Periapical lesions are pathological conditions located at or near the apex of a tooth root, typically resulting from infection of the pulp chamber due to caries, trauma, or other irritants. These lesions are the body’s immune response to bacterial invasion that has spread beyond the root canal system into the periapical tissues.

In endodontic pathology, periapical lesions serve as a critical indicator of the progression of pulpal disease and often determine the course of clinical intervention. Though many lesions may appear similar radiographically, they vary histologically and in terms of treatment outcomes.

Table of Contents

TogglePeriapical Lesion Causes

1. Pulpal Necrosis Due to Dental Caries

Dental caries is the most common cause of pulpal and periapical pathologies. When bacteria penetrate the enamel and dentin, they eventually reach the pulp chamber. As the pulp becomes infected and inflamed (pulpitis), it progresses to irreversible pulpitis and ultimately pulpal necrosis if left untreated. The necrotic tissue becomes a reservoir for anaerobic bacteria which then colonize the root canal system. The bacterial toxins and metabolic byproducts escape through the apex, triggering an inflammatory reaction in the periapical tissues.

2. Traumatic Injuries

Trauma, such as fractures or luxation injuries, can directly damage the pulp without the involvement of bacteria initially. In such cases, the pulp becomes necrotic due to disruption of the blood supply. A necrotic pulp provides a favorable environment for microbial growth over time, resulting in a periapical lesion. Traumatized anterior teeth in children and young adults are particularly susceptible due to thinner dentinal walls and open apices.

3. Iatrogenic Factors

Dental procedures themselves can lead to pulp and periapical pathologies if not carefully performed. Common iatrogenic causes include:

- Overheating during tooth preparation: Can damage the pulp leading to necrosis.

- Excessive or repeated restorative procedures: Can traumatize the pulp tissue.

- Pulp exposure during cavity preparation: Can allow microbial contamination.

- Over-instrumentation during endodontic therapy: Can push debris and bacteria beyond the apex, causing inflammation or abscess.

- Perforation of the root or floor: Allows communication between the root canal and periradicular tissues, facilitating bacterial invasion.

- Improper obturation: Incomplete filling of the canal may leave space for bacterial colonization and persistent infection.

4. Cracked Tooth Syndrome

Microfractures in a tooth can serve as a hidden pathway for bacteria to reach the pulp and then the periapical area. This condition is difficult to diagnose and often overlooked. If untreated, these microscopic cracks can result in pulpal necrosis and eventually periapical lesions.

5. Periodontal-Endodontic Lesions

Periodontal disease can occasionally lead to secondary pulpal involvement through lateral canals, apical foramen, or dentinal tubules. Conversely, endodontic infections can exacerbate or mimic periodontal conditions. When communication exists between a deep periodontal pocket and the apex of the tooth, bacteria may travel and cause periapical inflammation.

6. Developmental Anomalies

Certain developmental conditions can predispose teeth to early pulpal necrosis, including:

- Dens invaginatus: Creates an anatomical invagination that may allow bacterial entry close to the pulp.

- Cemento-osseous dysplasia: Though not primarily infectious, may mimic or co-exist with periapical lesions radiographically.

- Incomplete root formation in young permanent teeth can make them more susceptible to bacterial invasion.

7. Systemic Conditions and Immune Factors

Although periapical lesions are local manifestations, systemic factors can influence their development and progression:

- Diabetes mellitus: Impaired immune response and healing may exacerbate inflammation and delay recovery.

- Immunosuppression (e.g., HIV, cancer therapy): Can lead to atypical presentations or more aggressive lesions.

- Genetic predisposition: Certain individuals may mount a more exaggerated immune response leading to more severe periapical lesions.

How Periapical Lesions Develop

The formation of a periapical lesion is a dynamic, multifactorial process involving microbial invasion, host immune response, and inflammatory tissue changes. The following stages outline the typical pathogenesis:

1. Pulpal Necrosis and Microbial Colonization

Once the pulp tissue becomes necrotic, it serves as an ideal medium for microbial proliferation. The environment becomes anaerobic, promoting the growth of obligate anaerobes such as Porphyromonas, Prevotella, and Fusobacterium species.

2. Microbial Products Reach Periapex

Bacteria and their byproducts such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), peptidoglycans, proteolytic enzymes, and exotoxins exit through the apical foramen and initiate an immune response in the periapical tissue.

3. Immune Response and Inflammation

- Acute Phase: Neutrophils are the first responders, leading to pus formation and abscess development.

- Chronic Phase: When the infection is persistent or less aggressive, chronic inflammation ensues. Macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells predominate. Cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α are released, promoting osteoclastic activity and bone resorption.

