Lymphoma is a type of cancer that originates in the lymphatic system, a vital part of the immune system that helps the body fight infections and maintain fluid balance. It develops when lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) undergo abnormal changes, multiply uncontrollably, and accumulate in lymph nodes or other tissues.

Unlike some cancers that have clear environmental or lifestyle causes, lymphoma can affect people of all ages, often without obvious risk factors. Because it encompasses a broad range of subtypes with different prognoses and treatment strategies, understanding lymphoma requires exploring both its biological complexity and its clinical diversity.

Table of Contents

ToggleOverview of the Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system is a network of tissues and organs that help rid the body of toxins, waste, and other unwanted materials. It includes:

- Lymph nodes: Small, bean-shaped structures that filter lymph fluid and house immune cells.

- Lymphatic vessels: Thin tubes that carry lymph fluid throughout the body.

- Spleen: Helps filter blood and fight infections.

- Thymus: Plays a role in T-cell development.

- Tonsils and adenoids: Trap pathogens from the nose and mouth.

- Bone marrow: Produces lymphocytes and other blood cells.

Lymphocytes themselves come in two main types:

- B cells (B lymphocytes): Produce antibodies to neutralize pathogens.

- T cells (T lymphocytes): Destroy infected or abnormal cells and help regulate immune responses.

When either of these cell types mutates and begins to proliferate uncontrollably, lymphoma can develop.

Types of Lymphoma

Lymphomas are broadly divided into two main categories:

Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL)

First described by Dr. Thomas Hodgkin in 1832, Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by the presence of Reed–Sternberg cells, large abnormal B lymphocytes with distinctive microscopic features. HL accounts for about 10% of all lymphoma cases.

Subtypes include:

- Nodular sclerosis HL (most common)

- Mixed cellularity HL

- Lymphocyte-rich HL

- Lymphocyte-depleted HL

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL (NLPHL), which behaves differently from classic HL

HL is often considered one of the most curable forms of cancer, especially when diagnosed early.

Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL)

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma encompasses a much larger and more diverse group of lymphoid cancers—over 60 distinct subtypes. These are classified by cell origin (B cell, T cell, or NK cell), growth rate, and other molecular features.

Common B-cell lymphomas:

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) — most common and aggressive form

- Follicular lymphoma — slow-growing (indolent)

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Burkitt lymphoma — fast-growing, requires urgent treatment

- Marginal zone lymphoma

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL)

Common T-cell lymphomas:

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL)

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL)

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) such as mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

The behavior of NHL ranges from indolent (slow-growing, often monitored without immediate treatment) to highly aggressive (requiring prompt intervention).

Causes and Risk Factors

The exact cause of lymphoma is not always identifiable, but several factors can increase risk:

- Genetic mutations: Changes in DNA that affect cell growth regulation.

- Immune system compromise: HIV/AIDS, organ transplant recipients, and people with autoimmune diseases are at higher risk.

- Infections: Certain viruses and bacteria (e.g., Epstein–Barr virus, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1, Helicobacter pylori) are linked to specific lymphoma types.

- Family history: A slight increase in risk if a close relative has lymphoma.

- Chemical exposure: Pesticides, solvents, and other industrial chemicals may play a role.

- Age and gender: HL is more common in younger adults (15–40) and older adults (55+), while NHL risk increases with age.

Symptoms of Lymphoma

Lymphoma symptoms can be subtle or mistaken for less serious conditions, making early diagnosis challenging.

Common signs and symptoms include:

- Painless swelling of lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin

- Unexplained fever

- Drenching night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss (more than 10% of body weight over 6 months)

- Persistent fatigue

- Itching (pruritus) without rash

- Loss of appetite

- In some cases, pain in lymph nodes after alcohol consumption (more specific to HL)

- Symptoms from organ involvement, such as coughing or chest pain if lymph nodes press on airways

Diagnosis

A suspected lymphoma diagnosis requires careful evaluation:

Physical examination — Checking for enlarged lymph nodes, spleen, or liver.

Blood tests — Including complete blood count, LDH levels, liver and kidney function.

Imaging:

CT scans

PET scans (useful for staging and treatment monitoring)

MRI in certain cases

Lymph node biopsy — Gold standard for diagnosis; allows microscopic and immunohistochemical analysis.

Bone marrow biopsy — Determines whether lymphoma has spread.

Molecular testing — Detects genetic mutations and guides targeted therapies.

