Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures. It affects people of all ages, backgrounds, and walks of life. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 50 million people worldwide live with epilepsy, making it one of the most common neurological conditions globally. Despite its prevalence, epilepsy is often misunderstood, stigmatized, and surrounded by myths. This article delves deep into the nature of epilepsy, exploring its causes, types, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment options, and strategies for living with the condition.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is Epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a chronic disorder of the brain marked by a persistent predisposition to generate epileptic seizures. It is a clinical condition that manifests with at least two unprovoked seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart. The disorder results from excessive and abnormal neuronal activity in the brain, which may produce a wide range of symptoms depending on the part of the brain affected.

A seizure occurs when there is a sudden, uncontrolled electrical disturbance in the brain. This disruption can lead to changes in behavior, movements, feelings, and levels of consciousness. While seizures are the key feature of epilepsy, it is important to note that not all seizures signify epilepsy. Isolated seizures, particularly those triggered by identifiable causes such as fever, trauma, or alcohol withdrawal, do not usually indicate an epileptic condition.

Epilepsy is not a singular disease but rather a spectrum of disorders that encompass a wide variety of seizure types and control difficulties. It may affect only one part of the brain (focal epilepsy) or involve both hemispheres (generalized epilepsy). Furthermore, epilepsy can vary significantly between individuals, in terms of seizure frequency, severity, underlying cause, and response to treatment.

The condition can develop at any age, but it most commonly begins in childhood or after the age of 60. The impact of epilepsy extends beyond seizures, affecting emotional well-being, cognitive function, and quality of life. Many individuals with epilepsy lead full, active lives with proper management and support, but for others, the condition can present substantial challenges.

The underlying causes of epilepsy are often diverse. In some people, the condition is due to genetic mutations that alter brain function. In others, epilepsy arises from brain injuries, infections, tumors, or structural abnormalities. Despite extensive testing, the cause remains unknown in about 50% of cases, often referred to as idiopathic epilepsy.

Accurate diagnosis and classification of epilepsy are critical for choosing the most effective treatment strategy. With advances in neuroimaging, genetics, and pharmacology, many individuals with epilepsy are able to achieve complete seizure control or significantly reduce their seizure frequency.

Understanding the nature of epilepsy is the first step toward effective management, improved public awareness, and a reduction in the stigma that often surrounds this condition. It is a medical disorder that, with the right approach, can be controlled to allow individuals to live fulfilling and productive lives.

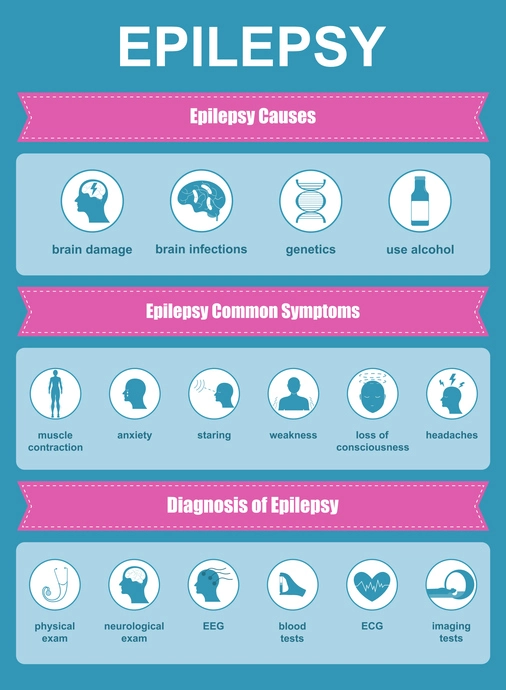

Causes of Epilepsy

The causes of epilepsy are varied and multifactorial, encompassing genetic, structural, metabolic, immune, and infectious origins. Understanding these diverse causes is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. They can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Genetic Influence

- Structural Causes

- Head Trauma

- Brain Conditions

- Infectious Diseases

- Prenatal and Perinatal Injury

- Metabolic Disorders

- Immune Disorders

- Unknown or Idiopathic Causes

Genetic Influence

A number of epilepsy syndromes are known to have a genetic basis. Some forms of epilepsy are inherited, while others result from spontaneous genetic mutations. Genes can influence brain cell development and function, and mutations in these genes may make neurons more excitable and prone to abnormal firing. Genetic epilepsies are often seen in childhood and may respond well to specific treatments.

