Dental implants have become a cornerstone of modern restorative dentistry, offering predictable, long-term solutions for the replacement of missing teeth. Advances in biomaterials, surgical techniques, imaging, and digital planning have significantly improved implant success rates and patient satisfaction. However, despite these advancements, successful implant therapy is not merely dependent on surgical skill or implant design. Instead, it relies heavily on meticulous planning, comprehensive patient assessment, and careful consideration of anatomical, biological, prosthetic, and patient-related factors.

Implant planning is a multidisciplinary process that integrates restorative dentistry, periodontology, oral surgery, prosthodontics, and radiology. A systematic approach ensures optimal implant positioning, long-term osseointegration, functional stability, and aesthetic outcomes.

Table of Contents

ToggleAssessment of Suitability for Implant Placement

Comprehensive Patient History

The foundation of implant planning begins with a thorough medical and dental history. Systemic health conditions may influence wound healing, osseointegration, and the risk of postoperative complications. Conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, immunosuppression, and renal disease should be carefully evaluated. The clinician must also identify current medications, particularly those associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ), such as bisphosphonates and denosumab.

A detailed dental history should assess previous periodontal disease, caries risk, oral hygiene habits, and past restorative treatments. Patients with a history of periodontitis are at increased risk of peri-implant diseases and implant failure, making long-term maintenance planning essential.

Clinical Examination

Hard and Soft Tissue Assessment

Clinical examination should include evaluation of both hard and soft tissues. The quantity and quality of keratinized mucosa are important for maintaining peri-implant health. Thin soft tissue biotypes are associated with higher recession risk and may compromise aesthetic outcomes, especially in the anterior region.

Bone availability must be assessed in terms of volume, density, and morphology. Adequate alveolar bone height and width are necessary to accommodate the implant fixture while maintaining safe distances from adjacent anatomical structures.

Occlusion and Interarch Space

Occlusal analysis is a critical component of implant planning. The clinician must assess:

- Existing occlusal scheme

- Parafunctional habits such as bruxism

- Available interocclusal space

Insufficient vertical space may compromise prosthetic design, while excessive occlusal forces can increase the risk of implant overload and mechanical failure. Interdental space must also be sufficient to allow proper implant placement and emergence profile.

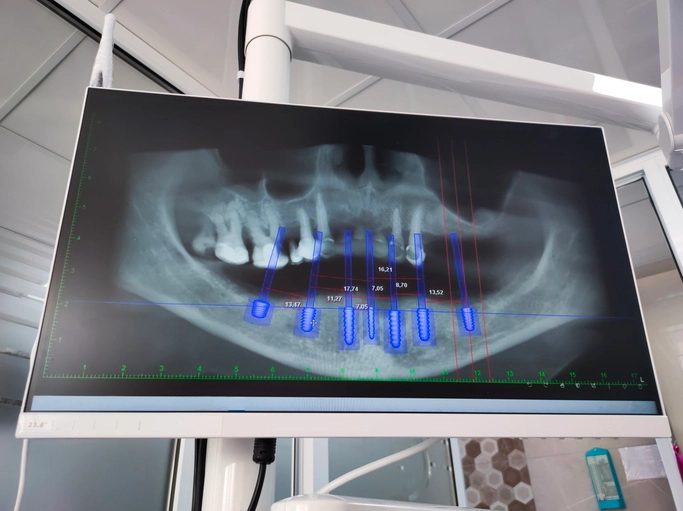

Radiographic Examination

Radiographic assessment complements clinical findings and is essential for evaluating bone dimensions and anatomical landmarks. Traditional plain film radiographs, such as periapical and panoramic images, can provide information about bone height and proximity to vital structures such as:

- Inferior dental canal

- Maxillary sinus

- Adjacent tooth roots

However, two-dimensional imaging has limitations, including magnification errors and lack of buccolingual assessment. Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) has become the gold standard for implant planning, offering three-dimensional visualization of bone volume, density, and anatomical structures. Despite its advantages, CBCT involves increased radiation exposure, emphasizing the importance of justification and use of limited field-of-view scans where appropriate.