Staging

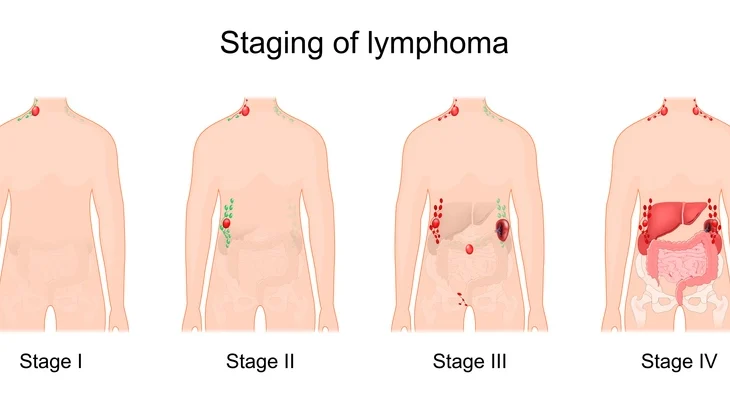

The Ann Arbor staging system (with Cotswolds modification) is commonly used:

- Stage I: One lymph node region or one extralymphatic site.

- Stage II: Two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm.

- Stage III: Lymph node involvement on both sides of the diaphragm.

- Stage IV: Widespread involvement, including bone marrow or other organs.

Stages are further classified with A (no systemic symptoms) or B (presence of fever, night sweats, weight loss).

Treatment Options

Lymphoma treatment is highly individualized, depending on the lymphoma subtype, stage, growth rate, genetic features, patient’s overall health, and personal preferences. Modern approaches often combine several treatment modalities to achieve the best results, aiming either for cure (especially in aggressive types) or long-term disease control (for many indolent types).

Below is an expanded look at the main treatment strategies:

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy remains the cornerstone of lymphoma treatment, especially for aggressive types. It involves the use of cytotoxic drugs that target rapidly dividing cells, including cancer cells.

How it works:

Chemotherapy agents interfere with cell division by damaging DNA, disrupting microtubule function, or inhibiting enzymes necessary for replication. While this harms cancer cells, it can also affect normal cells like hair follicles, bone marrow, and the lining of the gut—leading to side effects.

Common regimens:

- ABVD: Adriamycin (doxorubicin), Bleomycin, Vinblastine, Dacarbazine — standard for Hodgkin lymphoma.

- BEACOPP: More intensive regimen for advanced HL.

- CHOP: Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, Prednisone — often used in NHL, especially diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

- R-CHOP: CHOP + Rituximab (for CD20-positive B-cell lymphomas).

- Hyper-CVAD: Alternating cycles of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, and high-dose methotrexate/cytarabine — for very aggressive lymphomas like Burkitt lymphoma.

Side effects:

- Hair loss, nausea, fatigue, mouth sores

- Suppressed immunity (risk of infection)

- Low blood counts (anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia)

- Potential heart or lung toxicity (especially with doxorubicin and bleomycin)

- Fertility effects (important for younger patients — sperm/egg preservation may be discussed before treatment)

Supportive measures:

- Antiemetics (to control nausea)

- Growth factors like G-CSF (to boost white blood cells)

- Prophylactic antibiotics or antivirals in immunosuppressed patients

Radiation Therapy (RT)

Radiation uses high-energy beams to destroy cancer cells in targeted areas.

When used:

- As a primary treatment for localized, early-stage HL or indolent NHL

- After chemotherapy (consolidation therapy) to eliminate residual disease

- Palliative treatment to shrink tumors causing symptoms

Types of radiation therapy:

- External beam radiation therapy (EBRT): Most common; machine directs radiation precisely at affected lymph nodes.

- Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): More precise shaping of the radiation beam to spare healthy tissue.

- Proton therapy: Less common but reduces radiation to surrounding organs.

Side effects:

- Skin redness and irritation

- Fatigue

- Temporary hair loss in the treated area

- Risk of secondary cancers or heart/lung damage years later (especially if the mediastinum is irradiated)

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapies focus on specific molecules or pathways involved in lymphoma cell growth and survival. They spare more normal cells than traditional chemotherapy.

Examples:

Monoclonal antibodies:

Rituximab: Targets CD20 on B cells; revolutionized treatment for many B-cell lymphomas.

Obinutuzumab: Another anti-CD20 antibody, sometimes used in rituximab-resistant cases.

Brentuximab vedotin: Antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD30, used in HL and ALCL.

Small molecule inhibitors:

BTK inhibitors (e.g., ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib): Block B-cell receptor signaling; used in mantle cell lymphoma, CLL/SLL.

