Examination of the oral cavity is a cornerstone of dental and medical practice. It not only enables the clinician to diagnose obvious dental disease such as caries and periodontal problems but also provides critical information about systemic health, habits, and risk factors. The mouth is often described as a mirror of the body; early signs of nutritional deficiencies, systemic infections, and autoimmune or malignant conditions can manifest in the oral tissues long before they appear elsewhere.

While most dental textbooks describe a detailed and exhaustive process for oral examination, in real-world clinical settings, practitioners must balance thoroughness with efficiency. Patients may present in pain, or time constraints in busy clinics may not allow lengthy assessments. Therefore, developing a systematic, reproducible approach is vital. This ensures that no important detail is missed, whether the patient is asymptomatic, attending for routine care, or presenting with complex problems.

Table of Contents

ToggleIntra-Oral Examination

The intra-oral examination provides direct information about the teeth, soft tissues, periodontal structures, and occlusion.

Oral hygiene assessment

Evaluating plaque and calculus accumulation is essential. Rather than subjective scoring (“good” or “poor”), validated plaque indices provide objective benchmarks. For example, the Plaque Control Record or Silness-Löe Index. Higher scores allow clinicians to motivate patients by showing measurable improvement over time.

Soft tissue inspection

All mucosal surfaces must be inspected systematically: lips, buccal mucosa, gingiva, palate, tongue, and floor of mouth.

- Ulcers: Any ulcer persisting for more than three weeks requires urgent investigation, as this could signal malignancy.

- White or red patches: Leukoplakia or erythroplakia may indicate precancerous lesions.

- Vesicles or erosions: May suggest viral infections (e.g., herpes simplex), autoimmune conditions (pemphigus, lichen planus), or allergic reactions.

The tongue deserves particular attention. Restricted mobility, masses, or induration can be early signs of carcinoma. Lateral tongue borders and floor of mouth are especially high-risk areas.

Periodontal assessment

Using a periodontal probe, clinicians quickly assess pocket depths, bleeding, and attachment loss. The Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) is often used as a screening tool, providing a score that dictates whether further, more detailed charting is required.

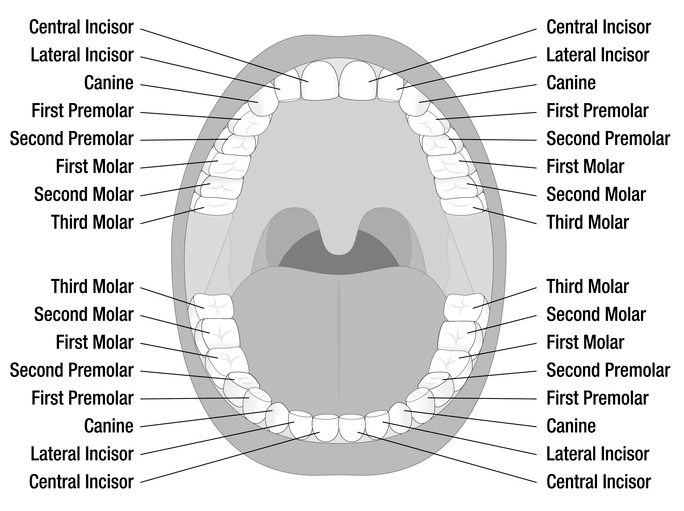

Charting and tooth notation

Recording present teeth and missing ones is fundamental. Caries, restorations, wear, fractures, and anomalies must be documented systematically. Various systems exist for tooth notation (see section below). Accurate records are crucial for medico legal purposes, treatment planning, and communication with colleagues.

Caries detection

Caries should be detected by a combination of visual inspection, probing (carefully, to avoid cavitation of incipient lesions), and radiographs when indicated. Recording the site, size, and activity of lesions helps in planning preventive or restorative strategies.

Restorations

Existing restorations are examined for integrity, marginal adaptation, secondary caries, and occlusal relationships. Poor restorations may cause food packing, caries, or periodontal issues.

Occlusion

Occlusal analysis involves assessing how upper and lower teeth meet when the mouth is closed.

- Static occlusion: Evaluates intercuspation, overbite, overjet, and crossbites.

- Dynamic occlusion: Considers contacts during lateral and protrusive movements.

Malocclusion may cause trauma, mobility, or temporomandibular problems.

Tooth wear

Attrition, abrasion, erosion, and abfraction are forms of tooth surface loss. Their identification helps in preventive and restorative care. Erosion from dietary acids, attrition from bruxism, and abrasion from incorrect brushing techniques are common causes.

Clinical example

A 22-year-old student presents for a check-up. IO examination reveals generalized erosive tooth surface loss, particularly on palatal surfaces of maxillary incisors. On further questioning, the patient admits to frequent vomiting due to an eating disorder. This highlights how IO examination can reveal systemic or psychological conditions.