4. Lesion Maturation

Based on the balance between microbial virulence and host defense mechanisms, different types of lesions may form:

- Periapical granuloma: Granulation tissue formed with chronic inflammatory cells and fibroblasts.

- Periapical cyst: A granuloma may stimulate epithelial proliferation (from epithelial rests of Malassez), forming a cystic cavity.

- Abscess: When neutrophils dominate and tissue liquefaction occurs, an abscess forms with pus and potential for sinus tract formation.

5. Bone Resorption

Osteoclasts, under the influence of pro-inflammatory mediators like RANKL (Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor κB Ligand), resorb alveolar bone around the apex, leading to a radiolucent area visible on radiographs.

6. Healing vs. Persistence

- If the source of infection is eliminated (e.g., via root canal therapy), resolution and bone regeneration typically follow.

- If infection persists or is inadequately treated, the lesion may remain static, grow, or become a chronic draining abscess.

Classification of Periapical Lesions

Periapical lesions are a group of pathological conditions affecting the apex (tip) of a tooth root, typically as a consequence of pulpal necrosis. Accurate classification is essential for effective diagnosis and treatment, especially since different lesions can present with similar clinical and radiographic features.

Periapical lesions are classified based on their histopathological nature into inflammatory, cystic, and suppurative types. The three most common periapical lesions are:

- Periapical (Chronic) Granuloma

- Periapical (Radicular) Cyst

- Periapical Abscess

Less common and less understood lesions or radiographic appearances may also mimic periapical pathology, such as:

- Condensing Osteitis

- Periapical Scar

- Non-Endodontic Lesions (e.g., neoplasms, fibro-osseous lesions)

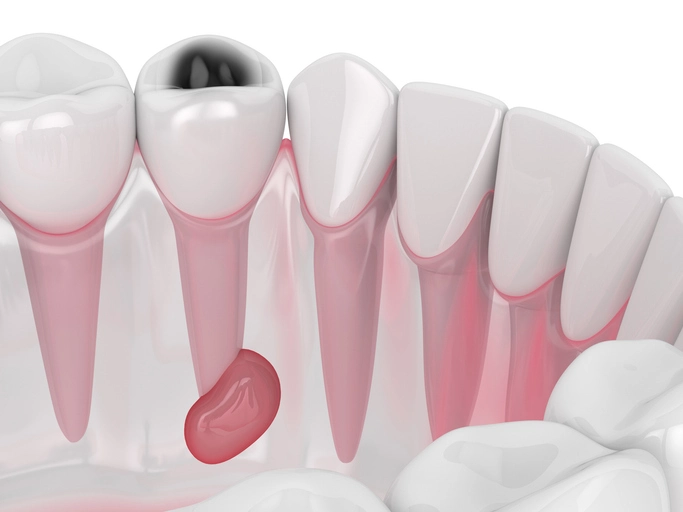

1. Periapical Granuloma

Definition

A periapical granuloma is a localized mass of chronic inflammatory granulation tissue at the apex of a non-vital tooth. It is not a true granuloma in the immunologic sense but rather a chronic inflammatory response.

Pathogenesis

It forms as a chronic immune response to persistent irritants from the necrotic pulp and microbial toxins.

Histology

- Composed of granulation tissue with inflammatory cells: lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages.

- May contain multinucleated giant cells and cholesterol clefts.

- Epithelial rests of Malassez may be present and can give rise to cysts.

Radiographic Features

- Well-defined radiolucency at the root apex.

- May be circular or oval, with or without a radiopaque border.

- Typically less than 1 cm in diameter.

Clinical Relevance

- Usually asymptomatic unless acutely inflamed.

- Responds well to conventional root canal treatment.

- Can be indistinguishable from cysts radiographically without histology.

2. Periapical (Radicular) Cyst

Definition

A periapical cyst, also known as a radicular cyst, is a true cyst (an epithelium lined cavity) arising from the proliferation of epithelial rests of Malassez in response to chronic inflammation.

Types of Periapical Cysts

- Pocket (Bay) Cyst: Connected to the root canal system.

- True Cyst: Completely enclosed and not connected to the root canal.

Pathogenesis

Develops from chronic periapical granulomas where epithelial proliferation leads to cyst formation. Stimuli include inflammatory mediators and cellular debris.

Histology

- Central lumen filled with fluid or necrotic debris.

- Lined by stratified squamous epithelium.

- Surrounded by fibrous connective tissue and chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

Radiographic Features

- Well-circumscribed radiolucency, often larger than granulomas (>1 cm).

- May exhibit a radiopaque margin or corticated border.

- Usually at the apex of a non-vital tooth.

Clinical Relevance

- May remain asymptomatic for long periods.

- True cysts are less likely to heal with root canal therapy alone.

