Tooth wear, also known as tooth surface loss (TSL), is a topic that affects almost every adult to some degree. While minor wear is a natural part of aging, excessive or pathological wear can lead to sensitivity, poor aesthetics, difficulty eating, and major restorative problems if left untreated.

In recent years, tooth wear has attracted increasing attention in dentistry. Changing diets, stressful lifestyles, increased consumption of acidic foods and drinks, and rising levels of bruxism mean more patients are experiencing tooth wear earlier — sometimes even in their 20s or 30s.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat Is Tooth Wear?

Tooth wear is defined as the irreversible loss of tooth tissue—enamel, dentine, or both—caused by processes other than dental caries (decay) or trauma.

Unlike cavities, which result from bacteria metabolizing sugars, tooth wear results mainly from mechanical or chemical factors. Importantly:

- Some wear is normal as we age.

- Excessive wear becomes pathological, especially when it leads to pain, sensitivity, structural problems, or cosmetic concerns.

- What seems normal in a 70-year-old might be alarming in a 20-year-old.

Thus, understanding both the amount and the rate of wear is crucial.

Why Tooth Wear Matters

Tooth wear is much more than a cosmetic problem. Over time, it can lead to:

- Hypersensitivity

- Cracking of weakened enamel

- Loss of tooth height and changes in the bite

- Problems chewing

- Increased likelihood of needing crowns or root canal treatment

- Loss of confidence due to changes in smile appearance

- In severe cases, the need for complex, expensive restorative work

The Adult Dental Health Survey (UK, 2009) found that:

- 77% of adults had at least one tooth worn to dentine

- By age 75, around 40% have moderate tooth wear

- Severe wear affects a smaller but significant minority

These statistics underline how essential early detection and prevention are.

Types of Tooth Wear: The Four Major Categories

Tooth wear is not a single process. Rather, it typically results from several overlapping mechanisms. Clinicians separate tooth wear into four main types to help understand, diagnose, and treat it effectively.

1. Erosion — Tooth Loss from Acid

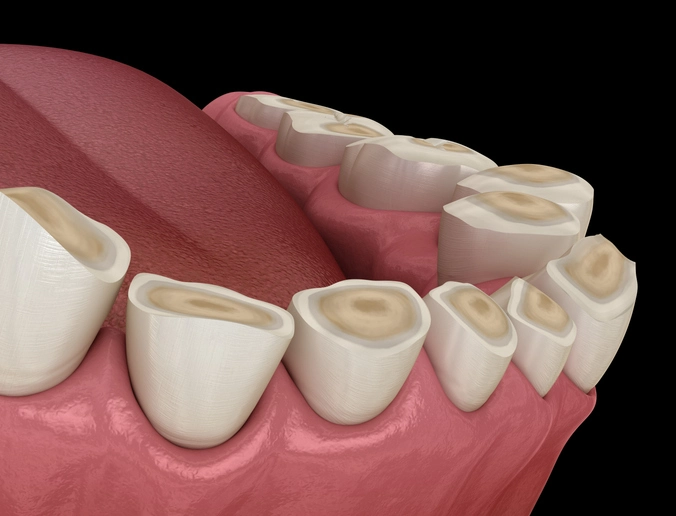

Erosion is the chemical dissolution of tooth structure by acid not involving bacteria. Acids soften and dissolve enamel, making it progressively smoother, shinier, and eventually thin enough that dentine becomes exposed.

Once dentine is uncovered, wear progresses more rapidly — dentine is 5 times softer than enamel and more prone to wear.

What erosion looks like

- Smooth, shiny surfaces

- “Cup-shaped” depressions on occlusal and incisal surfaces

- Broad, shallow defects

- Restorations such as amalgam appear “proud” because tooth structure around them dissolves

- Increased sensitivity

Sources of erosive acids

Erosion can be intrinsic (from inside the body) or extrinsic (from diet or environment).

A. Intrinsic Erosion

Intrinsic acids come from the stomach. Key causes include:

- Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD/GERD)

- Frequent vomiting (pregnancy sickness, gastrointestinal disorders)

- Eating disorders such as anorexia or bulimia

- Chronic stress-induced rumination

This type typically affects the palatal surfaces of upper anterior teeth and the occlusal/buccal surfaces of lower molars, which are most exposed to stomach acid during reflux or vomiting.

These conditions often require medical or psychiatric referral, as dental treatment alone will not stop the acid exposure.

B. Extrinsic Erosion

External acids are a major contributor to tooth wear in modern lifestyles.

Common sources include:

Dietary acids

- Carbonated soft drinks and energy drinks

- Fruit juices, particularly citrus

- Vinegar-containing foods

- Pickles and flavored waters

- Sports drinks

The labial (front) surfaces of upper incisors are classically involved.

Environmental acids

Historically found in:

- Battery factories

- Metal processing

- Industrial chemical exposure

Now rare due to safety regulations.

