Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most prevalent form of arthritis, affecting millions of people worldwide. Characterized by the gradual degeneration of joint cartilage and the underlying bone, OA typically leads to pain, stiffness, decreased mobility, and a decline in quality of life. Unlike some other forms of arthritis, osteoarthritis is not primarily driven by inflammation but rather by mechanical wear and tear. Though often associated with aging, OA can affect individuals of all ages due to a variety of risk factors, including genetics, obesity, joint injuries, and overuse.

Table of Contents

TogglePathophysiology of Osteoarthritis

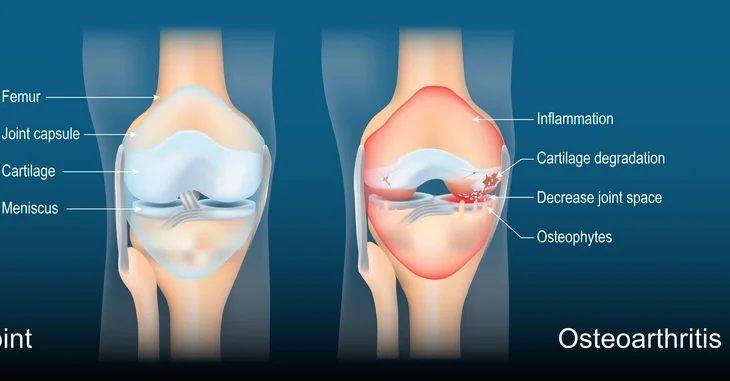

Osteoarthritis primarily involves the progressive deterioration of articular cartilage, which is the smooth, resilient tissue that covers and cushions the ends of bones in synovial joints. Healthy cartilage facilitates low-friction movement and acts as a shock absorber during joint activity. In OA, this cartilage gradually breaks down, resulting in exposed bone surfaces that rub together, leading to mechanical pain, joint stiffness, and impaired function.

In the early stages of OA, changes occur at the molecular and cellular levels within the cartilage. Chondrocytes, the primary cells of cartilage, are responsible for maintaining the extracellular matrix, which consists of collagen and proteoglycans. In OA, chondrocytes enter a state of dysfunction, where they increase the production of degradative enzymes like matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and aggrecanases. These enzymes break down collagen and proteoglycans, resulting in a net loss of cartilage matrix.

Simultaneously, inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) are upregulated in the joint environment. Although OA is not primarily an inflammatory arthritis like rheumatoid arthritis, low-grade inflammation still plays a crucial role in cartilage degradation. These cytokines stimulate chondrocytes and synoviocytes to release further degradative enzymes, creating a feedback loop that accelerates cartilage loss.

As cartilage wears away, the subchondral bone underneath it becomes exposed and undergoes structural changes. Increased bone turnover leads to sclerosis (hardening), and microfractures can develop, contributing to joint pain. The joint attempts to stabilize itself through bone remodeling, which often results in the formation of osteophytes (bony outgrowths) at the joint margins.

The synovial membrane, which lines the joint capsule and produces synovial fluid for lubrication, may become mildly inflamed and hypertrophic. This inflammation contributes to joint swelling and further cytokine release. In some cases, the joint capsule and surrounding ligaments also become less elastic and more fibrotic, further limiting joint mobility.

Another notable feature of OA pathophysiology is the deterioration of menisci in the knee and labrum in the hip, both of which are fibrocartilaginous structures that contribute to joint stability and load distribution. Their degeneration exacerbates joint instability and increases mechanical stress on articular cartilage.

Overall, the pathophysiology of OA is a complex interplay of mechanical, cellular, biochemical, and inflammatory processes. The disease represents a failure of joint homeostasis, where reparative processes are insufficient to counterbalance the destructive mechanisms.

Risk Factors for Osteoarthritis

There is no single cause of osteoarthritis; rather, it arises from a combination of risk factors that contribute to joint degeneration over time:

- Age: The risk of developing OA increases with age due to the cumulative effects of mechanical stress and biochemical changes in cartilage composition and repair capacity. Aging cartilage is less resilient and more susceptible to damage.