- Large cysts or those resistant to conservative therapy may require surgical enucleation (apicoectomy).

3. Periapical Abscess

Definition

A periapical abscess is an acute or chronic localized accumulation of pus at the apex of a tooth root due to bacterial infection.

Types

- Acute Periapical Abscess: Rapid onset, severe pain, systemic signs (fever, malaise).

- Chronic Periapical Abscess: Slow progression, may drain through a sinus tract, minimal pain.

Pathogenesis

Occurs when the immune system fails to contain the infection, leading to tissue liquefaction and pus formation.

Histology

- Central zone of necrosis and pus with neutrophilic infiltration.

- Surrounding connective tissue infiltrated with chronic inflammatory cells.

Radiographic Features

- May appear as a diffuse radiolucency or show no changes initially.

- Bone destruction around apex is irregular and poorly demarcated in acute cases.

Clinical Relevance

- Presents with pain, swelling, tooth tenderness, and systemic symptoms.

- Requires urgent drainage, antibiotic therapy (in severe cases), and root canal treatment or extraction.

4. Condensing Osteitis (Focal Sclerosing Osteomyelitis)

Definition

A reactive lesion characterized by localized bone sclerosis in response to low-grade chronic inflammation, often from a non-vital tooth.

Radiographic Features

- Radiopaque lesion at the apex of a tooth.

- Usually associated with mandibular molars and premolars.

- No clear radiolucency; bone appears denser and more sclerotic.

Clinical Relevance

- Tooth may be asymptomatic or have a history of trauma or pulpitis.

- Pulp usually necrotic; root canal therapy is indicated.

- No surgical intervention typically required unless lesion persists.

5. Periapical Scar

Definition

A fibrous tissue scar that forms after endodontic surgery or extraction, particularly when both facial and lingual cortical plates have been lost.

Radiographic Features

- Persistent radiolucency despite successful treatment.

- Remains stable over time with no clinical symptoms.

Clinical Relevance

- Important to differentiate from persistent infection.

- Biopsy or periodic monitoring may be warranted to rule out pathology.

6. Other Lesions that Mimic Periapical Pathology

Some radiolucent or radiopaque lesions may appear similar to periapical lesions but are unrelated to pulp pathology:

| Lesion | Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|

| Cemento-osseous dysplasia | Occurs in middle-aged females, vital teeth, mixed radiolucent/opaque. |

| Odontogenic keratocyst | Aggressive, can mimic cysts, may recur. |

| Ameloblastoma | Expansile, multilocular radiolucency, usually posterior mandible. |

| Central giant cell granuloma | Younger patients, anterior mandible, crosses midline. |

| Benign tumors or metastatic cancers | Rare, but must be considered if lesion fails to heal or enlarges. |

Summary Table: Common Periapical Lesions

| Lesion | Histology | Radiograph | Vitality | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granuloma | Chronic inflammation, granulation tissue | <1 cm radiolucency, well-circumscribed | Non-vital | RCT, monitor |

| Radicular Cyst | Epithelial-lined cavity with fluid/debris | >1 cm, round, corticated radiolucency | Non-vital | RCT; surgery if persistent |

| Periapical Abscess | Neutrophils, pus, necrosis | Poorly defined radiolucency (acute) | Non-vital | Drainage, RCT, antibiotics (if needed) |

| Condensing Osteitis | Sclerotic bone, low-grade inflammation | Radiopaque mass at apex | Non-vital | RCT; no surgery usually needed |

| Periapical Scar | Fibrous tissue, post-surgical healing | Persistent radiolucency, asymptomatic | Non-vital | Observe; biopsy if uncertain |

Clinical Features of Periapical Lesions

Periapical lesions present with a wide spectrum of clinical features, ranging from completely asymptomatic radiographic findings to severely painful, swelling-associated, and even systemic manifestations. Understanding the variation in symptoms and clinical signs is essential for correct diagnosis, timely intervention, and differential diagnosis from other orofacial pathologies.

Clinical features largely depend on the type of lesion (granuloma, cyst, or abscess), the stage of disease (acute vs chronic), and the host immune response.

Symptoms

A. Asymptomatic Presentation

Many periapical lesions, especially granulomas and cysts, develop insidiously and may remain asymptomatic for long periods. In fact, the majority of chronic lesions are identified incidentally on routine radiographs. Despite radiographic evidence of bone destruction at the apex, the patient may report no discomfort or functional limitation.

B. Pain

Pain is a hallmark of acute periapical inflammation and is most commonly associated with periapical abscesses or exacerbation of a chronic lesion.

Nature of pain:

Throbbing, persistent, and spontaneous.

Often localized but can radiate to adjacent areas.