Competitive swimmers may also be at risk if pool water is imbalanced.

Medication

Some medicines have low pH values, including:

- Vitamin C tablets

- Iron tonics

- Acidic saliva stimulants

- Nutritional supplements

2. Attrition — Tooth-to-Tooth Wear

Attrition is the mechanical wear caused by direct contact between teeth.

This can be a normal process; however, it increases dramatically in:

- Patients with bruxism (clenching or grinding)

- Individuals who consume highly abrasive foods

- Patients with an edge-to-edge bite

Clinical signs

- Matching wear facets on opposing teeth

- Flattened occlusal surfaces

- Fractured cusps in severe cases

- Often combined with erosion (acid-softened teeth wear faster)

Bruxism is strongly linked to stress, sleep disorders, and certain medications, and often occurs subconsciously at night.

3. Abrasion — Wear Caused by Objects

Abrasion occurs when tooth tissue is worn away by physical contact with external objects, such as:

- Over-aggressive toothbrushing

- Abrasive toothpastes

- Nail-biting

- Pipe smoking

- Habitual use of hairpins, pens, etc.

Typical features include:

- V-shaped or dished-out cervical lesions

- Notches on the enamel near the gum line

- Localized wear corresponding to the source of mechanical force

This type of wear can accelerate dramatically if erosion is also present, as softened enamel abrades more easily.

4. Abfraction — Stress-Induced Microfracturing

Abfraction is a controversial but widely discussed concept. It describes:

Cervical tooth tissue loss due to stress concentration from clenching or occlusal overload.

The hypothesis suggests that flexing of the tooth under heavy loads causes microcracks at the neck of the tooth, eventually forming V-shaped lesions.

Although debated, many clinicians encounter lesions that cannot be fully explained by erosion or abrasion alone.

Diagnosing Tooth Wear

Diagnosis requires a thorough, holistic approach. Tooth wear often has multiple causes, and many may no longer be active by the time the patient presents. A detailed:

- History

- Clinical examination

- Special investigations

…are essential to determine both the aetiology and the rate of progression.

Key questions to ask

- Dietary habits — frequency of acidic drinks?

- Medical history — reflux? vomiting? medications?

- Stress levels — bruxism? clenching?

- Oral hygiene habits — brushing technique? toothpaste type?

- Lifestyle factors — swimming? occupational exposure?

- Past eating disorders or pregnancy sickness (approached sensitively)

Patients may be unaware of behaviours like nighttime bruxism, so collateral information (partner reports, headaches, jaw ache) may help.

Indicators of ongoing wear

To determine whether wear is active or historic, clinicians look for:

- Fresh, bright, unstained dentine (active)

- Stained defects (older lesions)

- Increasing sensitivity

- Progressive changes in photographs or casts over time

Tools such as study models, photographs, and silicone indices play a vital role in monitoring.

Measuring Tooth Wear: The BEWE Index

The Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE) is a widely used screening tool for quantifying erosive wear.

In the BEWE system:

- The most affected surface in each sextant is scored from 0 to 3.

- The total score is used to determine risk level and management.

BEWE Score Guide

- 0 — No visible wear

- 1 — Initial loss of surface texture

- 2 — Hard tissue loss <50% of surface area

- 3 — Hard tissue loss ≥50% of surface area

The BEWE is not ideal for monitoring subtle progression, but it is excellent for risk assessment, treatment planning, and patient education.

Management of Tooth Wear

Management focuses on three major pillars:

- Removing or reducing aetiological factors

- Preventing further damage

- Repairing or restoring tooth structure when necessary

Because tooth wear is multifactorial, treatment must be individualized.

Prevention: The Foundation of Treatment

A. Behavioural and lifestyle modifications

Patients may need to adjust:

- Diet (limit acidic drinks, sip through a straw, avoid sipping over long periods)

- Brushing habits (softer brush, avoid brushing immediately after acidic foods/drinks)

- Habits such as nail-biting or pen-chewing

- Stress-related behaviours like clenching

B. Medical or specialist referral

Some conditions require co-management:

- GERD → gastroenterologist

- Eating disorders → psychiatrist/psychologist

- Bulimia → multidisciplinary team

- Severe bruxism → sleep specialist

C. Tooth protection

- High-fluoride toothpaste or varnish

- Mouthguards for bruxism

- Remineralizing agents like CPP-ACP or fluoride supplements

Monitoring

For patients with mild or questionable wear, regular monitoring may be the appropriate initial approach. Documentation should include:

- Photographs

- Impressions or digital scans

- Wear indices

- Bitewing radiographs when indicated

Monitoring helps determine whether active intervention is required.

