasn’t had a booster shot in over 10 years. In developing countries or among unvaccinated individuals, the risk is significantly higher. While the odds of developing tetanus from a minor cut are low for someone fully vaccinated, it’s still important to take precautions.

How long after a cut do you have to get a tetanus shot?

The ideal window to receive a tetanus shot after a potentially risky injury is within 24 to 72 hours. If your last booster was over 10 years ago—or 5 years ago for a very dirty wound—you should get a booster as soon as possible. Getting the vaccine quickly can prevent the infection from developing, especially if the bacteria haven’t yet produced a significant amount of toxin.

How soon will I know if I have tetanus?

Symptoms can appear anywhere from 3 to 21 days after the injury. Early symptoms often include:

- Stiffness in the jaw (lockjaw)

- Neck tightness

- Difficulty opening the mouth or swallowing

If you experience any of these symptoms after a wound—especially one involving a dirty or rusty object—seek immediate medical attention. The longer you wait, the more serious the condition can become.

Do I need a tetanus shot for a small puncture?

Yes, even small punctures can lead to tetanus, particularly if the object was contaminated with soil, dust, or rust. The bacteria don’t need a big opening to enter your body. If it’s been more than 10 years since your last booster (or more than 5 years for dirty wounds), you should get a tetanus shot. It’s always better to be cautious with any skin-breaking injury.

Can I get a tetanus shot at a pharmacy?

Yes, many pharmacies—especially larger chains like CVS, Walgreens, and Rite Aid—offer tetanus shots, often as part of a Td (Tetanus and Diphtheria) or Tdap (Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Pertussis) vaccine. No prescription is usually needed, but availability may vary by location and age group, so it’s a good idea to call ahead.

How deep does a wound need to be for tetanus?

There is no specific depth that guarantees tetanus risk, but deeper wounds are more likely to create the anaerobic (low oxygen) conditions where tetanus bacteria thrive. That said, shallow wounds can still become infected, especially if they are dirty or not cleaned properly. It’s not about depth alone—contamination and your vaccination status matter more.

Can I get a tetanus shot 4 days after injury?

Yes, you can and should still get a tetanus shot 4 days after a potentially risky injury. The vaccine is most effective when given within a few days of the injury and can still help your body prevent the bacteria from producing dangerous toxins. It’s important not to delay, though—getting the shot sooner is better.

What happens if you step on a rusty nail and don’t get a tetanus shot?

If you’re not protected by vaccination and you step on a rusty or dirty nail, you are at risk of developing tetanus. The nail itself doesn’t have to be rusty—what matters is the presence of the bacteria on the nail or in the wound. Without treatment, tetanus can lead to severe muscle spasms, breathing difficulties, and death. Immediate wound cleaning and a tetanus shot are essential to reduce the risk.