Worsens with biting, chewing, or percussion.

Progression:

Initial dull ache may intensify into severe, sharp pain.

Pain may be relieved temporarily if drainage occurs via a sinus tract or periodontal ligament space.

C. Sensitivity to Biting or Percussion

This is a common feature in acute inflammatory stages and results from pressure within the periapical area.

- Vertical percussion: Frequently elicits discomfort.

- Tooth feels “high” or extruded: Due to edema in the periodontal ligament.

D. Swelling and Fluctuance

Soft tissue swelling may occur in acute infections, especially when the infection spreads beyond the bone into surrounding tissues.

- Swelling is usually firm in early stages, becoming fluctuant as pus accumulates.

- Location depends on the tooth involved and muscle attachments:

Maxillary infections: May cause facial swelling, infraorbital puffiness.

Mandibular molars: Can lead to buccal swelling, submandibular, or even sublingual space infections.

E. Sinus Tract or Fistula Formation

Chronic periapical abscesses often drain through a sinus tract either intraorally or extraorally.

- Intraoral sinus tract: Commonly opens on the attached gingiva or alveolar mucosa.

- Extraoral sinus tract: May be seen on the chin, cheek, or submandibular region.

- Sinus tracts are painless and often misdiagnosed as dermatological lesions.

F. Tooth Mobility

When periapical inflammation extends to involve the periodontal ligament or causes extensive bone loss, the affected tooth may become mobile.

- Usually associated with combined endo-perio lesions.

- Mobility increases in acute exacerbations due to edema.

G. Discoloration of the Affected Tooth

A discolored or darkened crown is often an indicator of pulp necrosis, particularly in previously traumatized teeth.

Suggests non-vital pulp even in absence of pain.

H. Bad Taste or Odor

When pus drains into the mouth from a sinus tract, patients may report a foul taste or halitosis.

Clinical Signs

A. Negative Pulp Vitality Tests

The affected tooth generally shows no response to cold, heat, or electric pulp testing, indicating a necrotic pulp.

- Must be interpreted with caution in multi-rooted teeth or young permanent teeth.

- Contralateral tooth can be used for comparison.

B. Tenderness on Palpation

Pressure over the apical area, facial or palatal/lingual vestibule may cause discomfort in acute conditions.

- Helps localize the affected tooth.

- In abscess cases, pus may be expressible upon palpation.

C. Presence of Swelling

- May be localized or diffuse.

- Fluctuation may indicate a drainable abscess.

- Induration indicates cellulitis or early abscess formation.

D. Lymphadenopathy

- Regional lymph nodes (submandibular, cervical) may be enlarged and tender in acute infections.

- Suggests spreading infection or systemic response.

E. Fever and Malaise

In severe or spreading infections, systemic signs such as fever, chills, malaise, and elevated WBC count may be present.

- Seen in aggressive abscesses or in immunocompromised patients.

- Requires prompt medical and dental intervention.

F. Trismus

- Infection involving posterior mandibular teeth may result in limited mouth opening, particularly if the masseter or pterygoid muscles are involved.

- Indicates fascial space involvement and needs urgent treatment.

G. Facial Asymmetry

- Especially in severe abscesses or cellulitis.

- Swelling alters normal facial contour.

Progression and Clinical Course

| Stage | Features |

|---|---|

| Initial Pulpal Inflammation | Reversible pulpitis, mild sensitivity to stimuli |

| Irreversible Pulpitis | Spontaneous pain, lingering thermal sensitivity |

| Pulp Necrosis | Tooth becomes asymptomatic, non-vital |

| Periapical Granuloma | Asymptomatic, radiolucency visible radiographically |

| Periapical Abscess | Severe pain, swelling, fever, pus formation |

| Chronic Abscess | Sinus tract formation, intermittent swelling and drainage |

| Systemic Spread | Cellulitis, fascial space infection, trismus, dysphagia, systemic symptoms |

Clinical Diagnostic Challenges

- Silent lesions may only be found via radiographs in routine exams.

- Symptom overlap between periodontal, periapical, and referred pain complicates diagnosis.

- Misdiagnosis can occur when extraoral sinus tracts are mistaken for skin infections.

- Multi-rooted teeth may have partial pulp necrosis – requiring testing of each canal.

Importance of Accurate Clinical Assessment

Correct interpretation of symptoms and clinical signs is essential to:

- Determine vitality status.

- Localize the source of pain or swelling.

- Decide between non-surgical and surgical treatment.

- Prevent over- or under-treatment (e.g., unnecessary extractions or missed canals).

- Avoid serious complications such as osteomyelitis, cellulitis, or cavernous sinus thrombosis.