When to Intervene: Indications for Restorative Treatment

Intervention is indicated when wear causes:

- Sensitivity that affects quality of life

- Poor aesthetics

- Functional issues (loss of vertical dimension, difficulty chewing)

- Progressive structural weakening

Restorative Options

A. Minimally invasive treatments

- Composite bonding

- Glass ionomer (less aesthetic, but great for cervical lesions)

- Palatal veneers for upper incisors

- Protective overlays

These options help reduce sensitivity, improve appearance, and restore lost tooth structure without major drilling.

B. Managing loss of vertical dimension (OVD)

In severe wear cases, patients may require an increase in occlusal vertical dimension. The Dahl concept is commonly used:

- Composite is placed on palatal surfaces of anterior teeth.

- Posterior teeth temporarily disclude (do not touch).

- Over 3–6 months, posterior teeth erupt and/or anterior teeth intrude.

- A new stable occlusion is achieved, creating space for restoration.

This approach avoids aggressive crown preparation but becomes less predictable with age.

C. When over-eruption complicates aesthetics

If teeth have erupted excessively to compensate for wear, it may be impossible to create a pleasing smile without:

- Increasing OVD

- Surgically lengthening crowns to create space

- Orthodontic intrusion

These more invasive procedures are reserved for complex restorative cases.

D. Full-coverage restorations

Crowns or onlays may be required in:

- Extensive wear

- Teeth with little remaining structure

- Cases where bonded composites are unlikely to survive

However, because tooth wear patients often have thin, fragile enamel, conservative preparation is essential.

E. Overdentures

At the extreme end, when teeth are severely worn and structurally compromised, overdentures may be the most feasible option. While they can restore function, they are generally less aesthetic.

Managing Sensitivity

Sensitivity affects 9–12% of patients with tooth wear.

Management options include:

- High-fluoride toothpaste

- Desensitizing agents

- Composite or GI restorations

- Covering exposed dentine

- Root canal treatment (for cases with pulpal exposure)

Prompt management helps prevent chronic pain and protects the pulp.

The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Prevention

Tooth wear is often silent in its early stages. Patients may only notice it when:

- Teeth look shorter

- Edges chip easily

- Sensitivity suddenly appears

- Fillings seem to “stand up” from the tooth surface

By this stage, significant structural loss may already have occurred.

Early diagnosis enables dentists to:

- Identify risk factors

- Prevent further deterioration

- Educate patients

- Restore minimally where needed

- Avoid future extensive, costly dental work

Conclusion

Tooth wear and tooth surface loss are increasingly common issues in modern dentistry. While some wear is inevitable with age, excessive or pathological wear presents real challenges in aesthetics, comfort, and long-term oral health.

Understanding the four types of wear—erosion, attrition, abrasion, and abfraction—helps clinicians diagnose underlying causes and create personalized treatment plans. Management often includes a combination of behavioural modification, prevention, monitoring, and restorative procedures, depending on the severity and progression of the wear.

Ultimately, early detection and patient education are the cornerstones of protecting teeth from irreversible damage. By recognizing risk factors early and modifying destructive habits, patients can maintain healthy tooth structure and avoid complex restorative work later in life.

References

- Bartlett, D. et al. (2008) Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE). Clinical Oral Investigations, 12(Suppl 1), pp. 65–68.

- Bartlett, D.W. & Shah, P. (2006) A critical review of non-carious cervical (wear) lesions and the role of abfraction, erosion, and abrasion. Journal of Dental Research, 85(4), pp. 306–312.

- Gulamalai, A.B. et al. (2011) Management of severe tooth wear using the Dahl concept: A case series. British Dental Journal, 211, E9.

- Lussi, A. & Jaeggi, T. (2008) Erosion—Diagnosis and risk factors. Clinical Oral Investigations, 12(Suppl 1), pp. 5–13.

- Rees, J.S. et al. (2011) The prevalence of tooth wear in the UK adult population. Dental Update, 38, pp. 24–32.

- Simswathumaraperuma, K. et al. (2012) Prevalence of severe tooth wear and the association with erosive factors in adults. Journal of Dentistry, 40(6), pp. 457–463.

- Smith, B.G.N. & Knight, J.K. (1984) A comparison of tooth wear indices. Journal of Periodontology, 55(4), pp. 265–271.

- World Health Organization (2012) Oral health surveys—Basic methods. 5th ed. Geneva: WHO Press.

- Addy, M. & Shellis, R. (2006) Interaction between attrition, abrasion, and erosion in tooth wear. Monographs in Oral Science, 20, pp. 17–31.

- Grippo, J.O. (1991) Abfraction: A new classification of hard tissue lesions of teeth. Journal of Esthetic Dentistry, 3(1), pp. 14–19.

- Lambrechts, P. & van Meerbeek, B. (1997) Understanding the pathology of tooth wear. Quintessence International, 28(10), pp. 689–695.

- Tea, R. & Watson, T. (2015) Management of erosive tooth wear: A review. Primary Dental Journal, 4(1), pp. 32–37.