PI3K inhibitors (e.g., idelalisib, copanlisib): Interfere with pathways that help cancer cells survive.

BCL-2 inhibitors (e.g., venetoclax): Induce apoptosis in lymphoma cells.

Advantages:

- Often effective in resistant disease

- May be taken orally in pill form

- Can be combined with chemotherapy (chemoimmunotherapy)

Challenges:

- Can still cause significant side effects (infusion reactions, infections, cardiac effects)

- Resistance can develop over time

Immunotherapy

Harnesses the body’s immune system to attack cancer.

Approaches:

Checkpoint inhibitors:

Drugs like nivolumab and pembrolizumab block PD-1, a checkpoint protein that suppresses immune responses. Useful in relapsed/refractory HL.

CAR T-cell therapy:

Patient’s own T cells are collected, genetically modified to recognize lymphoma cells, and reinfused.

Effective in certain aggressive B-cell lymphomas that don’t respond to other treatments.

Potential for long-term remission after a single infusion.

Bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs):

Molecules like mosunetuzumab that bind both T cells and lymphoma cells, bringing them into contact for killing.

Potential risks:

- Cytokine release syndrome (CRS): Can cause fever, low blood pressure, organ dysfunction.

- Neurological side effects (confusion, seizures in rare cases).

- Requires specialized treatment centers.

Stem Cell Transplantation

Used mainly for relapsed or high-risk disease.

Two types:

Autologous transplant (auto-SCT):

Patient’s own stem cells are collected before high-dose chemotherapy.

High-dose chemo wipes out both lymphoma and bone marrow.

Stem cells are reinfused to restore blood cell production.

Allogeneic transplant (allo-SCT):

Stem cells come from a matched donor.

Donor immune system can attack residual cancer cells (graft-versus-lymphoma effect).

Higher risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Main challenges:

- High risk of infections and complications.

- Requires good overall health and close monitoring.

Watchful Waiting (Active Surveillance)

For slow-growing lymphomas like follicular lymphoma or small lymphocytic lymphoma, immediate treatment is not always necessary.

Why it’s done:

- Early treatment hasn’t been shown to improve long-term survival for indolent types without symptoms.

- Avoids side effects of therapy for as long as possible.

Monitoring involves:

- Regular physical exams

- Blood tests

- Imaging as needed

Treatment begins when there are symptoms or clear signs of progression (e.g., rapid node growth, B symptoms, organ compromise).

Combination Strategies

Many treatment plans involve sequential or concurrent combinations:

- Chemoimmunotherapy: Combining chemotherapy with rituximab (e.g., R-CHOP).

- Radiotherapy + chemotherapy for early HL.

- Targeted therapy + immunotherapy in relapsed cases.

Supportive and Palliative Care

Regardless of treatment stage, supportive care is critical:

- Infection prevention: Vaccinations, prophylactic antibiotics.

- Managing anemia: Iron, erythropoietin-stimulating agents, or transfusions.

- Pain control: Medications, nerve blocks.

- Nutrition and exercise programs to maintain strength.

- Psychosocial support for patients and families.

Prognosis

Prognosis varies widely:

- HL: 5-year survival rates > 85% for early stages.

- Aggressive NHL (e.g., DLBCL): 5-year survival ~ 60–70% with modern therapy.

- Indolent NHL: Long survival possible, but often considered incurable; may transform into aggressive form.

Prognostic tools like the International Prognostic Index (IPI) help guide treatment.

Advances in Research

Recent years have brought major breakthroughs:

- Next-generation sequencing for precise genetic profiling.

- Novel targeted drugs such as BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib) for mantle cell lymphoma.

- Expansion of bispecific antibodies that engage T cells to attack lymphoma cells.

- Improved CAR T-cell designs for longer-lasting remissions.

Living with Lymphoma

Beyond medical treatment, patients face emotional, psychological, and practical challenges:

- Supportive care for managing fatigue, infections, and side effects.

- Nutritional guidance to maintain strength during therapy.

- Psychological counseling for anxiety, depression, or fear of recurrence.

- Survivorship programs that address long-term health monitoring.

Conclusion

Lymphoma is not a single disease but a family of related cancers with highly variable behaviors, outcomes, and treatments. Advances in diagnosis, molecular biology, and targeted therapy have transformed the outlook for many patients—turning once-fatal conditions into manageable or even curable diseases.

Ongoing research promises even more individualized and effective approaches in the years ahead. For patients, timely diagnosis, access to specialized care, and comprehensive support systems remain the key to the best possible outcomes.