Diagnostic Approaches for Periapical Lesions

Accurate diagnosis of periapical lesions is essential for effective treatment planning and successful outcomes. Despite the variety of lesion types, many periapical pathologies present with similar clinical and radiographic features. Therefore, a thorough, multi-faceted diagnostic approach is necessary to distinguish between them, determine the severity, and plan the appropriate course of action.

The diagnosis involves a combination of clinical evaluation, pulp vitality testing, radiographic interpretation, advanced imaging when needed, and, in selected cases, histopathological analysis.

Clinical Examination

The clinical assessment begins with a detailed history and physical examination of the affected tooth and surrounding structures.

A. History Taking

- Pain: Location, character (dull, sharp, throbbing), duration, and triggers.

- Swelling: Onset, progression, and presence of drainage.

- Previous dental work: Past trauma, restorations, or endodontic treatment.

- Systemic symptoms: Fever, malaise, facial swelling suggest abscess or cellulitis.

B. Extraoral Examination

- Look for facial asymmetry, palpable swelling, lymphadenopathy, or cutaneous sinus tracts.

- Examine TMJ and assess for trismus, especially in mandibular infections.

C. Intraoral Examination

Evaluate:

- Tooth mobility

- Tenderness to percussion (vertical and lateral)

- Palpation sensitivity in the buccal and lingual sulcus

- Presence of sinus tracts or fistulas

- Color change in the crown (may suggest necrosis)

Pulp Vitality Testing

Vitality testing helps determine the status of the pulp and is a key step in identifying the origin of the periapical pathology.

A. Thermal Testing

- Cold test (Endo-Ice or refrigerant sprays)

- Heat test (gutta-percha stick or hot water)

Interpretation:

- Positive but exaggerated: Reversible/irreversible pulpitis.

- No response: Necrotic pulp (strongly associated with periapical lesions).

B. Electric Pulp Test (EPT)

- Useful adjunct but less reliable than thermal tests.

- Measures sensory response but not pulp health.

- False positives/negatives common in young teeth, calcified canals, or recent trauma.

C. Selective Testing

- In multi-rooted teeth, test each canal or compare responses across adjacent teeth.

- Always test control teeth (contralateral or adjacent healthy teeth).

Radiographic Examination

Radiographs remain the primary tool for detecting and monitoring periapical lesions.

A. Intraoral Periapical Radiographs (IOPA)

- High-resolution image of tooth and periapical area.

- Taken using the paralleling technique for accurate interpretation.

Typical features of periapical lesions:

- Loss of lamina dura at the apex.

- Periapical radiolucency or radiopacity.

- Poorly defined margins in acute lesions; well-defined in chronic ones.

- Cystic lesions may show corticated borders and expansion.

B. Bitewing Radiographs

Better for detecting interproximal decay and restoration defects, but less effective for periapical evaluation.

C. Limitations

- Two-dimensional images may miss buccal/lingual extension.

- Cannot reliably differentiate between cyst, granuloma, or abscess.

- May not detect early-stage lesions due to insufficient bone loss.

Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT)

Overview

CBCT is a three-dimensional imaging modality that offers improved accuracy in diagnosing periapical pathologies, particularly when conventional radiographs are inconclusive.

Advantages

3D visualization of lesion size, volume, and location.

Superior in detecting:

Buccolingual bone loss.

Missed canals or perforations.

Root fractures.

Early periapical changes before radiographic visibility.

Clinical Applications

- Distinguishing between true cysts and granulomas (though not always definitive).

- Evaluating lesions associated with previously treated teeth.

- Planning surgical endodontic procedures.

Limitations

- Higher radiation dose than standard radiographs.

- Higher cost and less availability.

- Interpretation complexity; requires training and experience.

Sinus Tract Tracing

When a sinus tract is present, tracing it can help localize the origin of the infection.

Procedure:

- Insert a gutta-percha point into the tract until resistance is met.

- Take a periapical radiograph.

- The tip of the gutta-percha often points to the culprit tooth apex.

Periodontal Probing and Mobility Testing

Differentiates endo-perio lesions from purely endodontic or periodontal origins.

- Isolated deep pocket: Suggests vertical root fracture or draining sinus.

- Generalized pockets: More consistent with periodontal disease.

- Combined pockets: Could indicate a combined lesion needing complex therapy.

Histopathological Examination

Histologic evaluation is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis but is only feasible when tissue is surgically removed (e.g., during apicoectomy or biopsy).

Indications

- Lesion does not heal after appropriate endodontic treatment.

- Atypical features suggest neoplasm or non-endodontic pathology.

- Rapid lesion growth or unusual location (e.g., anterior mandible).

Features Identified

- Periapical granuloma: Granulation tissue, chronic inflammatory cells.