Consideration of Prosthetic Options

Implant therapy should never be considered in isolation. Alternative prosthetic options must be discussed, including:

- No treatment

- Removable partial dentures

- Fixed dental prostheses (bridges)

Patients must be informed of the benefits, limitations, costs, and maintenance requirements of each option. Informed consent requires that implant treatment is presented as one of several viable choices rather than the default solution.

Indications for Dental Implants

Dental implants are indicated in a wide range of clinical scenarios, including:

Edentulous and Partially Edentulous Patients

Implants can significantly improve denture retention, stability, and function in fully edentulous patients. Implant-supported overdentures reduce alveolar bone resorption and enhance quality of life. In partially edentulous patients, implants prevent the need to prepare adjacent teeth for fixed bridges.

Multiple Missing Teeth

Implants can support fixed or removable prostheses in patients with multiple missing teeth, restoring function and aesthetics while preserving remaining tooth structure.

Single Tooth Replacement

Single tooth implants are a conservative alternative to fixed bridges, provided sufficient space is available. A minimum interdental space of approximately 6.5–7 mm is required to accommodate a standard implant fixture and restoration while maintaining appropriate distances from adjacent teeth.

Maxillofacial Rehabilitation

Implants play a crucial role in the rehabilitation of patients following cancer surgery or trauma. They provide retention and support for complex maxillofacial prostheses, improving speech, mastication, and facial aesthetics.

Relative Contraindications for Implant Placement

While few absolute contraindications exist, several relative contraindications must be carefully considered and managed.

Local Factors

Poor plaque control and untreated periodontal disease significantly increase the risk of peri-implantitis. Adequate oral hygiene and periodontal stability are prerequisites for implant placement.

Bone quality and soft tissue biotype also influence implant success. Poor bone density may compromise primary stability, while thin soft tissues increase the risk of recession and aesthetic failure.

Systemic Factors

Smoking is a well-documented risk factor for impaired healing, increased implant failure, and peri-implant disease. Patients should be encouraged to cease smoking prior to and following implant surgery.

Systemic conditions such as poorly controlled diabetes, immunosuppression, chronic kidney disease, and ongoing chemotherapy can impair healing and increase infection risk. Radiotherapy to the jaws poses additional challenges due to compromised vascularity and bone vitality.

Medication-Related Risks

Patients receiving bisphosphonates or denosumab, particularly intravenously, are at increased risk of MRONJ. Risk assessment must consider the type, dose, and duration of therapy, and implant placement should be approached with caution.

Psychosocial Factors

Unrealistic patient expectations and unfavourable smile lines can compromise satisfaction with implant outcomes. Comprehensive patient education and expectation management are essential components of treatment planning.

Planning of Implant Position

Prosthetically Driven Planning

Modern implant planning follows a “top-down” or prosthetically driven approach. Rather than placing the implant based solely on available bone, the final restoration determines implant position. This approach ensures optimal aesthetics, function, and long-term maintenance.

Diagnostic Wax-Ups and Digital Planning

Diagnostic wax-ups on mounted study models allow visualization of the final tooth position. These wax-ups can be transferred into radiographic stents, which guide imaging and surgical planning.

Digital workflows have become increasingly popular, allowing virtual implant placement using CBCT data and digital impressions. Implant planning software enables three-dimensional evaluation and fabrication of surgical guides.

Spatial Requirements

Proper spacing is critical for implant success:

- A minimum of 1.5 mm should be maintained between the implant and adjacent teeth.

- For a 4 mm diameter implant, at least 7 mm of interdental space is required.

- A minimum of 3 mm should be maintained between adjacent implants to preserve interproximal bone and soft tissue health.

When these spatial requirements cannot be met, alternative prosthetic options or bone augmentation procedures must be considered.

Bone Augmentation in Implant Dentistry

Indications for Bone Augmentation

Bone augmentation is required when insufficient bone volume prevents ideal implant placement. Causes of bone deficiency include tooth loss, trauma, periodontal disease, and long-term denture wear.

Bone Augmentation Techniques

Several techniques are available, depending on the clinical scenario:

- Guided Bone Regeneration (GBR): Uses barrier membranes to exclude soft tissue and promote bone regeneration.

- Block Bone Grafting: Autogenous bone blocks are fixed to deficient sites to increase bone volume.

- Ridge Expansion: Increases ridge width in narrow alveolar crests.