- Gender: Women, particularly postmenopausal women, are at a higher risk for OA. Hormonal changes, especially a decline in estrogen, are believed to affect cartilage metabolism and joint integrity.

- Genetics: Family history plays a significant role in OA risk. Specific genetic variants have been linked to cartilage structure, inflammatory response, and bone density, all of which influence OA development. Inherited traits may predispose individuals to earlier onset or more severe forms of OA.

- Obesity: Excess body weight significantly increases the load on weight-bearing joints, such as the knees and hips. Moreover, adipose tissue is metabolically active and secretes inflammatory mediators (adipokines) that can contribute to systemic inflammation and joint degradation.

- Joint Injuries: Traumatic injuries, such as ligament tears, meniscal damage, or fractures near joints, can disrupt joint mechanics and increase OA risk. Even injuries that are properly treated may lead to OA years later due to altered joint loading and instability.

- Repetitive Stress: Occupations and sports involving repetitive joint use or high-impact activities can accelerate wear and tear on cartilage. Examples include frequent kneeling, squatting, heavy lifting, or prolonged standing.

- Bone Deformities and Joint Abnormalities: Congenital conditions such as hip dysplasia, or developmental issues like malalignment of joints, can predispose individuals to abnormal joint loading and increased OA risk.

- Muscle Weakness: Inadequate muscle strength, particularly around key joints like the knees, can compromise joint stability and function, leading to increased mechanical stress on cartilage.

- Metabolic Disorders: Conditions like diabetes and hyperlipidemia are associated with systemic inflammation and may play a role in the pathogenesis of OA. Metabolic syndrome has been linked to increased OA prevalence.

- Previous Joint Surgery: Surgical procedures involving joints, especially those altering joint structure or mechanics (e.g., meniscectomy), may predispose the joint to accelerated degeneration.

Understanding and managing these risk factors through lifestyle modifications, medical interventions, and preventive strategies is key to reducing the onset and progression of OA.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

Osteoarthritis symptoms can vary widely depending on the affected joint and the severity of the condition. Symptoms usually develop gradually and worsen over time. Recognizing early signs is important for timely intervention. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Joint Pain: The hallmark symptom of OA, typically described as a deep, aching pain that worsens with joint use and improves with rest. In advanced stages, pain may persist even during rest or at night.

- Stiffness: Most pronounced after periods of inactivity, such as waking in the morning or after sitting for long durations. This morning stiffness usually lasts less than 30 minutes.

- Swelling and Inflammation: Swelling may occur due to joint effusion (fluid accumulation) or synovial inflammation, contributing to discomfort and reduced range of motion.

- Reduced Flexibility and Range of Motion: As cartilage degrades and joint space narrows, the ability to move the joint freely diminishes, impacting daily activities such as walking, bending, or gripping objects.

- Joint Instability or Buckling: Weakened muscles and ligament laxity may lead to feelings of the joint “giving way,” particularly in weight-bearing joints like the knees.

- Crepitus: A grinding, clicking, or popping sensation that occurs with joint movement due to irregular joint surfaces and bone-on-bone contact.

- Tenderness: Sensitivity or pain when pressing on or around the joint.

- Bone Spurs (Osteophytes): Bony enlargements that develop along the edges of the joint and may be visible or palpable, contributing to joint stiffness and deformity.

Joint-Specific Presentations:

- Hands: OA in the hands often affects the distal interphalangeal (DIP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) joints. Symptoms include joint enlargement, reduced grip strength, and the formation of Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes.

- Knees: Knee OA can cause pain during activities like walking or climbing stairs. Swelling, stiffness, and a reduced ability to fully bend or straighten the knee are common.

- Hips: Hip OA may result in groin pain that radiates to the thigh or buttocks, difficulty with walking, and trouble with activities like getting in and out of a car.

- Spine: OA in the cervical or lumbar spine may lead to localized pain, stiffness, and nerve compression symptoms such as numbness or tingling in the limbs.

Because OA symptoms can overlap with other joint disorders, accurate assessment is crucial for effective treatment. Identifying which joints are involved and understanding the nature and pattern of symptoms helps guide diagnosis and management.

Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis

Diagnosing osteoarthritis requires a comprehensive approach that incorporates clinical evaluation, imaging techniques, and laboratory tests to rule out other possible causes of joint symptoms.

Medical History: A thorough history is essential and includes the duration, nature, and pattern of joint pain and stiffness, functional limitations, previous joint injuries, occupational and recreational activities, and family history of arthritis.

Physical Examination: Clinicians assess for joint tenderness, swelling, bony enlargements, crepitus, range of motion limitations, joint alignment, and muscle strength. Functional assessments may include gait analysis and observing how a patient performs daily activities.

Imaging Studies:

X-rays are the most common imaging tool and can reveal joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation, subchondral sclerosis, and cysts.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is more sensitive for early detection and can assess cartilage thickness, bone marrow lesions, meniscal damage, and soft tissue involvement.

Ultrasound may be used to evaluate joint effusions, synovial thickening, and inflammation in real-time, especially in peripheral joints.

Laboratory Tests:

While there are no specific blood tests for OA, basic labs (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP], rheumatoid factor [RF], and anti-CCP antibodies) help exclude inflammatory or autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis.

Joint fluid analysis may be performed in cases of joint swelling to rule out gout, pseudogout, or infection. OA synovial fluid is typically clear, yellow, and of low viscosity with low white cell count.

Accurate diagnosis is crucial not only to confirm OA but also to determine the stage of disease, guide treatment decisions, and differentiate from other joint conditions.

Staging of Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis staging helps clinicians determine the severity of the disease and guide treatment decisions. The most widely used classification system is the Kellgren Lawrence grading scale, based on radiographic findings. Staging can also incorporate clinical symptoms and functional impairments. The five general stages are:

Stage 0 (Normal):

- No clinical or radiographic signs of osteoarthritis.

- Joint appears healthy.

Stage 1 (Minor):

- Minor bone spur (osteophyte) formation.

- No significant joint space narrowing.

- Little or no pain or functional limitation.

- Preventive strategies may be beneficial.

Stage 2 (Mild):

- Noticeable bone spur formation.

- Joint space begins to narrow.

- Cartilage shows early signs of wear.

- Patients may experience discomfort after prolonged activity.

- Conservative treatment (e.g., exercise, weight loss) is recommended.

Stage 3 (Moderate):

- Significant joint space narrowing.

- Erosion of cartilage becomes evident.

- Osteophytes increase in size and number.

- Pain becomes more frequent and may affect daily activities.

- Functional impairments begin to emerge.

- Pharmacological interventions may be needed.

Stage 4 (Severe):

- Drastic reduction or complete loss of joint space.

- Extensive cartilage destruction and large osteophyte formation.

- Chronic inflammation and pronounced joint deformity.

- Severe pain even during rest.

- Substantial loss of function and mobility.

- Surgical options like joint replacement may be considered.

Understanding the stage of OA is crucial for designing an individualized treatment plan and setting realistic expectations for outcomes.

Treatment Options for Osteoarthritis

There is no cure for osteoarthritis, but a broad spectrum of treatment options is available to help manage symptoms, enhance joint function, and slow disease progression. The choice of treatment depends on the severity of the disease, the specific joints affected, patient preferences, and overall health status. Management is typically multidisciplinary, involving healthcare providers such as primary care physicians, rheumatologists, physical therapists, and orthopedic surgeons.

Non-Pharmacological Treatments

Non-drug interventions form the foundation of OA management and are essential for all stages of the disease.

- Weight Management: Weight loss is critical for overweight or obese individuals, as it reduces mechanical load on weight-bearing joints such as the knees and hips. Even modest weight loss can significantly alleviate pain and improve function.

- Exercise and Physical Activity: Regular low-impact aerobic exercises (e.g., walking, swimming, cycling) combined with strength training improve joint mobility, muscle strength, and overall function. Stretching and flexibility exercises also help maintain the range of motion.

- Physical and Occupational Therapy: Physical therapists design personalized exercise regimens to strengthen joint-supporting muscles and reduce pain. Occupational therapists help patients adapt daily tasks and use joint-protective techniques.