- Radicular cyst: Epithelial lining, fluid-filled cavity.

- Abscess: Pus, necrotic debris, neutrophilic infiltration.

Differential Diagnosis

It is essential to differentiate periapical lesions of endodontic origin from other pathologies that mimic their appearance.

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Cemento-osseous dysplasia | Vital tooth, mixed radiolucent/opaque lesions, often in African females |

| Central giant cell granuloma | Crosses midline, younger patients, aggressive expansion |

| Odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) | Well-defined radiolucency, often posterior mandible, recurrence risk |

| Ameloblastoma | Multilocular radiolucency, root resorption, bony expansion |

| Metastatic tumors | Rapid growth, paresthesia, poor prognosis |

| Nasopalatine duct cyst | Midline maxillary radiolucency between central incisors |

| Periodontal abscess | Vital pulp, localized periodontal defect, lateral radiolucency |

Laboratory Tests (in Selected Cases)

Though rarely required for routine cases, some tests may be useful in atypical or systemic presentations:

- CBC with differential: Elevated WBC in systemic infections.

- C-reactive protein (CRP) or ESR: May indicate inflammation severity.

- Blood glucose: To assess for poorly controlled diabetes in non-healing cases.

Diagnostic Checklist Summary

| Step | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Clinical exam | Identify symptoms, sinus tracts, swelling, discoloration |

| Vitality testing | Determine pulp status |

| Radiographic evaluation | Detect periapical changes, size, and bone loss |

| CBCT (if indicated) | 3D visualization, detect complex anatomy or early bone changes |

| Sinus tract tracing | Localize source of chronic drainage |

| Periodontal exam | Rule out periodontal origin or combined lesions |

| Histopathology | Confirm lesion type when surgically removed |

Periapical Lesion Treatment

Effective management of periapical lesions involves eliminating the source of infection, facilitating healing of periapical tissues, and restoring the tooth to function and health. The treatment approach depends on multiple factors including lesion type (granuloma, cyst, abscess), lesion size, vitality of the pulp, presence of symptoms, and previous treatment history.

The overarching goals of treatment are to:

- Eradicate the infection within the root canal system.

- Promote regeneration of periapical bone.

- Prevent recurrence by sealing all portals of bacterial entry.

Non-Surgical Root Canal Therapy (NSRCT)

Non-surgical root canal treatment is the first-line therapy for most teeth with periapical lesions, regardless of whether the lesion is a granuloma, abscess, or a cyst (in many cases).

Indications

- Non-vital teeth with periapical radiolucencies.

- Persistent periapical lesions in previously untreated teeth.

- Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic teeth.

Objectives

- Remove infected/necrotic pulp tissue.

- Thoroughly debride, shape, and disinfect the root canal system.

- Obturate (seal) the canal space hermetically to prevent recontamination.

Treatment Protocol

Access and canal location

Biomechanical preparation using hand or rotary files.

Irrigation with antimicrobial agents (e.g., sodium hypochlorite, chlorhexidine).

Intracanal medicament placement (commonly calcium hydroxide) between appointments to:

Reduce bacterial load.

Stimulate hard tissue repair.

Dissolve necrotic debris.

Obturation with gutta-percha and sealer.

Definitive coronal restoration to prevent microleakage.

Outcomes

- Most periapical granulomas and pocket cysts heal within 6–12 months post-treatment.

- Radiographic healing may take up to 2 years.

- True cysts may resist healing due to their self-sustaining nature.

Re-Treatment of Failed Root Canal Therapy

Retreatment may be required if:

- Inadequate initial root canal therapy was performed (missed canals, underfilled canals, poor obturation).

- A periapical lesion persists or enlarges.

- Coronal leakage compromised the seal.

Steps

- Removal of old obturation materials.

- Identification of missed canals.

- Re-instrumentation, disinfection, and re-obturation.

- Use of modern techniques (e.g., ultrasonics, CBCT imaging) improves success.

Success Rate

Approximately 70–80% if all causes of failure are addressed.

Surgical Endodontic Treatment (Apical Surgery / Apicoectomy)

Apical surgery is indicated when non-surgical retreatment is not feasible or has failed.

Indications

- Persistent periapical lesion after competent NSRCT or retreatment.

- True cysts (not connected to canal).

- Anatomic complexities (e.g., calcified canals, separated instruments).

- Root-end perforations, fractures, or external resorption.

- Patient preference to retain a strategically important tooth.

Procedure Steps

- Flap reflection to expose the periapical area.

- Curettage and removal of the lesion.

- Apicoectomy: Resection (typically 3 mm) of the root tip.

- Retrograde preparation and filling using materials like MTA (mineral trioxide aggregate).

- Histopathologic analysis of removed tissue (recommended).

