If you’ve ever heard an orthodontist mention a “Frankel appliance” or “functional regulator,” they’re referring to a removable device that doesn’t look or work like a typical retainer. Rather than pushing teeth around directly, the Frankel appliance (often abbreviated FR) trains the muscles of the lips and cheeks, reshapes habits, and creates space so jaws and teeth can develop more harmoniously as a child grows. It’s a different philosophy of orthodontics, one that treats the soft tissue environment as the driver of skeletal and dental change.

This article unpacks what the Frankel appliance is, how it works, who it helps, what it’s like to wear one, how it compares with other functional appliances, and what the evidence actually says about results. It’s written to be useful whether you’re a curious parent, a patient, or a dental professional looking for a crisp, research-anchored overview.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is a Frankel appliance?

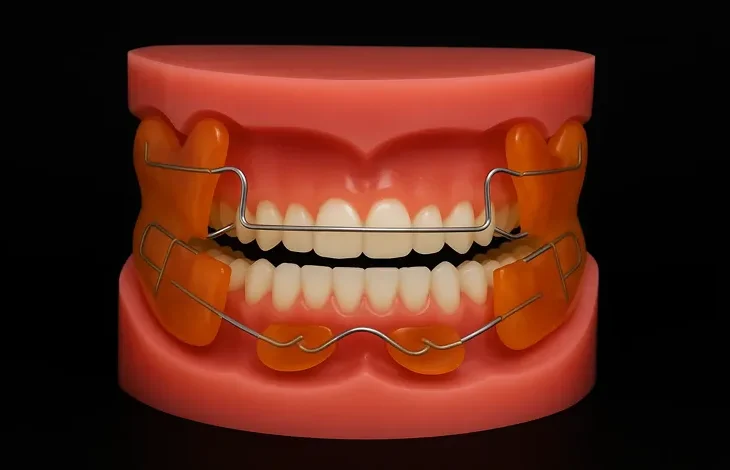

The Frankel appliance, also called the Frankel Functional Regulator (FR), is a removable, tissue-borne orthodontic appliance developed by the German orthodontist Rolf Fränkel in the mid-20th century. Unlike tooth-borne appliances that clasp and leverage teeth, the Frankel sits primarily in the buccal and labial vestibules (the spaces between the cheeks/lips and the teeth). Its acrylic vestibular shields and lip pads block overactive cheek and lip pressure, encourage healthier muscle patterns, and allow the dental arches and jaws to grow toward a more favourable relationship.

A quick historical note. Rolf Fränkel (1908–2001) introduced his “functional regulator” approach publicly in 1966, building on the idea that the orofacial musculature (and the “functional spaces” it creates) influences skeletal development—a view aligned with Melvin Moss’s functional matrix theory. His work was initially published in German and later amplified in English-language journals through collaborators such as James A. McNamara, which helped the concept spread globally.

How the Frankel works: training the soft tissues to help the skeleton

At first glance the FR looks bulky. That bulk is intentional: acrylic shields rest in the cheeks and lips to reduce abnormal muscle pressure on the dental arches. Stainless-steel support wires and occlusal rests stabilise the appliance but are not used to “pull” teeth in the way fixed braces do. By freeing the arches from constricting soft-tissue forces, the appliance lets the jaws and teeth erupt and grow following the patient’s genetics and functional use—ideally toward a wider, more stable arch form and an improved jaw relationship.

Key biomechanical/biological ideas behind the FR:

- Vestibular (buccal) shields: acrylic flanges that sit in the cheeks to stop the buccinator complex from squeezing the maxillary and mandibular arches inward. This can encourage transverse arch development.

- Lip pads: acrylic pads (often lower) that rest in front of the incisors to deactivate a hyperactive mentalis and help train a competent lip seal. This can reduce lower incisor proclination driven by a hypermentalis habit.

- Occlusal rests/support wires: passively stabilise the device and can influence eruption (e.g., limiting upper first molar eruption if desired), while the bulk of action remains neuromuscular rather than tooth-borne.

With Class III patterns due in part to maxillary deficiency, a variant (FR-3) uses upper labial pads to remove restraining lip pressure on the maxilla, allowing forward growth or anterior bone apposition. The exact biologic mechanism has been studied and discussed; clinically, the goal is to relieve soft-tissue constraints so the maxilla can express growth potential.