- Assistive Devices: Braces, orthotic shoe inserts, canes, walkers, and ergonomic tools can support joints, improve stability, and reduce discomfort during movement.

- Hot and Cold Therapy: Application of heat can relax muscles and improve circulation, while cold therapy helps reduce joint swelling and pain.

- Complementary Therapies: Acupuncture, massage therapy, and tai chi have shown benefits in managing OA symptoms for some individuals, though evidence varies.

- Patient Education and Self-Management Programs: Educating patients about OA, its progression, and self-care strategies empowers them to take an active role in managing their condition.

Pharmacological Treatments

When non-pharmacological measures are insufficient, medications are introduced to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Acetaminophen (Paracetamol): Often recommended for mild to moderate OA pain. It has fewer gastrointestinal side effects compared to NSAIDs but may be less effective.

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Include ibuprofen, naproxen, and diclofenac. They provide both analgesic and anti-inflammatory benefits but may cause gastrointestinal, renal, or cardiovascular side effects with long-term use.

- Topical NSAIDs: Creams or gels applied directly to the skin over affected joints (e.g., diclofenac gel) are effective, particularly for hand and knee OA, and carry fewer systemic risks.

- Capsaicin Cream: Derived from chili peppers, capsaicin can reduce pain by depleting substance P from nerve endings.

- Duloxetine: A serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) that may help relieve chronic musculoskeletal pain, including OA-related pain.

- Corticosteroid Injections: Intra-articular steroid injections provide temporary relief of inflammation and pain, especially in advanced OA. They are not recommended for frequent, long-term use due to potential cartilage damage.

- Hyaluronic Acid Injections: Viscosupplementation aims to restore joint lubrication. Evidence on effectiveness is mixed, and benefits may be modest or variable.

- Supplements: Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are popular supplements, but scientific support for their efficacy is inconsistent. They are generally safe but should be used with realistic expectations.

Surgical Interventions

Surgery is typically reserved for patients with severe OA who do not respond adequately to conservative measures.

- Arthroscopy: Minimally invasive procedure to clean the joint space. Once common, its benefit in OA is now considered limited, especially for long-term outcomes.

- Osteotomy: Realignment of bones to redistribute load across the joint. It is more common in younger patients with knee OA.

- Joint Replacement (Arthroplasty): Partial or total joint replacement is a highly effective intervention for advanced OA, especially in the hips and knees. It significantly reduces pain and restores mobility. Post-operative rehabilitation is essential for optimal recovery.

- Joint Fusion (Arthrodesis): Involves fusing bones in severely damaged joints, commonly used in small joints like those in the hand or foot when joint replacement is not feasible.

Combining different therapies based on disease severity and patient response can provide the most effective symptom control and quality of life improvement. Multidisciplinary collaboration and individualized treatment plans are key to optimal OA management.

Emerging Treatments and Research

Research in osteoarthritis is rapidly evolving, with promising new therapies and approaches:

- Disease-Modifying Osteoarthritis Drugs (DMOADs): These aim to slow or reverse joint degeneration. Some drugs target inflammatory pathways or stimulate cartilage regeneration.

- Regenerative Medicine: Stem cell therapy and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) are being investigated for their potential to repair damaged cartilage.

- Gene Therapy: Aiming to modify the expression of genes involved in cartilage degradation and inflammation.

- Biomarkers: Identifying molecular markers to diagnose OA early and monitor disease progression.

- Pain Management Innovations: Novel pain relief mechanisms, including monoclonal antibodies targeting nerve growth factor (NGF), are in development.

Living with Osteoarthritis

Managing OA requires a holistic, long-term approach that includes both medical treatment and lifestyle adaptations. Support from healthcare providers, caregivers, and peer support groups can significantly improve patient outcomes.

Tips for Daily Living:

- Maintain a regular exercise routine to keep joints flexible.

- Use ergonomic tools to reduce strain on joints.

- Modify home and work environments for safety and comfort.

- Practice stress management techniques, as chronic pain can affect mental health.