Structural Causes

Abnormalities in brain structure, whether congenital (present at birth) or acquired, can lead to epilepsy. These structural abnormalities might include cortical dysplasia (disorganized brain cell development), tumors, vascular malformations, or scarring from traumatic injuries. Structural causes are often identifiable through neuroimaging techniques like MRI and may be amenable to surgical intervention in drug-resistant cases.

Head Trauma

A significant head injury—such as from a car accident, sports injury, or fall—can damage brain tissue and lead to post-traumatic epilepsy. Seizures may not occur immediately but can develop months or even years later. Prompt treatment and protective headgear in high-risk activities can help reduce this risk.

Brain Conditions

Conditions that affect brain function, such as strokes, brain tumors, or neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease), are recognized causes of epilepsy. Stroke is the leading cause of new-onset epilepsy in older adults, largely due to the damage it inflicts on brain tissue and blood flow.

Infectious Diseases

Certain infections can affect the brain and central nervous system, leading to inflammation and seizures. These include meningitis, encephalitis, HIV/AIDS, and parasitic infections such as neurocysticercosis, which is caused by the pork tapeworm. Timely treatment of infections and vaccination can reduce epilepsy risk from infectious causes.

Prenatal and Perinatal Injury

Epilepsy can develop due to brain injuries that occur before or during birth. Factors include oxygen deprivation, maternal infections, prolonged labor, or birth trauma. These injuries can disrupt normal brain development and increase the likelihood of seizures later in life.

Metabolic Disorders

Disorders that disrupt the body’s metabolism—such as low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), electrolyte imbalances, or rare inherited metabolic diseases—can provoke seizures. In some cases, identifying and treating the metabolic issue can eliminate or significantly reduce seizure activity.

Immune Disorders

Autoimmune conditions where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy brain tissue can lead to inflammation and seizures. Autoimmune epilepsy is an emerging field of research and may respond to immunotherapy in addition to standard anti-epileptic drugs.

Unknown or Idiopathic Causes

In nearly half of all epilepsy cases, no specific cause can be identified despite thorough evaluation. These are termed idiopathic or cryptogenic epilepsy. Even in the absence of a known cause, many people with idiopathic epilepsy respond well to treatment and lead seizure-free lives.

Recognizing the underlying cause of epilepsy is crucial for tailoring treatment and determining prognosis. As medical research advances, our understanding of epilepsy’s origins continues to grow, offering hope for more personalized and effective therapies.

Types of Seizures

Seizures are broadly classified into two main categories: focal (partial) seizures and generalized seizures. However, there are also seizures that do not fit neatly into these categories and are referred to as unknown onset or unclassified seizures. Understanding the various types is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Focal Seizures (Partial Seizures)

These originate in a specific area of the brain and can affect awareness to varying degrees.

- Focal Aware Seizures (formerly simple partial seizures): In this type, the person is fully conscious and aware during the seizure. Symptoms might include unusual sensations, such as tingling, flashing lights, or changes in smell or taste. They may also involve sudden emotional changes like fear or joy.

- Focal Impaired Awareness Seizures (formerly complex partial seizures): These seizures alter awareness or responsiveness. The individual may appear to stare blankly, not respond to questions or commands, and engage in automatic behaviors like hand rubbing, chewing, or walking in circles. Memory of the event may be impaired.

- Focal to Bilateral Tonic-Clonic Seizures: A seizure that starts in one part of the brain and then spreads to both hemispheres, resulting in a generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

Generalized Seizures

These affect both hemispheres of the brain from the onset and often result in loss of consciousness. Types include:

- Absence Seizures (petit mal): Characterized by brief staring spells that last a few seconds. These are common in children and may occur multiple times a day. The person may not be aware they had a seizure.

- Tonic Seizures: Involve sudden muscle stiffening, often affecting the back, arms, and legs. These seizures can cause falls due to loss of postural control.

- Atonic Seizures (drop attacks): Involve a sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to the individual collapsing or dropping their head. These seizures carry a high risk of injury.

- Clonic Seizures: Involve rhythmic, jerking muscle movements, typically affecting the arms, neck, and face.