Investigations

Where clinical examination suggests pathology, investigations may be required. These include:

- Radiographs (bitewings, periapicals, panoramic, CBCT)

- Microbiological tests (swabs, smears)

- Blood tests (e.g., for suspected anemia, diabetes)

- Biopsies of suspicious lesions

Special investigations should be guided by the findings of the systematic examination.

Tooth Notation Systems

Recording dental findings requires a clear, universally understood method of tooth identification. Several systems exist, each with its advantages.

1. FDI World Dental Federation (ISO system)

The FDI system is internationally recognized and widely used. Each tooth is assigned a two-digit number:

- First digit = quadrant (1 to 4 for permanent teeth, 5 to 8 for deciduous teeth).

- Second digit = tooth position from the midline (1 to 8 permanent, 1 to 5 deciduous).

Example:

- UR1 (upper right central incisor) = 11

- LL7 (lower left second molar) = 37

- UR second deciduous molar = 55

Advantages: simple, computer-friendly, and universally accepted.

Disadvantages: Numbers may be confusing without quadrant context.

2. Zsigmondy–Palmer / Chevron / Set-square system

Introduced in the 19th century, this system uses a cross-shaped grid to denote quadrants. Numbers (1–8) are placed within the quadrant to indicate tooth position. For deciduous teeth, letters (a–e) are used.

Example:

- Upper right central incisor = ┘1

- Lower left second molar = ┌7

Advantages: Easy visualization of quadrants.

Disadvantages: Difficult to reproduce in typed text.

3. European system

Sometimes called the “plus-minus system.” Permanent teeth are numbered from the midline outwards (1–8) with plus or minus signs to denote upper/lower and right/left. Deciduous teeth use 01–05.

Example:

- Upper right central incisor = +1

- Lower left canine = –3

Advantages: Logical numbering sequence.

Disadvantages: Not widely used outside Europe; symbols difficult in digital documents.

4. American (Universal) system

Teeth are numbered consecutively from 1 to 32, starting from the upper right third molar and moving clockwise. Deciduous teeth are assigned letters A–T.

Example:

- Upper right third molar = #1

- Lower left central incisor = #24

- Primary upper right second molar = A

Advantages: Very straightforward once memorized.

Disadvantages: Not easily intuitive; lacks quadrant logic.

Comparative Use and Clinical Importance

Different countries favor different systems.

- Europe, Asia, Africa: predominantly FDI.

- USA: Universal (American) system is dominant.

- UK: Palmer notation still common in orthodontics.

In clinical practice, consistency is crucial. Using the wrong system can cause serious errors. For instance, extracting “tooth 37” under FDI refers to the lower left second molar, whereas in the American system tooth #37 does not exist!

Medico-Legal and Communication Aspects

Accurate notation is not just academic; it has practical implications:

- Treatment planning: Wrong notation may lead to treatment of the wrong tooth.

- Referral letters: Clear communication prevents misunderstandings between practitioners.

- Forensic dentistry: Dental records are often used to identify individuals in disaster victim identification.

- Legal accountability: Inaccurate or unclear notes can expose clinicians to litigation.

Digital and Modern Developments

Electronic dental records (EDR) increasingly incorporate graphical tooth charts. These allow clinicians to click on a tooth and record findings digitally, often using FDI notation. Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools are also being developed to automatically chart caries, restorations, and missing teeth from radiographs.

Conclusion

The systematic examination of the mouth, beginning with extra-oral assessment and moving to detailed intra-oral evaluation, is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Tooth notation systems provide the framework for recording and communicating findings. While multiple systems exist, understanding their history, logic, and regional use ensures clarity and avoids errors.

Ultimately, a thorough, structured approach protects both patient and practitioner, ensuring that nothing is overlooked and that dental records remain clear, defensible, and useful for ongoing care.

References

- Walsh, T. F., & Glenwright, H. D. (2013). Oxford Handbook of Clinical Dentistry (6th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bartold, P. M., & Van Dyke, T. E. (2013). Periodontitis: A host-mediated disruption of microbial homeostasis. Periodontology 2000, 62(1), 203–217.

- World Dental Federation (FDI). (2020). FDI Tooth Numbering System.

- British Dental Association (BDA). (2021). Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE): Guidance Notes.

- Laskin, D. M. (2015). Textbook of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (2nd ed.). Mosby Elsevier.

- Langlais, R. P., Miller, C. S., & Gehrig, J. S. (2017). Color Atlas of Common Oral Diseases (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

- Carranza, F. A., & Newman, M. G. (2018). Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology (13th ed.). Elsevier.

- American Dental Association (ADA). (2018). Universal Numbering System (Tooth Number Chart).

- Peck, S. (2016). Tooth numbering systems and their evolution. International Dental Journal, 66(2), 71–78.

- Greenberg, M. S., Glick, M., & Ship, J. A. (2019). Burket’s Oral Medicine (13th ed.). PMPH USA.