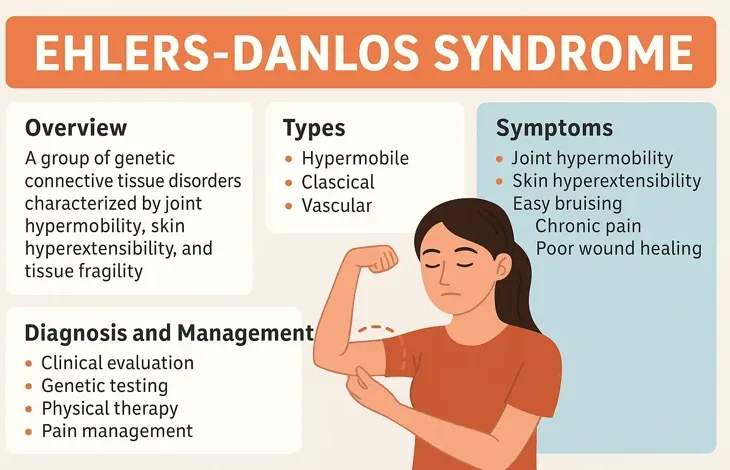

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) is a group of rare, heritable connective tissue disorders characterized by joint hypermobility, skin hyperextensibility, and tissue fragility. It is named after two physicians—Edvard Ehlers, a Danish dermatologist, and Henri-Alexandre Danlos, a French physician—who first described its manifestations in the early 20th century. Since then, advances in genetics and clinical medicine have significantly expanded the medical community’s understanding of EDS.

Although often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, EDS affects people worldwide and can range from mild to life-threatening in severity. Its complexity arises from the fact that connective tissue is ubiquitous in the human body—present in skin, blood vessels, ligaments, internal organs, and more. As a result, the symptoms of EDS are diverse and can impact multiple organ systems simultaneously.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat Is Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome?

EDS refers to a group of genetic disorders affecting connective tissue, particularly collagen and related proteins. Collagen is the most abundant protein in the human body and plays a vital role in providing strength, elasticity, and structural integrity to tissues. In EDS, defects in collagen or collagen-related molecules result in weakened connective tissue, leading to hallmark symptoms like hypermobile joints and fragile skin.

The 2017 International Classification of the Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes recognizes 13 subtypes, each associated with specific genetic mutations and clinical features. Some subtypes are relatively benign, while others, such as vascular EDS, pose significant risks due to life-threatening vascular complications.

Types of EDS

1. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS)

- The most common form.

- Characterized by generalized joint hypermobility, chronic joint pain, frequent dislocations, and soft, stretchy skin.

- Unlike most other subtypes, hEDS does not yet have a clearly identified genetic marker, though research suggests an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

2. Classical Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (cEDS)

- Caused by mutations in the COL5A1 or COL5A2 genes.

- Features: highly elastic, velvety skin prone to bruising and scarring, widened atrophic scars, and joint hypermobility.

- Often recognized in childhood.

3. Classical-like EDS (clEDS)

- Caused by mutations in the TNXB gene.

- Shares similarities with classical EDS but without atrophic scarring.

4. Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (vEDS)

- Caused by mutations in the COL3A1 gene.

- The most severe and potentially fatal form due to fragility of arteries, intestines, and internal organs.

- Patients often experience arterial ruptures or aneurysms at a young age.

5. Kyphoscoliotic EDS (kEDS)

- Caused by mutations in the PLOD1 or FKBP14 genes.

- Features: severe congenital muscle hypotonia, scoliosis, and eye abnormalities.

- Infants may present with weak muscle tone and delayed motor development.

6. Arthrochalasia EDS (aEDS)

- Caused by mutations in the COL1A1 or COL1A2 genes.

- Associated with extreme joint laxity, congenital hip dislocation, and fragile skin.

7. Dermatosparaxis EDS (dEDS)

- Caused by mutations in the ADAMTS2 gene.