- Myoclonic Seizures: Sudden, brief jerks or twitches of a muscle or group of muscles. They often occur shortly after waking up and can be mistaken for normal muscle twitches.

- Tonic-Clonic Seizures (grand mal): The most dramatic type of seizure, featuring a combination of tonic and clonic phases. The person may cry out, fall to the ground, convulse, and lose consciousness. It may also involve loss of bladder or bowel control and tongue biting.

Unknown Onset Seizures

When the beginning of a seizure is not observed or is unclear, it is classified as unknown onset. Over time, as more information is gathered, these seizures may be reclassified as focal or generalized.

Non-Epileptic Seizures

These resemble epileptic seizures but are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. They may be related to psychological conditions or physical issues like fainting. A thorough diagnosis, including EEG and video monitoring, is essential to distinguish between the two.

Each seizure type can vary widely in presentation and duration. Some people may experience only one type of seizure, while others may have multiple types. Understanding the exact seizure type helps healthcare providers tailor the most effective treatment and management strategies.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

The primary symptom of epilepsy is the occurrence of seizures. However, epilepsy can manifest with a broad spectrum of symptoms depending on the type of seizure and the part of the brain affected. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Temporary confusion

- Staring spells

- Uncontrollable jerking movements of the arms and legs

- Loss of consciousness or awareness

- Sudden feelings of fear, anxiety, or déjà vu

- Unusual sensations affecting vision, hearing, or smell

- Repetitive movements like lip smacking, fidgeting, or hand wringing

Some individuals may experience an aura—a warning sensation that precedes a seizure. Auras can present as a particular smell, taste, or visual disturbance, and are often considered a type of focal aware seizure.

Diagnosing epilepsy requires a careful and comprehensive evaluation. This typically involves:

- Detailed Medical History: A full account of the seizure episodes, including when they occur, what happens before and during the seizure, duration, and recovery, as well as family history and other medical conditions.

- Neurological Examination: Assessment of motor skills, reflexes, coordination, mental status, and sensory function to identify potential neurological causes.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG): The gold standard for epilepsy diagnosis. EEG measures electrical activity in the brain and can reveal patterns that indicate a predisposition to seizures, even between episodes.

- Imaging Studies: MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and CT (Computed Tomography) scans help detect structural abnormalities, such as tumors, scar tissue, or brain malformations, that may be causing seizures.

- Blood Tests: To identify metabolic or infectious conditions that could be contributing to seizures, such as electrolyte imbalances or infections.

- Video EEG Monitoring: In cases where diagnosis is uncertain, patients may be monitored in a hospital setting with continuous EEG and video recording to capture seizure activity for detailed analysis.

An accurate diagnosis not only confirms the presence of epilepsy but also helps classify the seizure type and identify potential underlying causes. This information is crucial for selecting the most effective treatment plan and improving long-term outcomes.

Treatment Options

Epilepsy can often be managed effectively with a combination of treatments tailored to the individual’s seizure type, frequency, cause, and lifestyle. The primary goals are to control seizures, minimize side effects, and improve quality of life. Common treatment approaches include:

- Medication

- Surgical Interventions

- Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

- Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS)

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

- Dietary Therapies

- Complementary and Alternative Therapies

- Lifestyle Modifications and Support

Medication

Anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) are the first line of treatment for most people with epilepsy. These drugs stabilize electrical activity in the brain and can successfully control seizures in about 70% of patients. There are many types of AEDs available, including older medications like phenytoin and valproate, and newer ones like levetiracetam and lamotrigine. The choice of medication depends on factors such as seizure type, age, sex, lifestyle, and co-existing medical conditions. Dosing needs to be carefully monitored, and side effects such as fatigue, dizziness, mood changes, or weight fluctuations must be managed.

Surgical Interventions

For people who do not respond adequately to medication (known as drug-resistant or refractory epilepsy), surgery may be a viable option. Surgical procedures aim to remove or alter the brain area responsible for seizures. Common surgeries include:

- Lobectomy: Removal of the affected lobe (e.g., temporal lobectomy)

- Lesionectomy: Removal of specific lesions or tumors

- Corpus Callosotomy: Cutting the corpus callosum to reduce seizure spread

- Hemispherectomy: Removal or disconnection of one cerebral hemisphere (used in extreme cases) Surgery is usually considered after extensive testing, including video EEG and brain imaging, to precisely locate the seizure focus.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

VNS involves the surgical implantation of a device under the skin in the chest. The device sends regular electrical impulses to the brain via the vagus nerve in the neck. It does not stop seizures entirely but can reduce their frequency and severity. It is often used in individuals who are not candidates for brain surgery or whose seizures are not fully controlled by medication alone.

Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS)

RNS is an advanced treatment involving a neurostimulator implanted in the skull, which is connected to electrodes placed at the seizure onset zone in the brain. The device monitors brain activity in real-time and delivers electrical stimulation when it detects abnormal activity, aiming to prevent seizures before they occur.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

Similar to RNS, DBS involves implanting electrodes into specific deep brain structures (such as the thalamus) that are involved in seizure regulation. A pulse generator sends electrical signals to modulate abnormal brain activity. DBS is used for adults with treatment-resistant epilepsy.

Dietary Therapies

Special diets can help some people with epilepsy, especially children with refractory seizures. The most well-known is the Ketogenic Diet, which is high in fats and low in carbohydrates. It shifts the body’s metabolism to ketosis, which has been shown to reduce seizure activity. Other diet variations include the Modified Atkins Diet and the Low Glycemic Index Treatment (LGIT).

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Some individuals explore complementary therapies such as yoga, acupuncture, meditation, or herbal supplements to manage stress and improve well-being. While these approaches may support overall health, they should not replace conventional medical treatments. Always consult a healthcare provider before using alternative therapies.

Lifestyle Modifications and Support

Lifestyle factors can influence seizure control. Adequate sleep, stress management, avoiding alcohol and recreational drugs, and adherence to prescribed treatment plans are essential. Regular medical follow-ups, seizure tracking, and psychological support contribute significantly to long-term seizure control and emotional well-being.

Because epilepsy is a chronic condition, treatment is often long-term and may require periodic adjustments. A multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists, dietitians, psychologists, and support groups is often the most effective strategy for managing the condition comprehensively.

Living with Epilepsy

Living with epilepsy requires a multifaceted approach that goes beyond medical treatment. Individuals must learn to navigate everyday challenges, manage emotional well-being, and adapt their lifestyle to maintain safety and independence. Support from healthcare professionals, family, employers, and social communities plays a critical role in improving the overall quality of life.

Education and Employment

Many people with epilepsy pursue education and employment successfully. Open communication with teachers and employers can help create an accommodating environment. Some may need reasonable adjustments such as flexible schedules or breaks for medical needs. Career choices may be influenced by seizure control, with certain high-risk jobs (e.g., operating heavy machinery, flying aircraft) being restricted, but with proper management, most fields remain accessible.

Driving and Transportation

Driving laws vary by country and typically require individuals to be seizure-free for a specified duration (e.g., 6 to 12 months). Regular check-ups and compliance with treatment are crucial to retaining driving privileges. For those who cannot drive, access to public transport or community mobility services becomes essential for independence.

Mental Health and Emotional Well-being

Depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem are more common among people with epilepsy, particularly if the condition is uncontrolled or unpredictable. Therapy, support groups, and psychiatric care can help individuals process the emotional effects of living with a chronic condition. Mindfulness practices and stress-reduction techniques may also reduce seizure frequency in some individuals.

Relationships and Social Life

Epilepsy can affect social interactions and relationships. Fear of having a seizure in public may cause isolation. It is important to educate friends and loved ones about the condition and how to respond during a seizure. Building a network of understanding individuals can foster confidence and connection.

Lifestyle and Safety Measures

Safety considerations are important for people with epilepsy, especially when engaging in activities like swimming, climbing, or cooking. Strategies to enhance safety include:

- Taking showers instead of baths

- Avoiding heights without supervision

- Using guards or automatic shut-offs for cooking equipment

- Wearing medical alert jewelry

Women and Epilepsy

Women with epilepsy may face unique challenges related to menstruation, contraception, pregnancy, and menopause. Hormonal changes can affect seizure patterns, and some anti-epileptic medications may interact with birth control or pose risks during pregnancy. Preconception counseling and collaboration with neurologists and obstetricians are essential for managing reproductive health.