For skeletal anterior open bite, the FR-4 adapts vestibular shields and labial pads with a regimen that emphasises lip seal training and vertical control; studies have reported favourable changes such as upward/forward mandibular rotation and improved incisor display when used during growth.

Main Frankel types (FR-1 to FR-4) and when they’re used

Although clinicians individualise every appliance, classic Frankel appliances are grouped as FR-1 through FR-4:

- FR-1: Used primarily in crowded Class I and Class II Division 1 cases during the mixed dentition, especially when the goal is to develop the arch form while reducing perioral muscular constriction. It is often introduced when incisors have erupted and primary molars remain for retention.

- FR-2: The most commonly used Frankel in many practices for Class II problems (especially mandibular retrusion), with emphasis on neuromuscular re-education (e.g., deactivating mentalis) and arch development during growth.

- FR-3: For Class III cases with maxillary retrusion, employing upper labial pads and vestibular shields to diminish restrictive lip pressure on the maxilla. Best timed to early mixed dentition when growth modification is most responsive.

- FR-4: For skeletal anterior open bite patterns; aims to restore lip competence and control vertical dimension with documented improvements after ~2 years of wear in growing patients.

Note: You’ll sometimes see sub-variants (e.g., FR-1a, -1b, -1c) tailored to specific bite depths or overjet sizes. The spirit is the same—match shield and pad design to the patient’s pattern and growth potential—while the literature anchors the broader FR-1 to FR-4 indications above.

What it’s like to wear a Frankel

Daily wear & schedule. Frankel appliances are removable. Typical protocols ask for after-school/evening and overnight wear (often 14–16 hours/day), plus exercises for lips and tongue posture that the clinician prescribes. Longer continuous wear—especially during quiet activities like reading or homework—helps the orofacial muscles learn new, healthier “default” positions.

Speech & drooling. In the first 1–2 weeks, expect more saliva and some lisping. As muscles adapt, these effects usually diminish. Consistent wear is the fastest route to normal speech with the appliance in.

Eating & sports. Because it’s removable, the FR comes out for meals, toothbrushing, and contact sports. Store it in a ventilated case when not worn. (Your clinician will set exact rules based on your case.)

Hygiene. Rinse after each wear period and brush the acrylic gently once daily with a soft brush and mild soap (not toothpaste, which can scratch acrylic). Keep it away from heat sources.

Adjustments & reviews. Expect periodic appointments for checks and minor adjustments to pads, shields, and wires. Because forces are largely from soft-tissue modulation rather than active screws or springs, many visits are about behavioural coaching (lip seal practice, posture reminders) and ensuring the appliance still fits the growing face as intended.

Step-by-step: from records to construction to delivery (the clinician’s view)

- Records and diagnosis. Photos, study models or scans, cephalometrics, and a full functional exam (lip competence, mentalis activity, tongue posture, nasal airway) determine whether the Frankel philosophy fits the pattern.

- Construction bite. The clinician registers a bite that positions the mandible in a therapeutically favourable posture while preserving airway and comfort. The anterior region is typically kept open to assess midlines and overjet during setup.

- Laboratory fabrication. Using the models, the lab constructs the acrylic vestibular shields and lip pads, plus stabilising wires and occlusal rests. There’s a long tradition of detailed, stepwise guidance for FR-2 and FR-3 fabrication in the literature (e.g., McNamara and colleagues), which labs follow to achieve predictable fit.

- Insertion and coaching. At delivery, clinicians emphasise lip-seal exercises, nasal breathing, and mentalis relaxation, often demonstrating how the lower lip should rest without strain against the lip pads. Early behavioural change is a major predictor of success.

- Follow-up and growth monitoring. Appointments track arch dimensions, overjet/overbite, molar relationships, and—crucially—soft-tissue posture at rest and during function. Adjustments are made as the patient grows.

How the Frankel compares with other functional appliances

Twin Block (removable, tooth-borne), Bionator/Activator (removable), and Herbst (fixed) are the best-known alternatives for Class II problems. All aim to improve the sagittal jaw relationship during growth, but they differ in force delivery and compliance needs.

- Frankel vs Twin Block/Activator/Bionator. Twin Block and Activator rely more on tooth-borne bite blocks or acrylic plates to posture the mandible forward; the Frankel relies more on soft-tissue shields and muscle re-patterning. Comparative studies suggest that while appliance designs differ, the net skeletal effects during growth are generally modest and similar in magnitude, with much of the occlusal improvement due to dentoalveolar change and growth redirection.