- Marked by very fragile, sagging skin and severe bruising.

8. Brittle Cornea Syndrome (BCS)

- Caused by mutations in ZNF469 or PRDM5.

- Main feature: thinning and fragility of the cornea, leading to a high risk of rupture.

9. Spondylodysplastic EDS (spEDS)

- Caused by mutations in B4GALT7, B3GALT6, or SLC39A13.

- Features: short stature, developmental delays, muscle hypotonia.

10. Musculocontractural EDS (mcEDS)

- Caused by mutations in CHST14 or DERMATAN SULFATE EPIMERASE genes.

- Associated with joint contractures, distinct facial features, and fragile skin.

11. Myopathic EDS (mEDS)

- Caused by mutations in COL12A1.

- Marked by congenital muscle hypotonia and muscle weakness.

12. Periodontal EDS (pEDS)

- Caused by mutations in C1R or C1S genes.

- Characterized by severe early-onset gum disease leading to tooth loss.

13. Cardiac-valvular EDS (cvEDS)

- Caused by mutations in COL1A2.

- Distinct for severe heart valve problems alongside typical EDS features.

Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations

EDS symptoms vary widely depending on subtype, but some common features include:

Joint-related symptoms

- Hypermobile joints with a large range of motion.

- Frequent dislocations and subluxations.

- Chronic musculoskeletal pain.

- Early-onset osteoarthritis.

Skin-related symptoms

- Hyperextensible (stretchy) skin.

- Velvety or doughy skin texture.

- Easy bruising.

- Poor wound healing and atrophic scarring.

Cardiovascular manifestations

- Vascular fragility (especially in vEDS).

- Aneurysms, dissections, or ruptures.

- Mitral valve prolapse or aortic root dilation in some subtypes.

Neurological manifestations

- Headaches, particularly migraines.

- Dysautonomia (including postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, POTS).

- Nerve compression syndromes.

Gastrointestinal issues

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)-like symptoms.

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Hernias, rectal prolapse.

Other manifestations

- Chronic fatigue.

- Fragile corneas or vision problems.

- Dental issues (especially in periodontal EDS).

Causes and Genetics

EDS is primarily caused by mutations in genes responsible for collagen synthesis, structure, and processing. Collagen types I, III, and V are the most commonly affected.

- Autosomal Dominant Inheritance: Seen in many types such as classical, hypermobile, and vascular EDS.

- Autosomal Recessive Inheritance: Observed in rare types like kyphoscoliotic and dermatosparaxis EDS.

In hEDS, the exact genetic cause is not fully understood. Researchers suspect polygenic inheritance or mutations in regulatory regions affecting collagen function.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing EDS can be challenging due to symptom variability and overlap with other conditions. Diagnosis typically involves:

1. Clinical Evaluation

- Physical examination assessing joint hypermobility using the Beighton score.

- Skin extensibility and fragility testing.

- Medical history of joint dislocations, chronic pain, and cardiovascular issues.

2. Genetic Testing

- Confirms diagnosis for most EDS subtypes (except hEDS).

- Helps identify inheritance patterns and provide genetic counseling.

3. Imaging and Additional Tests

- Echocardiograms to assess heart valve or aortic abnormalities.

- MRI or CT scans to evaluate vascular integrity in vEDS.

- Ophthalmologic exams for corneal complications.

Treatment and Management

Currently, there is no cure for EDS. Management focuses on symptom relief, prevention of complications, and improving quality of life.

Physical Therapy

- Strengthening muscles to stabilize joints.

- Low-impact exercises like swimming and Pilates.

- Avoiding high-impact sports that increase injury risk.

Pain Management

- Medications: NSAIDs, acetaminophen, or stronger pain relievers.

- Neuropathic pain medications (gabapentin, duloxetine).

- Non-drug approaches: heat therapy, massage, acupuncture.

Cardiovascular Care

- Regular cardiovascular monitoring (especially in vEDS).