Children and Adolescents

For children, epilepsy can impact academic performance, self-image, and social development. Schools should be informed and prepared to support a child with epilepsy through Individualized Education Plans (IEPs), emergency protocols, and inclusive practices. Adolescents may require additional support as they gain independence and transition to adult care.

Aging and Epilepsy

Older adults with epilepsy may experience cognitive decline, medication sensitivity, and higher fall risk. Regular medication reviews and fall-prevention strategies are essential in this population. Caregivers play a vital role in assisting with medication adherence and recognizing changes in seizure patterns.

Advocacy and Community Support

Engaging with epilepsy organizations and advocacy groups can provide access to educational resources, peer support, and public awareness campaigns. Community involvement reduces stigma, encourages research, and empowers individuals to advocate for better care and inclusive policies.

Technology and Seizure Monitoring

Technology is increasingly helpful for people living with epilepsy. Seizure-tracking apps, wearable monitors, and automated alert systems can improve safety and aid healthcare providers in monitoring treatment effectiveness. Remote consultations and telehealth also enhance access to specialists.

Myths and Misconceptions

There are many myths about epilepsy that contribute to stigma and misunderstanding:

Myth: Epilepsy is contagious.

Fact: Epilepsy is not contagious.

Myth: People with epilepsy are mentally ill.

Fact: Epilepsy is a neurological condition, not a mental illness.

Myth: You should put something in the mouth of someone having a seizure.

Fact: Never put anything in a person’s mouth during a seizure.

First Aid for Seizures

Knowing how to respond to a seizure can save lives and reduce the risk of injury. While most seizures are not medical emergencies, proper first aid can make a significant difference in the outcome. Here are detailed steps to follow:

1. Stay Calm and Stay with the Person: Remain as calm as possible. Your presence is reassuring, and staying nearby allows you to monitor the seizure and provide help if needed.

2. Time the Seizure: Use a watch or phone to measure the length of the seizure. If it lasts more than 5 minutes, call emergency services immediately, as prolonged seizures (status epilepticus) require urgent medical attention.

3. Protect from Injury: Clear the area around the person of any sharp or dangerous objects. Cushion their head with something soft like a jacket or pillow, and loosen any tight clothing around the neck to aid breathing.

4. Do Not Restrain Them: Never try to hold the person down or stop their movements. Let the seizure run its course while ensuring their safety.

5. Do Not Put Anything in Their Mouth: Contrary to common myths, never place objects (including fingers) in the person’s mouth. This can cause choking or injury. It’s impossible for someone to swallow their tongue during a seizure.

6. Turn Them on Their Side: If possible, gently roll the person onto one side to keep the airway clear and prevent choking on saliva or vomit.

7. Stay with Them Until Fully Alert: After the seizure, the person may be confused, tired, or disoriented. Stay with them, offer reassurance, and help them recover. Let them rest and avoid offering food or drink until they are fully alert.

8. Offer Help Afterward: Some people may be embarrassed or emotional post-seizure. Provide comfort and ask if they would like assistance contacting someone or getting to a safe place.

9. When to Call for Emergency Help:

- If the seizure lasts longer than 5 minutes

- If another seizure follows immediately

- If the person is injured during the seizure

- If the person has difficulty breathing or waking afterward

- If the seizure occurs in water

- If it’s the person’s first known seizure

- If the person is pregnant, diabetic, or has another medical condition

10. Seizures in Children: Children with epilepsy may have different needs. Communicate with parents or guardians about existing care plans. For febrile seizures (caused by fever), seek medical advice to determine if further evaluation is needed.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main cause of epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurring, unprovoked seizures. The causes of epilepsy can vary widely. Some common causes include brain injuries (such as trauma from accidents), genetic conditions, brain infections (like meningitis or encephalitis), stroke, brain tumors, or developmental disorders. In many cases, however, especially among adults and older individuals, no identifiable cause is found—this is referred to as idiopathic epilepsy.

What should a person with epilepsy avoid?

People with epilepsy should try to avoid known seizure triggers, which can vary by individual. Common things to avoid include:

- Sleep deprivation – lack of sleep can increase seizure risk.

- Stress – emotional stress and anxiety can be major triggers.

- Flashing or flickering lights – particularly for those with photosensitive epilepsy.

- Alcohol and recreational drugs – these can interfere with seizure control and medications.

- Missing medication doses – skipping or stopping anti-epileptic drugs can trigger seizures.