- Frankel vs Herbst. The Herbst is fixed (no compliance with wear) and tends to produce quicker sagittal correction with a stronger dentoalveolar component. In matched samples, both can correct Class II relationships; choice often balances patient compliance, desired biomechanics, and side-effect profiles.

Bottom line: The Frankel’s unique value is its tissue-borne, habit-focused approach—attractive when clinicians feel that mentalis overactivity, poor lip seal, or buccinator pressure are key drivers of the malocclusion. When compliance is uncertain or rapid dentoalveolar correction is the priority, a fixed option (e.g., Herbst) may be preferred.

What the evidence says (in plain English)

Orthodontics benefits from an expanding pool of clinical trials and systematic reviews. A few takeaways relevant to Frankel-type therapy:

- For Class II in growing patients, functional appliances work—but the effect size on mandibular growth is modest. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews (pooling removable and fixed functionals) consistently find short-term skeletal effects on the order of 1–2 mm of additional mandibular length versus controls, alongside larger dentoalveolar contributions and favourable overjet/ANB changes. Clinically meaningful? Often yes—particularly when combined with the patient’s remaining growth—but it’s not jaw “reshaping” in the dramatic sense.

- Timing matters. Starting during the pubertal growth spurt tends to amplify effects (this principle applies across functionals, including FR). The large Cochrane review on Class II treatment highlights that functional appliances reduce excessive overjet compared with no treatment during adolescence, while differences among specific appliances are small.

- Early two-phase care can reduce incisor trauma risk. In children with prominent upper incisors, providing early functional treatment (phase I) reduces the incidence of incisal trauma compared with waiting for one course in adolescence—a meaningful public-health outcome for kids at risk.

- Appliance-specific evidence. There are device-focused studies—e.g., FR-3 protocols for Class III maxillary deficiency and FR-4 for anterior open bite—reporting positive skeletal and soft-tissue changes during growth. These are often cohort or clinical trials rather than large RCTs, so clinicians integrate them with broader functional-appliance evidence and growth considerations.

Evidence-based expectation setting: A Frankel can meaningfully improve overjet, arch form, soft-tissue balance, and the occlusal relationship, especially when introduced at the right time and worn as prescribed. Skeletal changes occur, but they’re incremental and ride on the back of the child’s natural growth.

Advantages and limitations at a glance

Potential advantages

- Targets the cause, not just the symptom. If overactive lips/cheeks and poor posture are major drivers of a narrow arch or deep overjet, the FR’s muscle re-education can be especially effective.

- Fosters transverse arch development by removing cheek pressure, which may reduce the need for some expansion mechanics in select cases.

- Removable and tooth-friendly. With minimal direct forces on the teeth, there may be fewer unwanted dental side effects compared with some tooth-borne appliances, depending on the setup. (This is case-specific.)

Limitations

- Bulky and compliance-dependent. The biggest practical challenge is wear time. If a patient won’t wear it, it won’t work. Early lisping and drooling can deter some children without strong coaching.

- Skeletal changes are real but moderate. Like other functionals, the FR won’t “grow a new jaw,” and unrealistic expectations can lead to disappointment.

- Case selection is everything. Severe crowding requiring extractions, very high vertical patterns without control, or airway issues may shift a clinician toward other protocols or a staged plan. (This reflects common clinical reasoning; specific decisions are individualised.)

Indications, age, and timing

- Ideal candidates include growing patients with Class II due mainly to mandibular retrusion (FR-2), Class III due to maxillary deficiency (FR-3), skeletal anterior open bite with poor lip seal/hypermentalis (FR-4), and crowded Class I patterns where arch development and soft-tissue training are appropriate (FR-1).

- Timing typically falls in mixed dentition through early adolescence. Class III FR-3 and open-bite FR-4 protocols often begin earlier to capture maxillary and vertical growth windows.

- Duration varies with goals and growth but commonly ranges from 12–24 months, followed by retention (which may be a conventional retainer or continuing limited wear as habits stabilise). Exact timelines are case-specific and guided by growth status.

A week-by-week feel for adaptation (for families)

- Week 1: More saliva, a lisp, and cheek/lip awareness are normal. Practise speaking aloud with the appliance (read a page or two nightly).

- Weeks 2–4: Speech improves; drooling settles; lip-seal exercises get easier. Parents often notice the child’s lips resting together more comfortably at rest.

- Months 2–4: Clinicians often document better mentalis relaxation and early changes in overjet/arch width, depending on the case and wear consistency.