Success Rate

Over 90% when performed with modern microsurgical techniques and biocompatible materials.

Incision and Drainage

Reserved for acute periapical abscesses with significant swelling and pus accumulation.

Procedure

- Small incision into the fluctuant area under local anesthesia.

- Blunt dissection and drainage of pus.

- Placement of a drain (e.g., rubber dam strip) if needed.

Adjunctive Measures

- Antibiotics for systemic symptoms (see next section).

- Pain control with NSAIDs or other analgesics.

Antibiotic Therapy

Antibiotics are not routinely required for localized periapical infections. They are used in conjunction with mechanical treatment when:

Indications

- Fever (>38°C)

- Malaise or systemic involvement

- Diffuse facial swelling (cellulitis)

- Involvement of fascial spaces

- Immunocompromised patients

Common Antibiotics

- Amoxicillin: First-line, 500 mg TID for 5–7 days.

- Clindamycin: 300 mg QID for penicillin-allergic patients.

- Metronidazole: For anaerobic coverage, often combined with amoxicillin.

Tooth Extraction

Extraction may be considered when:

- The tooth is non-restorable due to structural damage or advanced caries.

- Severe periodontal disease compromises the prognosis.

- Lesion fails to resolve despite root canal therapy and retreatment.

- Patient preference or financial considerations.

After extraction:

- Curettage of granulation or cystic tissue should be performed.

- Bone grafting may be considered if implant placement is planned.

Regenerative Endodontic Therapy (RET)

A modern biologic treatment approach especially useful in immature permanent teeth with necrotic pulps.

Goals

- Eliminate infection.

- Promote continued root development (thickening of dentinal walls and apical closure).

- Restore vitality via regeneration of pulp-like tissue.

Key Steps

- Disinfection of the canal with low-concentration irrigants and antibiotic paste.

- Induce bleeding into the canal to create a blood clot (scaffold).

- Place biocompatible matrix (e.g., MTA) over the clot.

- Seal and restore.

Outcomes

- Radiographic evidence of root growth.

- Positive vitality response in some cases.

- High success in young teeth with wide apices.

Follow-Up and Monitoring

Timelines

- Initial follow-up: 6 months post-treatment.

- Subsequent radiographs: Annually until full resolution or stability.

Radiographic Signs of Healing

- Gradual reduction in size of radiolucency.

- Reappearance of lamina dura.

- Normal trabecular bone pattern.

Signs of Treatment Failure

- Persistent or enlarging lesion.

- Pain or reinfection.

- Sinus tract formation.

Factors Affecting Treatment Outcomes

| Positive Predictors | Negative Predictors |

|---|---|

| Proper canal disinfection | Missed canals |

| Good coronal seal | Persistent leakage or reinfection |

| Early intervention | Delay in treatment |

| Host immune competence | Immunosuppression or systemic disease |

| Accurate diagnosis and treatment planning | Failure to address etiology or anatomical issues |

Summary of Treatment Options for Periapical Lesions

| Lesion Type | First-line Treatment | Alternate/Surgical Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Granuloma | Non-surgical root canal therapy | Apicoectomy (if persistent) |

| Radicular cyst | NSRCT (if pocket cyst) | Surgical enucleation for true cysts |

| Abscess (acute) | I&D, NSRCT, antibiotics if needed | Extraction (if tooth is non-restorable) |

| Chronic abscess | Root canal treatment and sinus tract tracing | Apical surgery (if lesion persists) |

| Failed RCT lesion | Non-surgical retreatment | Apicoectomy or extraction |

| Immature necrotic teeth | Regenerative endodontics | Apexification or extraction |

Prognosis and Healing

The prognosis of periapical lesions—whether a granuloma, cyst, or abscess—is generally favorable with proper endodontic intervention. Healing is a biological process involving the resolution of infection, inflammation, and gradual regeneration of periapical tissues, including alveolar bone.

Several factors influence the outcome of treatment, and understanding the dynamics of healing allows clinicians to monitor progress, detect complications early, and make informed decisions regarding further management.

Healing Mechanisms of Periapical Lesions

Once the etiological factor (usually pulp-derived infection) is removed through effective root canal treatment, the body initiates healing processes that include:

A. Inflammation Resolution

- Removal of bacterial toxins allows for cessation of chronic inflammation.

- Inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes) decrease in number.

- Cytokines and enzymes (e.g., prostaglandins, MMPs) responsible for bone resorption are downregulated.

B. Bone Regeneration

- Osteoblasts begin laying down new bone matrix.

- Resorbed bone is replaced by healthy trabecular bone over time.

- The lamina dura (radiopaque line surrounding the tooth root) reappears as a sign of complete healing.