- Extreme physical exertion or overheating – can sometimes provoke seizures in sensitive individuals.

What is it like having epilepsy?

Living with epilepsy can be very different from one person to another. Some may experience frequent and severe seizures, while others may go months or years between seizures. People with epilepsy often have to manage the unpredictability of seizures, deal with the side effects of medications, and cope with stigma or social misunderstandings. It can also affect driving privileges, employment opportunities, and independence. However, with the right support, treatment, and lifestyle adjustments, many people with epilepsy lead happy and successful lives.

Can a person with epilepsy live a normal life?

Yes, many people with epilepsy live completely normal, fulfilling lives. While there may be some limitations or adjustments required—such as taking medication regularly, avoiding specific triggers, or following medical guidance—most individuals with epilepsy can work, go to school, have relationships, and pursue hobbies just like anyone else. Advances in treatment and better understanding of epilepsy have greatly improved the quality of life for those affected.

Can epilepsy go away?

In some cases, epilepsy can go into remission, meaning a person stops having seizures for a long period—sometimes permanently. Children may outgrow certain types of epilepsy as they mature. Others may experience remission after successful treatment or surgery. However, epilepsy is often a long-term condition and requires ongoing management. The likelihood of epilepsy “going away” depends on the type, cause, and response to treatment.

Is epilepsy a disability?

Yes, epilepsy is considered a neurological disability. Depending on the severity and frequency of seizures, it may qualify as a disability under medical and legal definitions in many countries. This means individuals with epilepsy may be entitled to certain protections, accommodations, and support—such as modified work environments, disability benefits, or special considerations at school or work. However, many people with epilepsy do not see themselves as disabled and live fully independent lives.

What will trigger epilepsy?

Seizure triggers differ between individuals, but common ones include:

- Lack of sleep

- Emotional stress or anxiety

- Flashing lights or visual patterns (especially for photosensitive epilepsy)

- Alcohol or drug use

- Skipping meals or low blood sugar

- Illnesses with fever

- Hormonal changes, such as during menstruation Identifying and avoiding personal triggers is a key part of epilepsy management.

Does epilepsy get worse with age?

Epilepsy does not always get worse with age, but in some cases, it can change over time. Some people experience fewer seizures as they age, while others may develop more frequent or severe seizures due to age-related changes in the brain or other health conditions. Additionally, older adults are at higher risk of developing epilepsy due to strokes, brain tumors, or neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. Regular medical follow-up is important to adjust treatment as needed.

What is forbidden in epilepsy?

While nothing is strictly “forbidden” across the board, people with epilepsy are advised to avoid certain activities that could be dangerous during a seizure. These may include:

- Driving (unless medically cleared and seizure-free for a certain period)

- Operating heavy machinery

- Swimming or bathing alone

- Working at heights or near open flames

- Contact sports without safety measures These restrictions help reduce the risk of injury and are often determined by local laws and doctors’ recommendations.

Are you born with epilepsy or does it develop?

Epilepsy can be either congenital (present at birth) or acquired later in life. Some people are born with a genetic tendency toward epilepsy or brain abnormalities that lead to seizures early in life. Others may develop epilepsy due to brain injury, infections, tumors, or other neurological conditions that appear later. It can also develop with no known cause, at any age.

What are people with epilepsy not allowed to do?

Restrictions vary depending on the type and control of seizures. Generally, people with epilepsy may be restricted from:

- Driving, unless they meet legal seizure-free requirements

- Joining certain military or law enforcement roles

- Flying aircraft

- Scuba diving or solo swimming

- Handling dangerous machinery without supervision That said, many people with epilepsy can still participate in a wide range of activities with proper support and precautions.

What can calm epilepsy?

Epilepsy can be managed and sometimes “calmed” through a combination of strategies:

- Anti-seizure medications – the primary treatment option.

- Stress reduction techniques – like mindfulness, meditation, or therapy.

- Regular sleep schedules – to avoid sleep deprivation.

- Healthy diet and hydration

- Avoiding known triggers – based on personal experience.

- Ketogenic diet – in some cases, particularly for drug-resistant epilepsy.

- Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) or epilepsy surgery – for severe, treatment-resistant cases. Working closely with a neurologist is key to finding the right combination of treatments.