- Sinus Elevation: Increases vertical bone height in the posterior maxilla.

- Distraction Osteogenesis: Gradual mechanical separation stimulates new bone formation.

Bone Grafting Materials

Bone graft materials may be classified as:

- Autogenous bone: Harvested from the patient; considered the gold standard due to osteogenic potential.

- Allografts: Human donor bone from tissue banks.

- Xenografts: Animal-derived bone substitutes.

- Alloplastic materials: Synthetic materials such as hydroxyapatite and calcium sulfate.

Each material has advantages and limitations, and selection depends on defect size, patient factors, and clinician preference.

Adjunctive Therapies

Barrier membranes are commonly used to support graft stability and prevent soft tissue ingrowth. Bioactive agents such as bone morphogenetic proteins and platelet concentrates (e.g., PRGF) may enhance healing and accelerate osseointegration.

Timing of Bone Augmentation

Bone augmentation may be performed simultaneously with implant placement if sufficient bone is present to achieve primary stability and allow soft tissue closure. Alternatively, a staged approach may be required, with bone augmentation performed first and implant placement delayed by 3–6 months.

Early implant planning prior to tooth extraction can reduce post-extraction bone resorption and improve outcomes.

Conclusion

Planning for dental implants is a complex, multifactorial process that extends far beyond surgical placement. Comprehensive assessment, prosthetically driven planning, appropriate use of imaging, and careful consideration of biological and patient-related factors are essential for predictable outcomes. Bone augmentation techniques and digital workflows have expanded treatment possibilities, allowing clinicians to manage challenging cases with greater confidence.

Ultimately, successful implant therapy depends on meticulous planning, interdisciplinary collaboration, and patient-centered care. By adhering to sound principles and evidence-based protocols, clinicians can achieve functional, aesthetic, and long-lasting implant restorations.

References

- Esposito M, Hirsch JM, Lekholm U, Thomsen P.

Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants (I). Success criteria and epidemiology.

European Journal of Oral Sciences. 1998;106(1):527–551. - Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, Eriksson AR.

The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: A review and proposed criteria of success.

International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 1986;1(1):11–25. - Buser D, Martin W, Belser UC.

Optimizing esthetics for implant restorations in the anterior maxilla: Anatomical and surgical considerations.

International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2004;19(Suppl):43–61. - Lang NP, Berglundh T; Working Group 4 of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology.

Periimplant diseases: Where are we now?—Consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology.

Journal of Clinical Periodontology. 2011;38(Suppl 11):178–181. - Misch CE.

Dental Implant Prosthetics. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2015. - Misch CE.

Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. - Buser D, Sennerby L, De Bruyn H.

Modern implant dentistry based on osseointegration: 50 years of progress, current trends, and open questions.

Periodontology 2000. 2017;73(1):7–21. - Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Polyzos IP, Felice P, Worthington HV.

Interventions for replacing missing teeth: Dental implants in fresh extraction sockets (immediate, immediate-delayed and delayed implants).

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;CD005968. - Hammerle CHF, Jung RE.

Bone augmentation by means of barrier membranes.

Periodontology 2000. 2003;33:36–53. - Aghaloo TL, Moy PK.

Which hard tissue augmentation techniques are the most successful in furnishing bony support for implant placement?

International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2007;22(Suppl):49–70. - Chen ST, Buser D.

Clinical and esthetic outcomes of implants placed in postextraction sites.

International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2009;24(Suppl):186–217. - Bornstein MM, Scarfe WC, Vaughn VM, Jacobs R.

Cone beam computed tomography in implant dentistry: A systematic review focusing on guidelines, indications, and radiation dose risks.

International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants. 2014;29(Suppl):55–77. - Lang NP, Tonetti MS.

Periodontal risk assessment (PRA) for patients in supportive periodontal therapy (SPT).

Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry. 2003;1(1):7–16. - Mombelli A, Müller N, Cionca N.

The epidemiology of peri-implantitis.

Clinical Oral Implants Research. 2012;23(Suppl 6):67–76. - Sakka S, Coulthard P.

Implant failure: Etiology and complications.

Medicina Oral, Patología Oral y Cirugía Bucal. 2011;16(1):e42–e44.