- Beta-blockers may be prescribed to reduce vascular stress.

- Emergency plans for vascular rupture events.

Surgical Considerations

- Surgery is challenging due to tissue fragility and poor wound healing.

- Surgeons require special precautions when operating on EDS patients.

Lifestyle Modifications

- Ergonomic tools to minimize strain.

- Joint braces or supports.

- Diet tailored to reduce gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Adequate rest and pacing to manage fatigue.

Psychological Support

- Living with a chronic illness often results in depression, anxiety, or social isolation.

- Therapy and support groups are highly beneficial.

Prognosis

The outlook for individuals with EDS depends on the subtype:

- Hypermobile and classical types: Chronic but manageable, with proper care allowing for near-normal life expectancy.

- Vascular EDS: Reduced life expectancy due to risk of arterial rupture; median survival is estimated at 48–50 years, though some patients live longer with close medical supervision.

- Rare subtypes: Prognosis varies significantly.

Living with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Patients with EDS often face invisible challenges, such as chronic pain, fatigue, and mobility limitations, which are not immediately apparent to others. Misdiagnosis is common, with many patients initially told they have fibromyalgia, anxiety disorders, or psychosomatic illnesses before receiving a proper diagnosis.

Daily life may require adaptations:

- Using mobility aids.

- Wearing compression garments for blood circulation.

- Avoiding overexertion.

- Navigating frequent medical appointments.

Community support, patient advocacy groups, and educational resources play an important role in improving quality of life.

Research and Future Directions

Exciting progress is being made in EDS research:

- Genetic discoveries may soon reveal the cause of hEDS.

- Collagen-targeted therapies are under investigation.

- Gene editing technologies like CRISPR could eventually provide corrective treatments.

- Multidisciplinary clinics dedicated to connective tissue disorders are improving diagnosis and coordinated care.

Conclusion

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is a multifaceted disorder that challenges patients, families, and healthcare providers alike. Although incurable, advances in genetics, medicine, and supportive care continue to improve outcomes. Greater awareness and education are essential—not just for early diagnosis but also for reducing the stigma that patients often face when their symptoms are dismissed or misunderstood.

Living with EDS requires resilience, adaptation, and strong support networks, but with proper care, many individuals lead fulfilling lives despite the condition’s challenges. Continued research offers hope for more targeted therapies and, perhaps in the future, curative options.

References

- Malfait, F., Francomano, C., Byers, P., et al. (2017). The 2017 International Classification of the Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C: Seminars in Medical Genetics, 175(1), 8–26.

- Bowen, J. M., Sobey, G. J., Burrows, N. P., et al. (2017). Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, classical type. GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle.

- Byers, P. H., Belmont, J., Black, J., et al. (2017). Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. GeneReviews® [Internet]. University of Washington, Seattle.

- Tinkle, B., Castori, M., Berglund, B., et al. (2017). Hypermobile Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome (a.k.a. Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome Type III and Ehlers–Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility Type): Clinical Description and Natural History. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C, 175(1), 48–69.

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society. (2023). EDS and HSD Classification and Diagnosis.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) – Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). (2024). Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Overview.

- Beighton, P., De Paepe, A., Steinmann, B., Tsipouras, P., Wenstrup, R. J. (1998). Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: Revised nosology, Villefranche, 1997. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 77(1), 31–37.

- Callewaert, B., Malfait, F., Loeys, B., De Paepe, A. (2008). Ehlers–Danlos syndromes and Marfan syndrome. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology, 22(1), 165–189.

- Pyeritz, R. E. (2019). Ehlers–Danlos syndromes: 2020 update. Genetics in Medicine, 21(4), 674–687.

- Demmler, J. C., Atkinson, M. D., Reinhold, E. J., Choy, E., Lyons, R. A., Brophy, S. T. (2019). Diagnosed prevalence of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and hypermobility spectrum disorder in Wales, UK: A national electronic cohort study and case–control comparison. BMJ Open, 9(11), e031365.