- 6 months and beyond: If wear is good, you’ll see the trajectory: softer lip strain, gentler smile lines, and continuing occlusal improvement. Adjustments keep pace with growth.

Practical tips to maximise success

- Make wear automatic. Tie wear to routines: after school, homework, reading, and bedtime.

- Use a progress chart for kids. Stickers or a calendar app keeps motivation up.

- Practise lip-seal drills. Your clinician may suggest gentle closed-lip holds while breathing through the nose; do these with the FR in place as instructed.

- Mind the case. If it’s not in your mouth, it’s in the case—never on a lunch tray or in a pocket.

- Report sore spots. Localised rubbing on the vestibules can be adjusted quickly; don’t “tough it out.”

Frequently asked questions

Will a Frankel change my face?

It can influence soft-tissue balance and arch form during growth, sometimes softening lip strain and broadening the smile. Expect incremental skeletal changes that align with your growth potential, not a dramatic reshaping.

If results are modest skeletally, why use it?

Because modest skeletal change plus meaningful dentoalveolar change, habit correction, and better function often add up to a stable, attractive outcome—especially when started at the right time. For kids with large overjets, early functional treatment also reduces incisor trauma risk.

Isn’t a fixed appliance easier?

Fixed options (e.g., Herbst) avoid the compliance trap but come with their own side-effect profiles and goals. If hyperactive lips/cheeks and poor lip seal are central problems, a tissue-borne Frankel directly targets them. Many clinicians use both approaches in different patients—or even in sequence.

Will I still need braces?

Often, yes. The FR improves the jaw relationship, arch form, and habits; fixed appliances later fine-tune tooth alignment and bite detail. That second phase is typically shorter and easier because the foundation is better.

Does it work for adults?

The Frankel philosophy is growth-sensitive, so it’s most effective in children and adolescents. In adults, it can aid posture and soft-tissue balance but won’t modify skeletal relationships the way it can during growth.

Clinical pearls (for colleagues)

- Diagnose the habit you want to extinguish. Hypermentalis? Incompetent lip seal? Buccinator overactivity? Make that habit the target of your pad/shield design and your chairside coaching.

- Leverage occlusal rests thoughtfully. Use them not only to stabilise the device but also to manage eruption where needed (e.g., restrain upper first molars during Class II correction).

- Record-keeping matters. Track soft-tissue posture in photos (rest posture, smile, and three-quarter views) and note mentalis activity at each visit; families love seeing these subtle changes over time.

- Timing for FR-3 and FR-4 should be early enough to influence maxillary and vertical growth, respectively, with close monitoring of airway and nasal breathing.

- Expectations and motivation are the secret sauce. A short “why this works” script for kids (“we’re teaching your cheeks and lips to be team-mates with your teeth”) can transform compliance.

A brief portrait of the inventor

Rolf Fränkel started treating orthodontic patients as early as 1928 and later practiced in Zwickau, in what became East Germany, where he refined his ideas largely in isolation from Western orthodontics for years. His work emphasised that function and muscle environment shape developing bone and dentition—ideas that eventually resonated with many in the English-speaking world after he lectured (notably in the United States) and published in translation. He received several honours late in his career, including the Albert H. Ketcham Award (1995).

Putting it all together

The Frankel appliance represents a soft-tissue-first approach to early orthodontics. By removing abnormal lip and cheek pressures, encouraging a healthy lip seal and nasal breathing, and allowing the arches to express their genetic width and shape, it changes the environment in which teeth erupt and jaws grow. That strategy is particularly compelling for Class II with mandibular retrusion (FR-2), Class III with maxillary deficiency (FR-3), skeletal anterior open bite (FR-4), and crowded Class I patterns (FR-1) in growing patients.

The research base suggests modest skeletal gains layered onto growth, meaningful reductions in overjet, and an evidence-backed reduction in incisor trauma risk when early treatment is used for protrusive incisors. As with all functional therapy, timing and compliance are the biggest levers—and the Frankel’s success hinges on consistent wear and diligent coaching to retrain the orofacial muscles.

If you’re a parent weighing options, the conversation with your orthodontist will likely cover growth timing, habit patterns, wear expectations, and whether a tissue-borne strategy (Frankel) or a tooth-borne/fixed strategy better fits your child’s needs and temperament. There isn’t a single “best” appliance for everyone; there’s the right appliance for a particular patient, at a particular moment in growth, with a clear plan for follow-through.