C. Fibrous Tissue Healing

- In some cases, a periapical scar may form—especially when extensive surgical intervention occurred, or cortical bone was destroyed.

- Although radiographically visible, it is non-pathologic and asymptomatic.

Healing Timelines

The rate of healing varies depending on lesion type, size, and patient-specific factors.

| Time Frame | Expected Healing Changes |

|---|---|

| 0–3 months | Resolution of symptoms, sinus tract closure, early bone fill visible |

| 3–6 months | Radiographic evidence of reduced lesion size, signs of bone remodeling |

| 6–12 months | Continued bone regeneration; lesion may appear significantly smaller |

| 12–24 months | Complete radiographic resolution in most cases (especially granulomas) |

| >2 years | Some cysts or large lesions may take longer; persistent radiolucency may warrant further investigation |

Prognosis by Lesion Type

| Lesion | Healing Potential | Typical Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Granuloma | High, with conservative treatment | Resolves in >90% of cases post-RCT |

| Pocket Cyst | High, if infection is eliminated | May resolve without surgery |

| True Cyst | Moderate to low without surgery | Often requires surgical removal |

| Abscess | High after drainage and root canal therapy | Rapid symptomatic relief; gradual bone healing |

| Chronic abscess | High; sinus tract resolves with treatment | Monitor to confirm tract closure |

| Periapical scar | Static non-pathological condition | No treatment needed if asymptomatic |

Factors Influencing Healing

A. Patient Factors

- Age: Younger patients often heal faster due to higher bone turnover.

- Systemic health: Diabetes, immunosuppression, and smoking delay healing.

- Nutrition and compliance: Poor oral hygiene and irregular follow-up reduce prognosis.

B. Lesion-Related Factors

- Size of the lesion: Larger lesions may require more time to heal.

- Cystic vs granulomatous: Cysts take longer and may not respond to conservative treatment.

- Duration: Chronic lesions may induce structural changes (e.g., epithelial lining) that slow healing.

C. Treatment Factors

- Disinfection quality: Inadequate canal debridement leads to persistent infection.

- Missed anatomy: Untreated accessory or lateral canals can harbor bacteria.

- Quality of obturation: Voids or underfilling compromise seal and healing.

- Coronal restoration: Poor sealing allows reinfection of root canal space.

Clinical and Radiographic Signs of Healing

Clinical Signs

- Absence of pain, swelling, and tenderness.

- Normal function restored to the tooth.

- Closure of any sinus tract (if previously present).

- No mobility beyond normal physiologic range.

Radiographic Signs

- Progressive reduction in size of the radiolucent lesion.

- Reappearance of the lamina dura.

- Return of normal trabecular bone pattern.

- Sharper radiographic definition of periapical structures.

Indicators of Healing Failure or Complications

A lesion may fail to heal despite apparently adequate treatment. Warning signs include:

- Persistence or increase in size of periapical radiolucency.

- Persistent symptoms: pain, sensitivity, sinus tract.

- New swelling or development of cellulitis.

- Unfavorable histological diagnosis (e.g., neoplasm, giant cell granuloma).

- Tooth fracture or vertical root fracture detected during follow-up.

Causes of failure may include:

- Incomplete disinfection or missed canals.

- Leakage through coronal restoration.

- Resistant microorganisms (e.g., Enterococcus faecalis).

- Foreign body reactions (e.g., extruded filling materials).

- Incorrect diagnosis (e.g., non-endodontic lesion misdiagnosed as periapical pathology).

Monitoring and Follow-Up Protocols

Timeline

- Initial follow-up: 3–6 months after treatment.

- Subsequent intervals: Every 6–12 months for at least 2 years.

Imaging Strategy

- Periapical radiographs: Sufficient in most cases.

- CBCT: Reserved for lesions that do not resolve or are suspicious for other pathologies.

Documentation

- Record clinical findings, test responses, and radiographic changes.

- Consider photographic records of sinus tracts or swelling at baseline.

When to Intervene Further

If healing does not progress or symptoms persist, the clinician must reassess the case.

Options include:

- Non-surgical retreatment: Especially if initial treatment was substandard.

- Surgical endodontics: If retreatment is not feasible or lesion is cystic.

- Extraction: If prognosis is poor due to structural or periodontal issues.

- Biopsy: For non-healing lesions to rule out neoplasms or atypical pathology.

Prognostic Indicators in Literature

- Teeth treated with modern root canal techniques show success rates of 85–95% in periapical healing.

- Lesions treated with microsurgical apicoectomy using biocompatible materials (like MTA or bioceramics) achieve success rates above 90%.

- Regenerative endodontic procedures in immature teeth show radiographic evidence of root maturation in 70–90% of cases.